On April 23rd, 2018, roughly six hours after a 25-year-old man named Alek Minassian rammed a rental van into pedestrians in Toronto, killing 10 people and injuring 15, journalists unearthed a manifesto of sorts. In a cryptic Facebook post uploaded the day of the attack, Minassian declared, “…wishing to speak to Sgt 4chan…. The Incel Rebellion has already begun! … All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!”

Minassian, it seemed, had dedicated his massacre not to a recognizable religious or political agenda, but to 4chan.org, an Internet message board about anime.

To be more precise, he dedicated his massacre to a “joke” on 4chan.

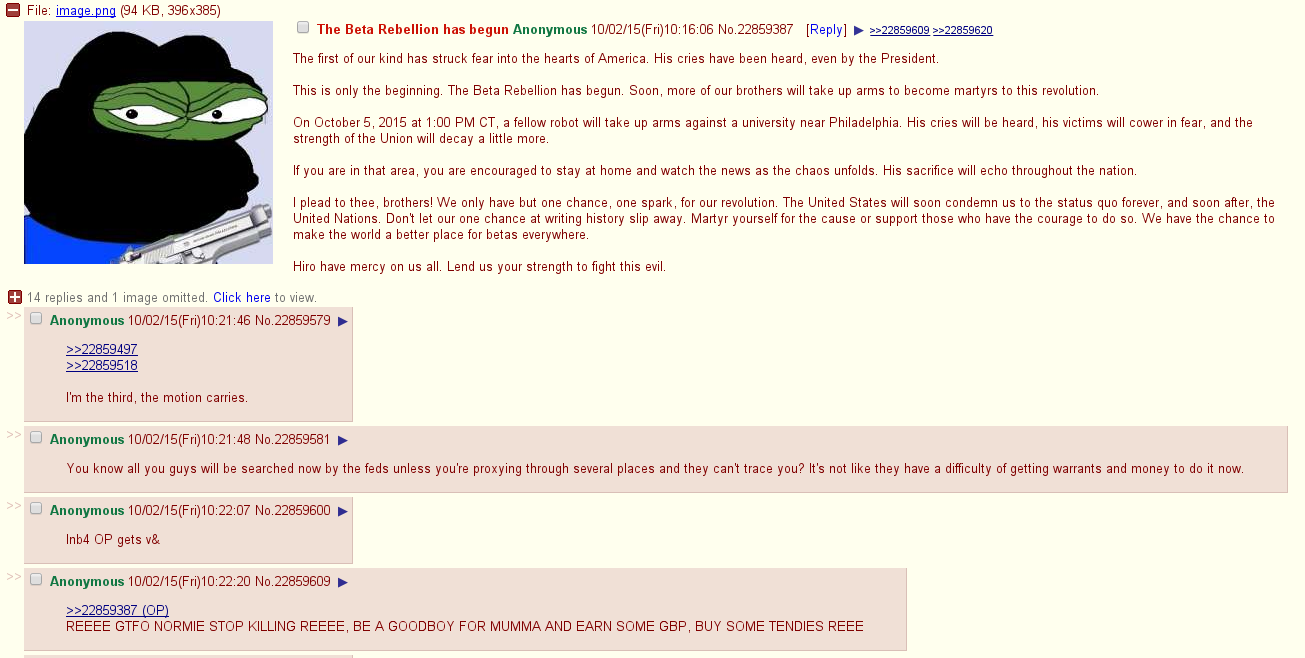

“Incel” is short for “involuntarily celibate,” a term used by young men on the Internet who claim to feel ignored, even berated, by members of the opposite sex. And the “Rebellion” is a reference to a 4chan meme more commonly known as the “Beta Uprising” which imagines self-described loser “beta” males (as opposed to the macho “alphas” of the world) rising up from behind their computer screens in a violent revolution. The “funny” part about this is supposed to be the quixotic nature of the scenario, how it will never become “real.” In other words, betas/incels were making a joke about how they will remain forever trapped in their unhappy circumstances.

The “beta uprising” meme began on a 4chan sub-section called “ROBOT 90001” (/r9k/) in 2014, shortly after a 22-year-old man-boy named Elliot Rodger went on a shooting spree in Isla Vista, California, killing seven people (including himself), and injuring many more.

In a video manifesto uploaded to YouTube before the attack, Rodger explained that, despite being “the supreme gentleman,” he was a “still a virgin” who was taking revenge on women for his lack of sex.

