“You’re like a cult!” my friend Katie told me at the tail end of a recent girls’ night. A bunch of us were gathered on an L-shaped couch and the conversation had turned to periods, as it does after a few glasses of wine among girlfriends — some spin on the age-old tale of being caught without a tampon. I’d just interrupted her story with a Pavlovian outburst. I had raged against tampons and urged Katie to get a menstrual cup instead.

“You seriously have to get a cup. I bought one five years ago and I’m so obsessed with it that I haven’t bought a tampon or a pad ever since. They’re amazing and you need one — ” I began.

“Yeah, yeah, I know,” Katie replied. “I mean, I’ve already heard you say this. We’ve had this entire conversation before.”

When it comes to menstrual cups — reusable, funnel-shaped devices made of flexible silicone that can be inserted into the vagina to collect menstrual fluid — the overwhelming majority of women are reluctant to make the switch. Some 98 percent of American women manage their periods with a combination of disposable tampons and pads, while a combined 2 to 3 percent opt for reusable products — a category that includes cups, as well as washable fabric pads and sponges — according to Sophie Zivku, the communications and education manager at Diva International Inc., which produces the menstrual-cup line DivaCup. As I reported this story, the reasons why women are reluctant to make the switch were echoed by everyone from academics to marketing experts to friends: Women are grossed out about touching a menstrual cup, nervous about changing it, stymied by inserting it, and besides — their friend Brianna From College tried one and it totally leaked.

Cup devotees, nevertheless, have several good reasons to evangelize their tampon- and pad-free lifestyles. Menstrual cups are cost-effective: While the average woman spends thousands on some 17,000 tampons and pads over the course of her menstruating life, one menstrual cup costs between $20 and $40 and doesn’t ever need to be replaced. They’re environmentally friendly too: Menstrual cups provide 12 hours of continuous protection, compared to disposable alternatives that must be changed every few hours. They contain safer ingredients, and feel less obtrusive without diaper-esque padding or a dangling string. One 2011 study showed that 91 percent of the subjects who tried them would recommend them to friends. There isn’t a woman on Earth who feels that passionately about tampons.

Not even habitual users particularly like tampons: Regular tampon users report feeling more satisfied with menstrual cups than their usual means of menstrual management. Those who don’t use tampons cite a number of alarming reasons why: They find them uncomfortable, potentially hazardous to their health, unintuitive to insert, even unnatural. And yet, the overwhelming majority of American women (81 percent) continue to use tampons, either alone or in conjunction with pads. How did we get like this, when a better option has long been right in front of us?

In an era ruled by the dogma of innovation, we tend to take it for granted that cheaper, more convenient, and more beloved products creatively destroy their costly and inefficient competitors. But as the long, unfinished history of the menstrual cup’s road to mainstream acceptance demonstrates, transformative shifts in consumer behavior require the cooperation of social norms, effective entrepreneurs, and extenuating circumstances too. These challenges have prolonged the rise of the menstrual cup. Its sputtering history sheds a light on the cultural and corporate factors that have long protected the feminine hygiene industry from being disrupted.

If the options for contemporary menstrual management aren’t perfect, they’re at least understandably flawed. The commercial sanitary care industry has only been around for a century, during which time it’s tackled not only the usual engineering dilemmas faced by start-up technology businesses, but also menstruation’s immense and long-standing cultural baggage.

Stigma surrounding this healthy, natural process has been around for millennia. In many ancient hunter-gatherer cultures, women spent a week per month in retrospectively dubbed “menstrual huts,” stowed safely away from villagers who didn’t have their period. Some indigenous Amerindian cultures, interpreting menacing potential in menstrual blood, prompted rogue witches to incorporate it into magic spells. Even Aristotle characterized menstruation as evidence of women’s inferiority — the blood, he reasoned, must be a result of the body’s botched attempt to produce semen.

Periods have traditionally been so hush-hush that women’s own experiences with their menstrual cycles are practically absent from the historical record. What little we do know about sanitary protocol before the 20th century paints a bleak picture: Some historians argue that insufficient period management products may have kept women from venturing too far from home one week each month, thereby preventing them from fully participating in the public sphere. Most women had no choice but to bleed into their undergarments, packing dark ones for the purpose, historian Laura Kidd concluded in her 1994 dissertation on American menstrual technology.

What little we do know about sanitary protocol before the 20th century paints a bleak picture.

