Is a $15 minimum wage really the answer?

By Dwyer Gunn

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo speaks during a victory rally for a $15 minimum wage on April 4, 2016. (Photo: Kena Betancur/AFP/Getty Images)

One of the tenser moments of last week’s Democratic presidential debate in Brooklyn, New York, came when Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton squared off over the federal minimum wage, an exchange that prompted moderator Wolf Blitzer to remind the candidates that “If you’re both screaming at each other, the viewers won’t be able to hear either of you.” At issue was Clinton’s stance on a $15 federal minimum wage, which Sanders unequivocally supports. While Clinton has expressed support for the $15 minimum wage campaigns being waged in some states and cities, she’s stopped short of backing a $15 federal minimum wage. Clinton instead favors the proposals of Congressional Democrats to gradually increase the federal minimum wage to $12 by 2020.

“I want to get something done,” Clinton said at the debate. “And I think setting the goal to get to $12 is the way to go, encouraging others to get to $15. But, of course, if we have a Democratic Congress, we will go to $15.”

Clinton’s statement sparked some confusion. Sanders pointed out that “I think the secretary has confused a lot of people.” Both the Washington Post and Slate ran stories trying to make sense of Clinton’s seemingly mystifying answer. The Clinton campaign quickly released a statement reiterating her support for a $12 federal minimum wage, with a higher wage in “places where it makes sense.” On Sunday, in an appearance on ABC’s This Week, Clinton described New York’s minimum wage policy as a model for the rest of the country:

That model is a phased in minimum wage increase to get to $15 in the city and surrounding areas, to get to $12, $12.50 upstate, but to be constantly evaluating the economic conditions so that there is no unintended consequence of lost jobs.

That has been my position. And that is exactly what New York just voted for. And for federal legislation, if it has the same kind of understanding about how we have to phase this in, how we have to evaluate it as we go, if the Congress passes that, of course I would sign it.

Clinton’s position isn’t as catchy or simple as Sanders’, but, from an economic perspective, a tiered minimum wage like the kind both New York and Oregon are experimenting with is sound policy. As I wrote a few months ago, the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage has declined dramatically — today’s minimum-wage worker makes 25 percent less than the minimum-wage workers of 1968. But it doesn’t necessarily follow that every part of the country would benefit from a $15 minimum wage. Different states, and different regions within each state, have vastly different costs of living. Suggesting that $15 an hour, or even $12 an hour, is the appropriate minimum wage for every single part of the country is pretty illogical.

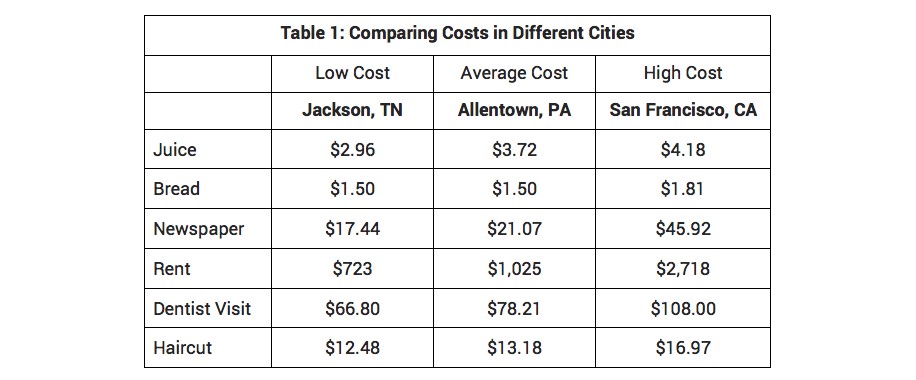

This chart, from center-left think tank Third Way, shows the different prices of a variety of common items across three different metropolitan statistical areas:

(Chart: Third Way)

These differences add up. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage calculator, the “living wage,” defined as “the wage needed to cover basic family expenses plus all relevant taxes,” in Jackson, Tennessee, is $9.63 an hour for one adult. In Washington, D.C., it’s $14.78.

In February, Third Way published an interesting policy proposal to address this issue. The proposal calls for a tiered minimum wage, which would be re-adjusted every three years. The Third Way plan also pushes for metropolitan statistical areas to be grouped into five different tiers based on the cost of living in each area. If the plan were enacted today, areas with the lowest cost of living would have a $9.30/hour federal minimum wage, while the most expensive areas would see an $11.90 federal minimum wage.