Though the term “beta”—so far as it’s popularly used online—dates from around 2011, the culture had been growing on 4chan since its inception in 2003. By 2014, when Rodger perpetrated his massacre, 4chan’s /r9k/ was merely one node of a network of sites for betas called “the manosphere,” several of which Rodger frequented.

These sites are often rightfully linked to the misogyny that pervades so much of society, laid bare most recently by the #MeToo movement. But why does it seem like toxic masculinity and racism are only growing on the Internet? Why has the manosphere ballooned now of all times?

If we look a little closer, we can, in fact, understand the betas as a product of two very modern forces:

- Decades of increasing inequality and increasingly cutthroat competition for young people to grab even the lowest rungs in society.

- An ever-expanding realm of screen fantasy in cyberspace, video games, film, television, anime, and so forth.

The story of how these elements combined to create a youth culture begins a few decades back.

In the 1980s, Japan had a problem with a so-called “beansprout generation,” kids who, feeling immense pressure to prosper in their careers in a post-war meritocracy, finally lost their sense of optimism and spirit altogether. By the ’90s, many of the beansprouts had dropped out of life. Instead of achieving a career, they threw themselves into a burgeoning world of post-war consumerism as “otaku” (super fans) or “hikikomori” (withdrawn insiders). Rarely leaving their apartments, they instead immersed themselves in new fantasy worlds of anime, manga, and cyberspace. Online, the otaku community eventually coalesced around a bulletin board called, “2channel,” created by Japanese college student in Arkansas named Hiroyuki Nishimura.

(Photo: Niklas Hallen/AFP/Getty Images)

In 2003, a 15-year-old kid in Westchester New York named Christopher Poole thought it might be funny to make an English-language board in the style of 2channel. He called it 4chan. And for the next decade, it filled with Western otaku and other teens and young adults celebrating nihilistic accumulation and escapism. By 2011, 4chan was one of the most popular websites on the Internet.

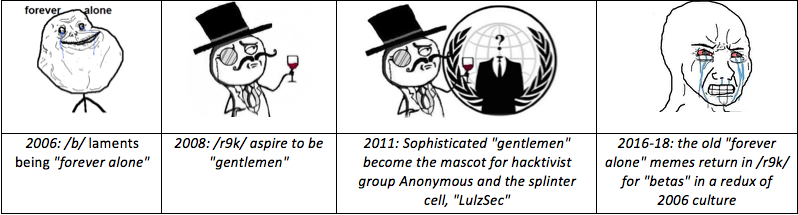

Strange to say, but there was a time when 4chan was widely celebrated in the press. Around 2008, memes had become one of the first “viral” sensations, and it didn’t take long for the media to trace the inventions to their source: 4chan, specifically the site’s more esoteric section, labeled “/b/.”

4chan was always dark and weird. One day the board might fill up with photosets of a man who lived with thousands of cartoon-themed sex dolls, the next it might be a variety of jokes about enjoying cake. Decades of multiplying fantasy worlds, screen entertainment, and pop culture had accumulated into a psychic garbage dump that overwhelmed young people. Until, that is, 4chan facilitated a countercultural response.

As 4chan gained in popularity, more people learned its unique language and culture: the gag reflex of memes, in which the endless stream of invitations to indulge in something meaningless is vomited back up in a half-digested colorful gush of irreverence. LOLcats, doge memes, and rickrolls define today’s 4chanesque streams of social media.

Though hardly anyone knew it at the time, much of 4chan’s user base had an even more ambitious project in the works: They were coalescing into an international collective of freedom-fighting hacktivists who quickly went toe-to-toe with the Church of Scientology, corporations like PayPal and Mastercard, and autocratic governments in the Middle East during the Arab Spring. They called themselves Anonymous.

Thus, by 2008, a community founded in ultra-nihilism had morphed into a place of optimism and idealistic rebellion. They had changed the world’s culture with memes. And in their conflict with the Church of Scientology, they had discovered agency as a political organization.

What was next on the slate?

Themselves. Radical self-improvement. Wouldn’t it be funny, they reasoned, if they all left their mother’s basements and computer screens?

To this purpose, they wrote crowd-sourced guides on how to better themselves physically, emotionally, and intellectually. The guides started with basic grooming tips, moved to physical exercise routines and courses of study, and ended by tackling the big existential problems.