Doctors’ accounts, meanwhile, demonstrate that men of the era capitalized on menstruation as a justification for gender segregation. One influential 1873 book by Dr. Edward Clarke, Sex in Education or a Fair Chance for the Girls, argued against educating girls during their periods. (His reasoning? Learning about their own bodies would wreak havoc on their cycles by diverting blood flow to their brains.) Clarke’s sentiments were echoed by Dr. Azel Ames two years later — Ames argued that periods should disqualify women from most types of work.

At the same time, Victorian fashion threw obstacles in the direction of would-be menstrual entrepreneurs. Until the 1920s, women’s undergarments fit far more loosely than they do today, with the crotch hanging several inches below the labia; finding a way to rig absorbent material so that it stayed close to the body was no easy task.

Menstrual technology got its big break when women’s fashion changed to reflect their more active lifestyles in the late 19th century, as women’s roles expanded to include more employment outside the home. Several early products promised women simpler lives during their cycles, according to Kidd. Between 1854 and 1921, several patents were granted for menstrual napkins that could be pinned or clipped to belts or suspenders. These products flopped, perhaps due in part to the fact that they had serious shortcomings — most changeable-napkin material tended to rip, or get twisted up during a day of use; and even with the perfect removable pad, wearing belts or suspenders under your clothes was a nightmare, chafing, twisting, pinching, and bulging out under outer fabric.

Despite their failings, it’s notable that around one-third of these early patents were filed by women, disproportionately higher than the approximately 2 percent of patents they filed during that time overall. Women’s insight into the practical concerns menstruation presented in everyday lives offered hope for future innovations — all products designed to conceal stains, for instance, were filed by women.

Women didn’t just popularize and develop some of the earliest pads, they played a formative role in marketing them. By the early 1900s, many women had adapted commercially available gauze and diaper fabric for menstrual purposes. These materials, and the accoutrements needed to keep them in place, were advertised in the pages of periodicals like Harper’s Bazaar (some of them even assured timid customers their orders would be filled by “a competent lady”). Other small-scale agencies selling “antiseptic napkins” and belts posted ads seeking “lady agents” to sell their products door-to-door, answering sensitive questions that euphemistic marketing copy couldn’t.

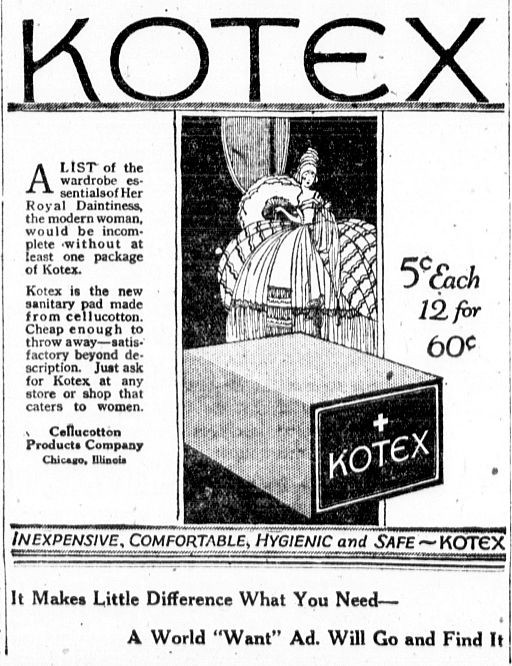

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

True liftoff for sanitary care products, however, would take a war — and a company that paid attention to what women were doing. When the so-called “Great War” broke out in Europe in 1914, a small Wisconsin paper company called Kimberly-Clark landed a contract to supply surgical dressings to hospitals overseas. The company must have been relieved to have a use for its odd new material, “cellucotton,” made from a pulp blend of cotton and paper, which it had developed in a momentary panic over tumbling newsprint prices before the war. After the 1918 armistice left the company with a major surplus of these dressings, Kimberly-Clark uncovered a new use for the material. French war nurses had apparently been repurposing the extras as sanitary pads — a trick that Kimberly-Clark decided to copy wholesale. It turned out the first major commercial feminine hygiene product — a pad — in history. In 1921, “Kotex” hit the shelves. By 1927, consumer surveys showed they were already more popular than homemade reusables.

Of course, being better than its competition hardly said much about Kotex, given that historic alternatives had been so bad some women opted to free-bleed in their homes. So other would-be entrepreneurs kept on pushing.