From an economic perspective, a tiered minimum wage is sound policy.

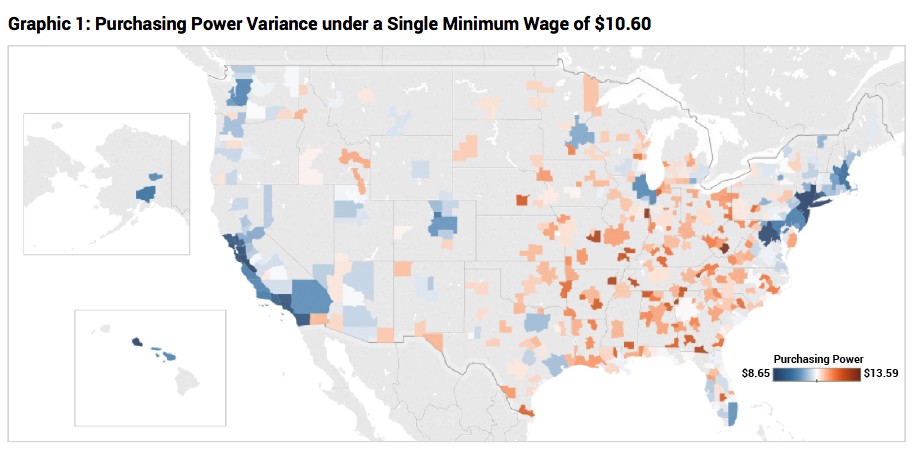

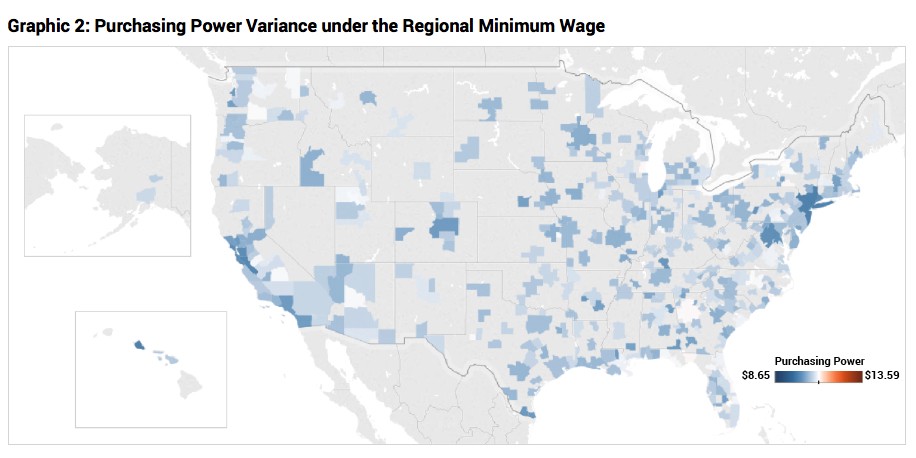

The two maps below, both from Third Way, illustrate the effect of a regional minimum wage. The first shows how the purchasing power of a uniform minimum wage (of $10.60) varies across the country; the second shows how the purchasing power would vary with a tiered regional minimum wage.

(Map: Third Way)

(Map: Third Way)

“This regional wage approach would ensure that all minimum wage workers will have fair basic wages, regardless of where they live, while minimizing reductions in employment and economic distortions in low-cost areas,” Joon Suh wrote in the Third Way proposal. “This policy would ensure that a cashier in Manhattan is essentially earning the same minimum wage in real terms as a cashier in Carbondale, IL and largely addresses fears that a big city minimum wage would destroy jobs in low-cost small towns.”

Minimum-wage increases don’t happen in a vacuum; they have economic consequences. While the evidence suggests that gradual, incremental increases in the minimum wage have, at most, only marginal effects on unemployment, increases that are too steep for the region, or too fast, will almost certainly convince at least some employers to reduce their hiring or replace some workers with technology. “Bernie Sanders suggests that if the minimum wage goes to $15 we may have to pay a few cents more for a hamburger at McDonalds,” Conor Friedersdorf wrote on The Atlantic’s live blog of the debate. “Alternatively, we might go to a McDonalds where we order on an iPad rather than from a cashier, who is laid off and unable to find work as all the other burger chains automate.”

A regional tiered minimum wage may lack the alliterative appeal of the Fight for $15 campaign, but it’s a policy that has a real shot at improving the living standards of poor Americans.

||