Whereas nearly all of 4chan’s original boards in 2003 were dedicated to some mix of anime and fetish pornography, by 2008 the site included boards for topics like fitness, fashion, and travel.

Also in 2008, another board was added to 4chan, this one intended to be the heart of 4chan’s creative aspirations, a “new /b/” called “ROBOT 9000,” or /r9k/ for short. (A name that is, in part, an obscure reference to the popular anime Dragon Ball Z.) Whatever influential invention might come next after memes and Anonymous would come from /r9k/.

In /r9k/, former self-identified “/b/tards” took to calling themselves “gentlemen.” In their cartwheeling way, they converted their old jokes about how they were “forever alone” in their mom’s basement, to jokes about how they would now become the height of sophistication.

(Illustration: Dale Beran)

Flash forward to 2012, and the most prominent members of the Anonymous political movement had been hunted down by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and placed in jail. All that 2008-era optimism had dissolved, replaced by the old nihilistic resignation that counterculture could not change the status quo.

As for 4chan, well, that shimmering moment of possibility was over. As with Occupy Wall Street, it had vanished in the blink of an eye. Those who had not grown up or out of the boards—or left with the Anonymous hacktivist movement to other sites—retreated back into despair, to celebrate once again a lifestyle of remaining “forever alone” behind their screens.

In January of 2011, Poole, the de facto boy emperor of 4chan, had quietly deleted /r9k/ because “it had never served its purpose.” But at the end of the year he was forced to re-instate it as “ROBOT 9001.” People had been congregating there, just not the kind whom Poole had imagined. /r9k/ now held a vast community of young men who wanted to withdraw from life and live alone. They had been attracted to /r9k/ because of the name. Many claimed to be autistic or on the Asperger spectrum and so identified as “robots.”

There was a flowering of new terms to explain their sad circumstances: robot, beta, incel, vocel (“voluntarily celibate”), and NEETs (“not in education, employment, or training”). Lately, a new subgroup of “beta women” has been added who (half-jokingly, as usual) call themselves “Pretty Princesses.” Now that China has adopted a Western model of capitalism, we can append to this list “diaosi,” which means both “otaku” but also connotes an everyman, the new typical Chinese young person.

Often when someone comes to identify on this axis, they also adopt a literal-minded fixation on a pecking order that grants betas their namesake.

The “virgin killer” Elliot Rodger obsessed over material manifestations of his status, frustrated that, though he owned the right clothes and products, he still felt worthless. Indeed, both Rodger and James Fields Jr., the alt-right killer in Charlottesville, Virginia, used the sports cars their parents had given them to boost their confidence to carry out their respective massacres.

(Screenshot: 4chan)

How could they be well off and yet still miserable and marginalized? The betas and the alt-right are not necessarily lower class; rather, to borrow a phrase from the philosopher Hannah Arendt, “they are the refuse of all classes.” Removed from the circle of humanity like Frankenstein’s monster, they lack definition, identity, and self-worth. For this reason, they are attracted to movements that offer them “pride” and solidarity. Groping for any connection to human beings that hasn’t been shredded, they often turn to solidarity through race and, to a lesser extent, through gender. Though they tend to perceive their problem as simply economic, it is just as much a spiritual one, the broken lack of meaning at the center of nihilistic accumulation.

One’s view of society is generally only this distorted when one’s standing at the very top or bottom. The young men form an alliance with these they perceive as their champions among the “winners” at the summit of the same hierarchy that has ground them underfoot: Donald Trump, Milo Yiannopoulos, Steve Bannon. Aping the Donald Trumps of the world, they imagine human interaction as a competition for power among rivals.

Indeed, beside /r9k/, a new politics board on 4chan (/pol/) soon filled up with “paranoids, trolls, white nationalists, betas, libertarians, and directionless adults”—at least according to their own memes on the subject. Within a year, it had coalesced into the entrance to the quagmire of the Nazi-worshipping alt-right.

Here is Arendt’s description of the proto-fascist movements that appeared in 1920s, the last time inequality was as high as it is today:

[They] grew out of the fragments of a highly atomized society whose competitive structure and concomitant loneliness of the individual had been held in check only through membership in a class. The chief characteristic of the mass man is not brutality and backwardness, but his isolation and lack of normal social relationships.

Sound familiar?