A few years later, yet another woman came up with a clever fix for a vexing conundrum from her own day-to-day life. One July day in 1935, Leona W. Chalmers filed a remarkable application at the Philadelphia branch of the United States Patent Office: a funnel-shaped receptacle of vulcanized rubber inserted low into the vagina to collect menstrual fluid, rather than soak it up like a Kotex pad did. Chalmers’ tediously named “catamenial appliance” was so paradigm-busting that it was never fully appreciated in her own lifetime — nor, as of yet, in mine.

Chalmers’ invention was inspired by her bygone days as an actress, working a grueling schedule that didn’t yield to the inconveniences of monthly cycles. Sometime around the turn of the century, Leona Watson — Chalmers’ maiden name — stole off to New York City from her native Kentucky and, within a few years, landed a job at the Harold Square Opera Company, starring in U.S.-touring productions. In 1909, she got her big break by landing the lead role of Adelina in the upcoming Broadway premiere of The Climax, a cliché rags-to-riches story that delighted contemporary observers.

“The record of this young girl’s remarkable success reads like a fairy story,” one reporter wrote. Some recounted an anecdote that showed an audacious streak foreshadowing her future re-invention as an unconventional entrepreneur: Before she hit gold with The Climax, a repo crew surprised the Watsons in Kentucky and lugged away the family piano, which Leona had secretly pawned to bankroll her pricy East Coast voice lessons.

One less glamorous aspect of Watson’s touring career was that, while she was “barnstorming” from stage to stage, she faced the challenge of how to avoid menstruating all over Adelina’s angelic white dress. Not only was Kotex still a decade off, but the bulky straps, suspenders, and girdles that kept pads in place at the time would be glaringly obvious beneath a delicate gown — not to mention the stage lights. Watson and her menstruating castmates avoided such unsightly external heft by rolling up scraps of fabric and manually inserting them, creating something akin to homemade tampons.

(Photo: Courtesy of Kelly O’Donnell)

