In the weeks since assuming office, President Donald Trump has elevated several climate change deniers to key positions in his cabinet, including the recently confirmed head of the Environmental Protection Agency, Scott Pruitt; promised to cut non-discretionary spending, which covers money for research, by $54 billion; and taken specific aim at the budgets of federal agencies that study climate change. These moves all add up, criticssay, to an anti-science administration. (Trump does, however, seem to support a vision for NASA that features a heavier focus on deep space exploration.) Some scientists have rebelled in response, working to copy climate change-related government data they believe officials may delete, and planning a March for Science to take place in Washington, D.C., in April.

What’s it like to be a scientist in Congress in these fraught times? To find out, Pacific Standard spoke with congresspeople with doctorates in research-dependent fields. There aren’t many such folks, but the few who exist offer an inside look at the potential for research funding and evidence-based policy in America over the next four years.

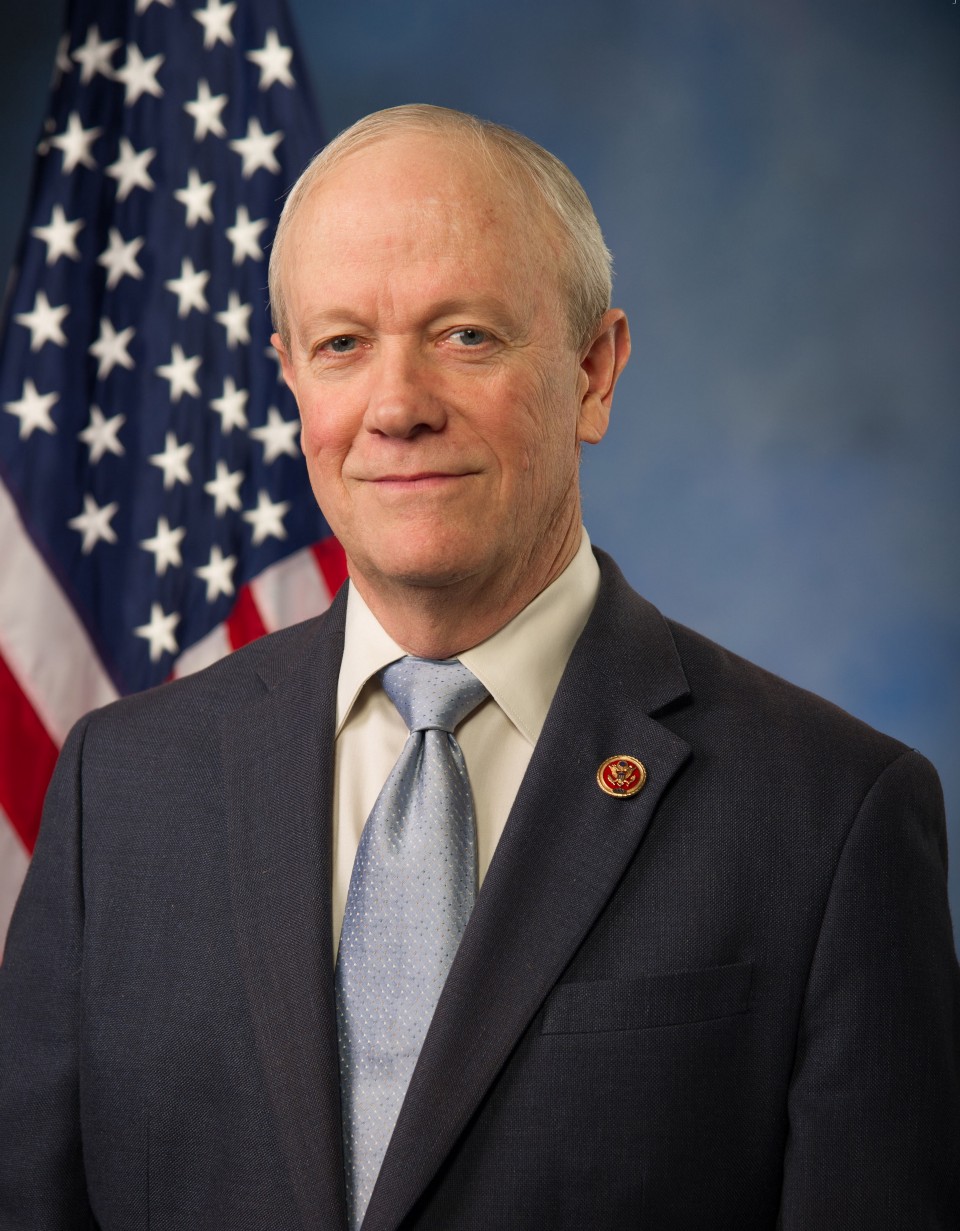

First up, we talked with Representative Jerry McNerney, a Democrat from California, mathematician, and former wind-turbine engineer. He serves on both the Energy and Commerce and Science, Space, and Technology committees.

What’s the feeling in Congress like for science concerns right now?

In the Science committee, things don’t look too rosy in terms of the questions they’re asking and the direction they’re taking the committee, the kinds of hearings that are being proposed.

We had a hearing on the social cost of carbon and they had four witnesses. Three were Republican witnesses, one was a Democratic witness, and the testimony from the Republican witnesses was pretty far off the mainstream. One of them was saying we need to add more carbon into the atmosphere. One of them was saying, “Yeah, the carbon is good because it’s greening up the desert.” The questions that the Republicans were asking were indicating that they don’t think that the science on climate is necessary. It was very discouraging. [Editor’s Note: The “social cost of carbon” is a dollar amount that the EPA calculates to quantify the damage caused by humans emitting a ton of carbon into the atmosphere. The numbers are often used in deciding whether environmental regulations are worth it.]

(Photo: United States Congress)

How do hearings like this translate into policies or laws that citizens might notice?

What happens is you’ll have a hearing like that and then they’ll say, “Well, we don’t need to do that anymore, so we’ll cut funding for that part of the EPA.” They’ll use the testimony and hearing to justify cutting programs.

