A spate of recent articles suggests that Millennials aren’t having “enough” sex—but did anyone ever have the right amount?

By Malcolm Harris

(Photo: MaloMalverde/Flickr)

The American public is mystified by a new youth trend: abstinence. For 25 years now, the age of sexual initiation — i.e. when kids first have sex— has been rising, and fewer teenagers report having had intercourse. With the culture wars over, commentators aren’t lauding Millennials for their responsible choices. Instead, like stereotype jock dads, they’re asking: “What’s wrong with you?”

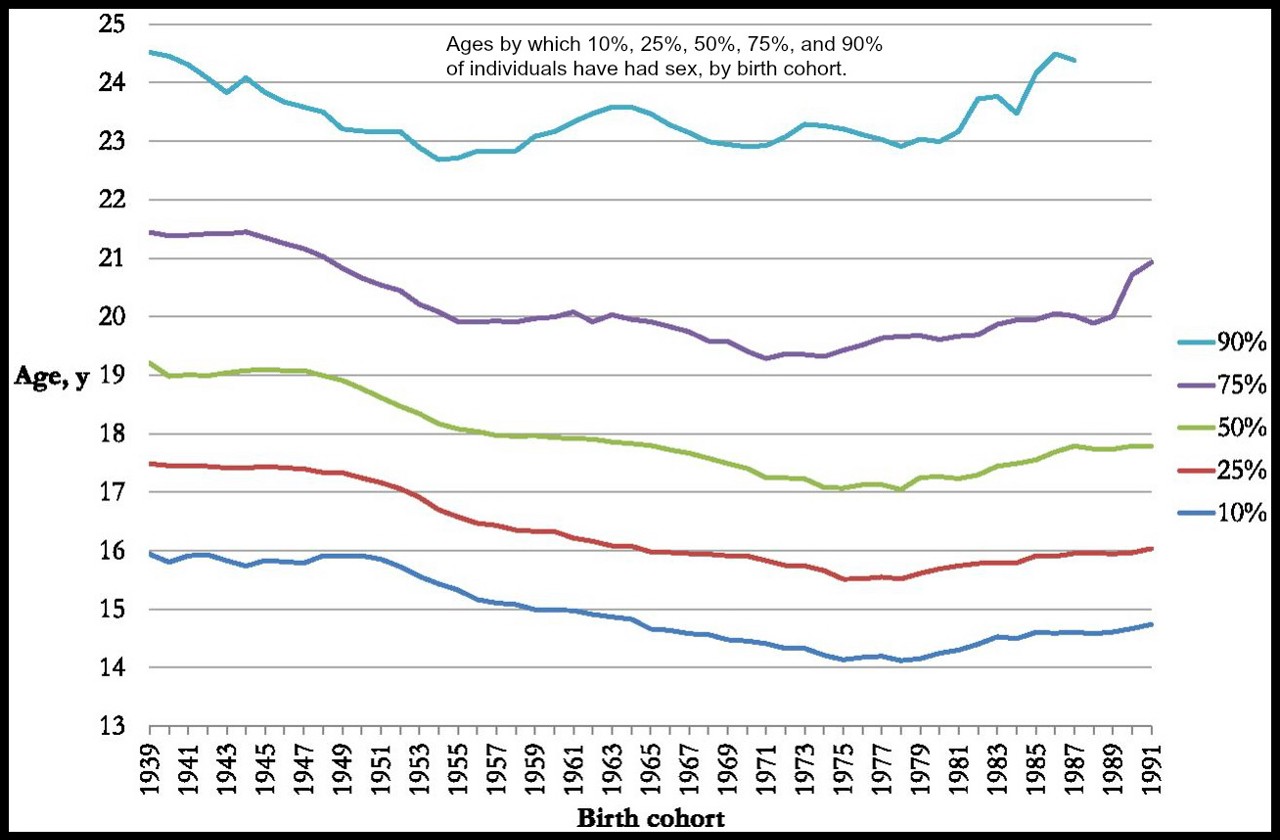

There is no shortage of good explanations. Today’s young people are postponing adulthood. Millennials are medicated and risk-averse or maybe just poor. Every one of these diagnoses seems to hold some validity, but they share a common approach. From the beginning of the 1950s to the end of the ’70s, a child born in America was likely to have sex earlier than a child born the year before. We associate the sexual revolution with the 1960s when it began, but the trend continued until the early ’90s. During that time, we got used to the narrative: As puritanical social norms fade, young Americans will have more sex, which will seem depraved to their parents. But there are problems with casting a 30-year trend as inevitable or natural.

(Chart: Journal of Pediatrics)

Instead of asking why Millennials are having less sex, we could also ask why Boomers and Gen-X had more. Rather than asking why Millennials are so weird, we could compare birth cohorts in a way that doesn’t assume any of them as the baseline. Sexual norms and practices are in constant flux, and we ought not treat them as fixed.