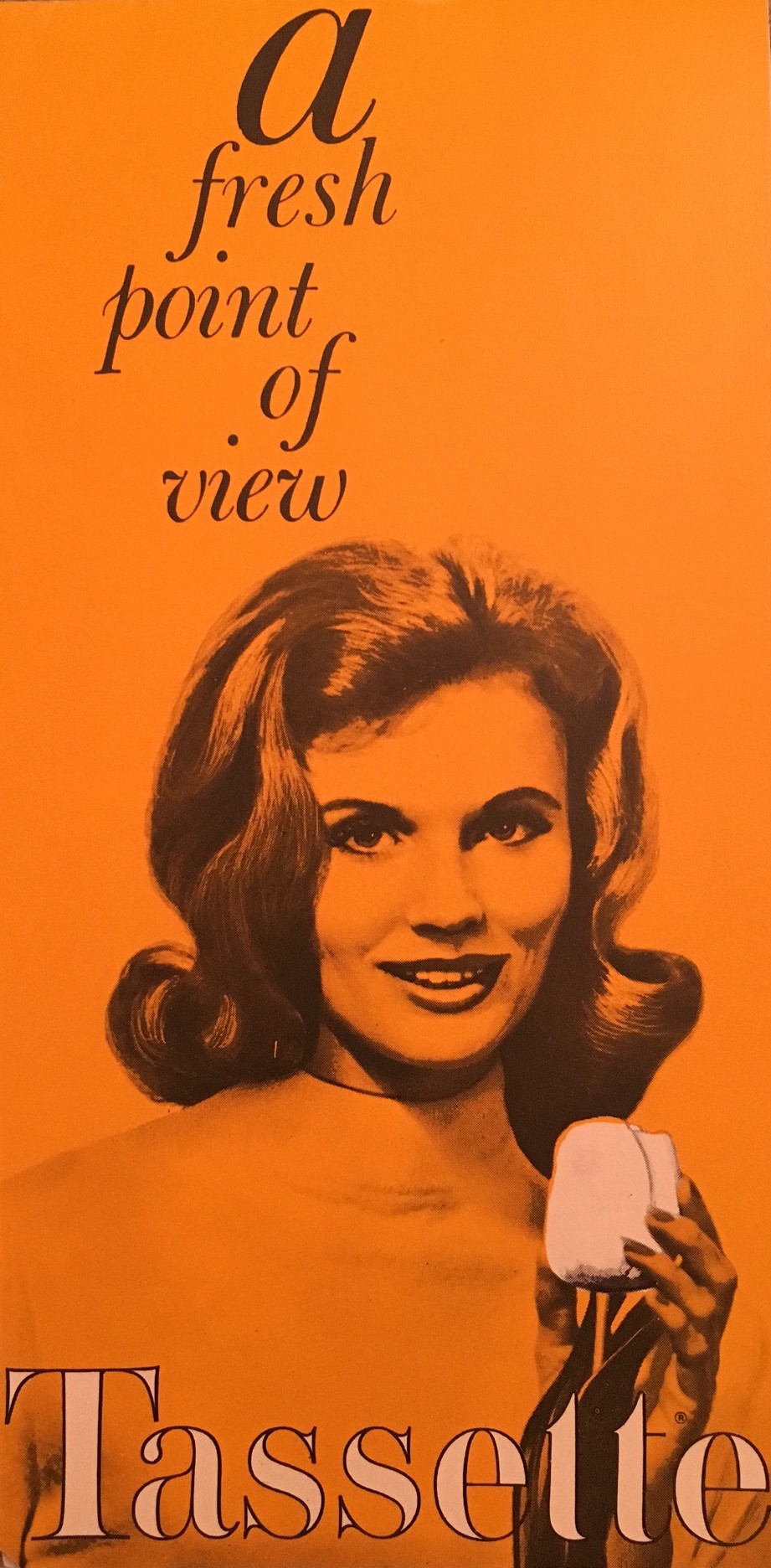

That this solution was already revolutionary for the time didn’t stop Watson from continuing to contemplate the problem. Decades later, the widowed Leona Watson Chalmers would cite those grueling six-day weeks of theater life as the inspiration for the Tassette, the first commercial menstrual cup.

It was a woman’s invention, made to simplify busy women’s lives. “Frankly it is well worth a trial, because this little device appears to be the best solution to the problem of sanitary protection,” reads one passage of Chalmers’ 1937 book, The Intimate Side of a Woman’s Life. “It eliminates belts, pins, napkins, and inconvenience … furthermore the device does not have to be removed in answering a call of nature. It is truly a Godsend to professional and business women.”

These practical virtues were reflected in the Tassette’s initial ad campaign. One of the first ads for the funny new product appeared in Photoplay magazine in 1937. “Mrs. Leona W. Chalmers invents invisible protection … so comfortable you’ll never feel it … so secure you’ll always be at ease!” the copy read. “IT TOOK A WOMAN to ease women’s most trying ordeal.”

Chalmers’ invention had all the promise to become the product of choice for dynamic, modern women. But a man had already beaten her to the punch.

Four years before Chalmers filed her patent, a Denver physician named Earle Haas filed his for a competing product: a “catamenial device” that would become the world’s first commercial tampon and applicator. Its origin story was described by Ashley Fetters last year in The Atlantic: After a friend confided that she’d been sliding sponges into her vagina to soak up her menstrual flow, Haas adapted the idea using tightly bound cotton instead.

Tampons — the French word for “plug” — weren’t exactly a novel concept. For over a century, doctors had halted bleeding and infection by stuffing patients’ wounds with compressed cotton (Haas, a physician himself, must have considered it a logical means of absorbing women’s monthly bleeding too). By the 20th century, tampons were a surgical mainstay — even if the fact that resourceful World War I-era French nurses reached for pads, and not plugs, illustrated that tampons, if medically accepted, weren’t the intuitive solution for menstruating women.

Tampons weren’t embraced immediately. In fact, tampons and menstrual cups would face similar challenges to mainstream acceptance in an era of pads. Tampons overstepped cultural boundaries: Insertion required extensive contact with the genitals, and could undermine one’s “purity” by snagging the hymen. Insertable products also evoked certain forms of clandestine contraceptives, internally worn oddities advertised so euphemistically that historians like Kidd are at times uncertain which products served which purpose. When Kimberly-Clark’s marketing firm ran early field tests whose subjects included its own female employees, one woman complained that she was “very frightened when [she] removed the tampax for I felt as if I were pulling all of my organs out of place.” Tampons were, in essence, terribly unsettling.