Is what’s happening now in the Science committee significantly different from how the committee operated in other administrations?

I came in 2007. The Democrats had the majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate, so the Science committee — I was part of it my first term here — was much less partisan. It basically looked at the budgets and how much money we could afford to spend here and there. The chairman really wanted to hear the Republican perspective on things and was cooperating with them on budgetary issues. Now it’s become a very partisan committee. The majority is going to do that they want, without having our input. At least, that’s my opinion.

Since 2011, when the Republicans have had the majority, there’s been a lot of talk about cutting programs in the EPA, in the research that goes into climate change, and so on. But those were merely message bills because we knew the president, no matter what happened in the House, would veto that stuff. Now that we have the president on their side, then these are real proposals, and the president will probably sign them into law if they get past the Senate. So there’s been a change in what actually might happen as a consequence of these discussions.

What does support look like for alternative energy in America?

There’s not much support for alternative energy right now, in terms of the production tax credits, or tax benefits to produce renewable energies. Those are due to expire in the next couple of years. With the current administration and the current majority in the House, I don’t suspect that they will be renewed.

The thing is, wind and solar both becoming cost-competitive now with coal, oil, and natural gas and those fossil-fuel industries are subsidized in different ways, so if you want to really level the playing field, we’re going to need to remove all subsidies. My preference would be to see a carbon tax gradually increasing so that it is predictable and remove all the subsidies for energy production.

Are people in Congress aware of the upcoming March for Science? What do you think of it?

I haven’t heard too many discussions about it, honestly. I think it’s a great idea. I think scientists need to make their presence known and become a part of the American consciousness.

To contrast with the Women’s March, was there a lot of talk about that in Congress before it happened?

There was, yes. That was pretty widely discussed. But that sort of belabors the point, doesn’t it? If Congress is not too aware of the March for Science, then it’s more important than ever that scientists get out there.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.