The national suicide rate is at its highest in nearly 30 years. Why?

By Jared Keller

(Photo: Silvia Sala/Flickr)

So much for a country built on boundless optimism. More Americans are committing suicide now than at any other time in the last 30 years, according to a new analysis by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The NCHS study released last week indicates that the national suicide rate jumped an astonishing 24 percent (to 13 in every 100,000 people) between 1999 to 2014, the highest it’s been since 1986, according to the New York Times. The increase was particularly pronounced among middle-aged Americans between the ages of 45 and 64: Suicide rates for middle-aged men jumped 43 percent, while the suicide rate for women grew by a whopping 64 percent. In 1999, 29,199 people died by suicide; by 2014, that number had spiked to 42,733.

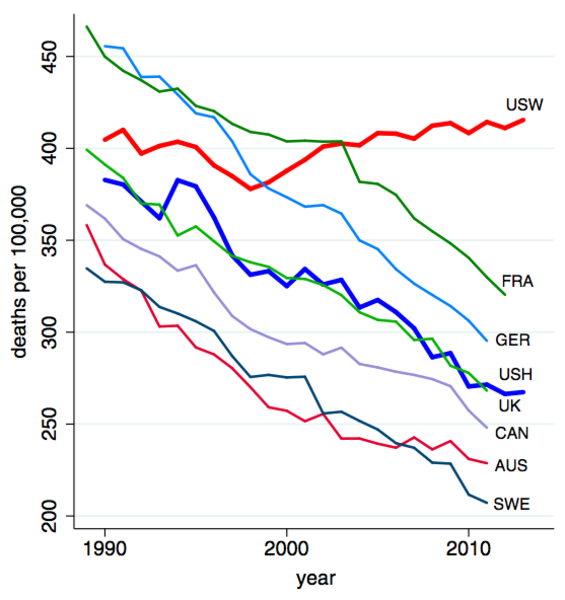

The study follows alarming research published in the Proceedings of the Natural Sciences last year that showed middle-aged, white Americans have been dying at a greater rate than ever before. Starting in 1998 — around the same time as the increase in the national suicide rate observed in the NCHS study — the United States saw “half a million deaths” among middle-aged white Americans alone. As mortality rates declined in almost every developed nation (except for Russia), they rose steadily for the U.S., resulting in this eye-popping chart:

(Chart: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

So what’s eating white America? As I noted when the PNAS study was published in November, suicide is a frequent indicator of a broader social dysfunction. That’s been the case since Émile Durkheim’s groundbreaking 1897 book Suicide transformed sociology into a study of social facts rather than an exercise in political philosophy. The core concept from Durkheim’s analysis is anomie, “a condition in which society provides little moral guidance to individuals,” where citizens morally disconnected from the broader civil society through economic, political, or social upheaval find themselves without solidarity and belonging. For those tasked with providing for their families, their perceived helplessness combined with a lack of social integration can be particularly deadly.

“The role of suicide, drugs, and alcohol in the white midlife mortality reversal is a signal of heightened desperation among a population in measurable decline,” Paul Starr wrote in the American Prospect in November. “The phenomenon Case and Deaton have identified suggests a dire collapse of hope.”

As it turns out, inequality kills.

That this sense of despair is centered on middle-aged, economically disadvantaged whites with less education makes complete sense in the context of Durkheim’s suicide hypothesis; after all, it’s those whites who have certainly been left behind economically, politically, and socially. Consider that some three-quarters of the eight million jobs lost during the Great Recessions were in manufacturing—the sort of trade that primarily employed white men. And those jobs aren’t coming back any time soon.

Or consider that, with an electorate that’s growing increasingly diverse and shaped by non-white demographic groups, whites of all genders are experiencing a relative (if not totally catastrophic) erosion of their relative political clout. And consider that those financially stressed, lesser-educated voters are far less engaged with the civic institutions of American life (to a degree that might make Robert Putnam shudder).

Of course, the experience of anomie is relative for this troubled group. Objectively, minorities don’t enjoy the same comforts as white Americans. The mortality rate among African Americans is still significantly higher than whites, as is the unemployment rate; and the majority of the gains from the economic recovery have flowed to white Americans, both men and women. The white American experience is still represented and reinforced more than any other group in the media and broader culture. And as I wrote in November, the daily stresses of living as a black person in the U.S. are far more traumatizing than the daily inconveniences of whiteness. Whites have taken their privileges for granted, and any relative deprivation is far more disconcerting and debilitating for them than marginalized groups that have spent their lives getting a raw deal in the U.S. political economy.