But others gradually warmed up to the tampon, portending how women would eventually come to accept the new technology en masse. “I am sure that on my own volition I would never even consider using an insert with such a wicked appearance, that is, so painfully stiff and so incredibly long,” one woman reported. “After much consideration, though, I am beginning to appreciate the unusual features of this strange appliance.”

The first time I heard about menstrual cups, I must have sounded just as quaint as the tampon-using pioneers of the 1930s. I was a 22-year-old Peace Corps Volunteer in Ukraine just getting used to the applicator-free tampons available at my site when I started hearing about colleagues in the field who were switching to an alternative product called the DivaCup.

At first, I was utterly unconvinced by the other volunteers’ enthusiastic reviews. “You use what?” I demanded, making them explain the cup concept to me over and over. It sounded so weird I could barely even picture it, though I had trouble articulating exactly where my revulsion was coming from.

In retrospect, it feels odd that I had such reflexive loyalty to a product that I never even liked. I hated the feeling of an hours-old tampon sliding downward under its own weight, or of a damp string rustling around after you pee. I hated how the applicators always poked through their shitty wrappers inside of my purse, forcing me to dig around for loose tampons on the toilet. I hated the goosebumps-inducing, dried-out sensation of yanking one out on the last day, and the internal adjustment shimmies I’d have to make when I put one in at the wrong angle.

I finally decided to try the DivaCup when I returned stateside two years later. Per the instructions laid out by DivaCup’s squee pink introductory pamphlet, I folded the cup inwards to insert it. Then I spun it around by the bottom for one full rotation so it opened up and formed a good seal between the rim and the vaginal wall.

In retrospect, it feels odd that I had such reflexive loyalty to a product that I never even liked.

All that morning, I kept taking paranoid bathroom breaks to check on it. Was it still in? Was it full? How would I know? If I coughed and felt it shift a tiny bit, was that bad? By lunchtime, I’d concluded all my worrying had added up to squat. I had that dopey swell of excitement common among the dozens of cup ladies I’ve spoken to for this story: This thing is the best, I thought. I only ever have to change it in the morning and at night, in my own bathroom! Once I put this thing in, it feels like nothing! I’m going to save so much money! And I’m going to save the Earth doing it!

Soon enough, I was hooked. Years later, I am still struck by the number of annoyances that have been eradicated from my life after having done nothing more than swap products.

But my conversion from skeptic to true believer was long, and full of snags. These hurdles are all-too-familiar to menstrual cup companies gunning for mainstream acceptance: the knee-jerk disgust, the learning curve, the tween trauma reboot when I bungled the seal and leaked onto my (mercifully black) skirt.

As challenging as these barriers may be, they’re hardly new. (Let those among us who have never stained our clothing cast the first stone!) As one middle-aged woman in the Kimberly-Clark study put it some 80-odd years ago, tampons would “undoubtedly … please the young moderns. Older women, hampered by old fashioned training and ideas will hesitate to use them. I don’t know why, but I would not feel safe.” History tells us that we change what we use only after we change how we think.

If tampons and menstrual cups were both relatively whacky and scary ideas when they emerged in the 1930s, why did their respective 80-year trajectories pan out so differently? Two reasons: marketing, and World War II.

History is hardly short on men making fortunes off women’s problems, but Haas was not destined to become one of them. To entice buyers, he’d given his product a spiffy new name, Tampax, and, in 1934, sold its exclusive patent rights to a Denver businesswoman named Gertrude Tendrich. Tendrich started churning the things out on her own home sewing machine, became the first president of her new company, and ultimately steered the tampon to mainstream success.

Bizarrely, Tenderich relied on a team of men to roll out her new Tampax. They aggressively marketed the product: As told in a 1936 booklet published by the company, one of their sales tricks was waltzing into a drug store, asking for a cup of water, and dunking in an unused catamenial appliance to regale the druggist with its absorbency.

This scrappy door-to-door salesmanship was bolstered by a massive print ad blitz that introduced the tampon to some 20 million readers of Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, and elsewhere. After more than a decade of Kotex’s stratospheric rise, other companies like Kimberly-Clark took note of Tampax and churned out copycat tampons of their own, and businesses with clout, distribution, cash, and marketing firms quickly catapulted the new product to fame.

Compare that well-executed launch to Leona Chalmers’ scrappy do-it-yourself sales tactics: Chalmers placed ads in showbiz trades, not top-tier glossies. She wrote two hygiene-centric books that included sections on the Tassette, but never found many readers (despite intriguing section headings like, “My Favorite Positions for Douching” — which appears in both texts.)