Implicit in the worrying about today’s inexperienced youth is the idea that past generations had the “right” amount of sex, or at least something closer to it. But stripped of the comparison to Millennial abstinence, the sexual revolution’s norms generally fall somewhere between icky and rapey, and a growing list of rock-star obituaries has forced a collective confrontation with America’s recent sexual past. “Once-beloved men are being exposed on what feels like a weekly basis for having taken sexual advantage of less powerful women,” Jia Tolentino wrote after the death of David Bowie. “These incidents are brought to light as exceptions, but they’re beginning to feel like the norm.” I don’t think I’m courting controversy when I say it’s a positive development that it’s no longer considered normal or cool or possibly consensual for powerful men to have sex with 13-year-old girls.

You don’t have to be religious or conservative to take a look at the three decades of sexual revolution and see a more complicated picture than simple human flourishing and joy. No doubt there was some genuinely free love in there, and the breakdown of paternal authority and pseudo-parental social controls on young women’s sexuality were feminist victories hard won — sometimes one household at a time. But gendered power relations didn’t dissolve the way the best hippies hoped they would. Tolentino quotes the essayist Rebecca Solnit about the late 1970s: “The sexual revolution had deteriorated into a sort of free-market free-trade ideology in which all should have access to sex and none should deny access. … There were no grounds. Sex was good; everyone should have it all the time; anything could be construed as consent; and almost nothing meant no, including ‘no.’” Keep in mind that this was only halfway through the period of sexual liberalization.

When iconic ’80s teen movie director John Hughes died in 2009, critics were left to wrestle with the sexual norms in his films. Good girls didn’t have sex unless they were in love, but boys were predators, always seeing what they could get away with in a boys-will-be-rapists way. And if girls got too drunk, then they should have been more careful. Commenting on the end of Sixteen Candles, Amy Benfer writes, “The scene only works because people were stupid about date rape at the time. Even in a randy teen comedy, you would never see two sympathetic male characters conspiring to take advantage of a drunk chick these days.” By the time I was watching teen comedies — like 1999’s 10 Things I Hate About You — guys who pressure or connive girls into sex get punched in the face at the happy end.

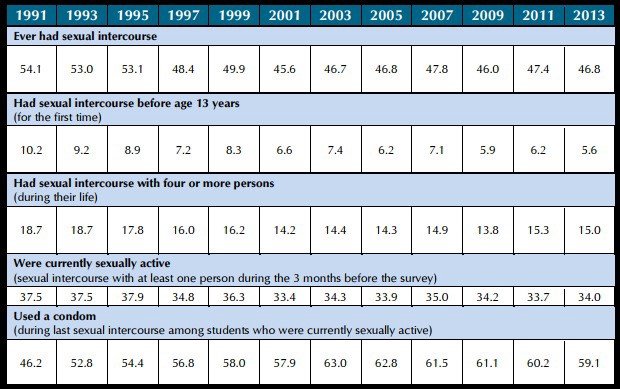

It’s irresponsible to compare generational sexual experience without taking changing standards of consent into account, but that’s also difficult to do right. Rape statistics are notoriously unreliable, and retroactively applying our current norms is impossible. One good measure is in the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which tracks the portion of high schoolers who have intercourse before the age of 13. The phrasing is legally agnostic, but in no American jurisdiction can a 12-year-old consent to sex. Between 1991 — the peak of the sexual revolution — and 2013, this metric declined by a huge degree, from 10.2 to 5.6 percent. Over the same period, the percentage of high-schoolers who reported having had sex declined as well, from 54.1 to 46.8. Condom use, however, increased, from 46.2 to 59.1 percent of sexually active teens.

(Data: YRBS)

How are we to understand these trends? Sexual-health researchers often employ condom use metrics as a proxy measure for gendered power relations — most woman having hetero sex are not trying to get pregnant, and condom use is traditionally a good general indicator of women’s sexual autonomy. One possible explanation based on the data, and on what we know about gender and power in America, is that young women who don’t want to have sex (or aren’t sure) are having their wishes respected at a greater rate. This explanation also fits with the crime data we do have on teen sexual assault victimization, which has declined significantly over the time in question.

There’s another statistic in the YRBS survey data that doesn’t, on its face, seem to conform to the data. Between 1991 (the peak of teen sex) and 2013, the proportion of high-schoolers currently sexually active (defined as having had intercourse within the previous three months) declined only a little, from 37.5 to 34 percent. Therefore, the percentage of teens who stay sexually active after first having sex has actually increased, even though the total has decreased. That seems like a good sign. It also means some of the more-breathless headlines are probably a little misguided.

Teasing out data on such a complicated set of questions is difficult. I’m sure you could come up with an argument that gay marriage has led to teen abstinence, though I don’t know who would be inclined to make it. But when we talk about reasons “Millennials are having less sex,” we don’t usually take time to go into the specifics of American women’s fight for sexual autonomy and freedom from rape over the past hundred years. Looking at teen sex in its proper context prompts us to ask different, better questions about how things used to be, what has changed, and how.

When we compare cohorts in a way that’s not Millennial-centric, it’s clear there was nothing inevitable about the evolution of American sexual norms. There is much work still to be done, but a generation of women who were raised at a time when most didn’t have the right to say “no” changed their culture, and, as a result, their daughters and grand-daughters are growing up in a different kind of society. That is one of the reasons young Americans are having less sex, and it’s an incredible achievement.

||