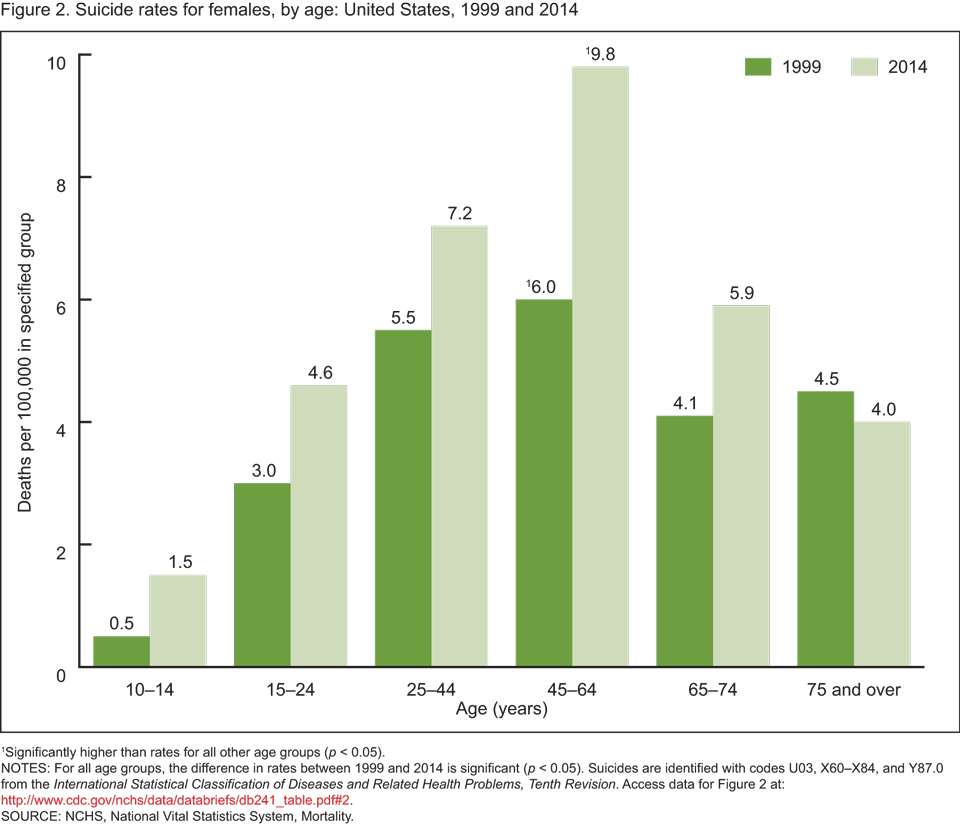

It’s unclear as to why the jump in suicides over the last 30 years has affected women in particular. While the overall rise in the national mortality rate has equally affected white, less-educated men and women, a 21 percent difference in the change in the suicide rate between the sexes is worth noting. Almost every age group for women in the U.S. saw increases in suicides, with those middle-aged women between 45 and 64 experiencing the largest increase.

(Chart: National Center for Health Statistics)

If we take social turbulence and relative deprivation as indicators of despair, the economic experience of women during the Great Recession may lend some clues. The Economic Policy Institute notes that, while men lost far more jobs than women during the 2008 global financial meltdown, they also enjoyed significantly more economic gains; while women added 3.6 million jobs between February 2010 and the June 2014, men gained 5.5 million. While women made up more than half the workforce in 2011, their jobs continue to be marred by the injustice of gender equity. Women are also paid less than their male co-workers, and are so often squeezed out of the maternity leave the rest of the advanced world enjoys.

That the persistence of gender inequality amid the political and economic turbulence wrought by the turn of the century affects the national suicide rate makes sense: A 20-year examination of the cultural influences of suicide in 33 nations found that countries with a high level of “power-distance” — one of Geert Hofstede’s cultural values that describes countries with significant stratification between finances and other sources of cultural power — experienced high rates of female suicide. As it turns out, inequality kills.

Despite the economic gains experienced since the end of the Great Recession, these studies suggest that American society remains in a particularly perilous state. Politicians can talk as much as they want about how the nation has “recovered” from the chaos of an economic free fall and the psychic toll of two wars, but until the suicide rate levels off or begins to decline, that recovery may be all in their heads.

||