Like the Kotex sanitary napkin before it, the tampon took off because it made working women’s lives easier. It also benefitted from a serious war boost: When women flooded the labor force during World War II, tampons were a natural choice over pads for a long day of work. While their total usership was still a fraction of that of pads, tampons had begun to cement a reputation as the pick for modern, active women.

Like the Kotex sanitary napkin before it, the tampon took off because it made working women’s lives easier.

Meanwhile, the war had the opposite effect on Chalmers’ fledgling Tassette. The wartime rubber shortage closed up production for years, so the little cups couldn’t be made even if anybody had wanted them. The records show that Chalmers gave it one more shot — there are a smattering of ads for the cup in the late ’40s — but then they fall off. The things got no press; they never had a chance.

The odd, failed little cup got a new lease on life in 1958, when Chalmers pitched her product to a young businessman named Robert Oreck, who had advertised in the Wall Street Journal that he was looking to buy patents for potential product development. The story was recounted to me by historian Kelly O’Donnell, the world’s preeminent expert on the history of menstrual cups, as she calls herself to colleagues. Oreck told O’Donnell how flabbergasted he was by Chalmers’ initial call: “Getting involved with such an intimate matter as a woman’s menstruation was really beyond our imagination,” he said in an interview. But when his wife tried a sample Tassette and loved it, he was convinced — he bought Chalmers’ patent.

Under Oreck’s watch, detailed Tassette adverts landed in 17 major papers, and samples were marketed to nurses. The company turned heads by running the first-ever radio ads for feminine hygiene products in American history, and by commissioning a 30- by 40-foot billboard in Times Square: It read “Tassette: not a tampon, not a napkin,” above a groovy illustrated tulip and a dainty lady hand holding a tulip-shaped pouch. (Oreck asserted that the tulip imagery grew out of careful market research: “Women’s psychological reaction to the symbol has proved to be quick, complete, and very positive,” he said.)

Some 100,000 Tassette cups were sold after the ad blitz of the early 1960s, multitudes more than Chalmers’ trade ads ever managed, according to a report I found in the University of Iowa archives written by a former employee of Tassette, Inc. But the product still amounted to an abysmal flop when offset by production and marketing costs. Moreover, by the time the Tassette was re-born in the ’60s, the company’s target demographic of busy women was already accustomed to tampons.

(Photo: Courtesy of Kelly O’Donnell)

The Tassette team came up with one last Hail Mary to redeem the product — a re-designed cup that more closely resembled its phenomenally successful competitor. In 1969, the company debuted the Tassaway: a thinner, flimsier, and, unlike its forebear, made for one-day use model. The Tassaway was designed to do two things — sell a greater quantity of units and appeal to women who had come to expect their menstrual products to be disposable.

The company accomplished at least one of those goals. When it folded after a few short years, it left behind a small but passionate fan base. In her research, O’Donnell found that some 20,000 women wrote desperate letters to Tassaway, Inc. when its products vanished from the shelves in the mid-1970s. “Help! I have run out of your product and cannot find it on the shelf of any store, anywhere!” one particularly distressed woman wrote. “If you have taken your product off the market … please send me a two years’ supply of what you have left … I am tired of flooding, soiling, and itching. PLEASE RESPOND SOON!”

It was the third incarnation of Chalmers’ invention to die, which rational people might see as ample evidence of a stinker. But the enthusiasm gap between users of cups and users of tampons hints at a different story. The fate of both products has ultimately been determined by a complimentary set of advantages: The menstrual cup is a great innovation that makes for so-so business; the tampon is a so-so innovation that makes for great business. Every major pad and tampon brand has eventually enjoyed increased visibility and distribution after being acquired by a larger company, but this has never been a viable path for the cup: Why would the likes of Proctor and Gamble want to rule out repeat customers by selling every woman one cup, when they can instead sell her tampons for decades?

Tassaway’s demise was colossally bad timing. As it happens, the company faded out just as some of the cultural issues holding it back began to change.

The 1970s witnessed a revived feminist movement that changed the dialogue surrounding women’s bodies, and taboos surrounding their genitals. The environmental movement started picking up steam, generating interest in sustainable lifestyle choices.

And, a short time later, tampons weathered a debilitating crisis of their own: In the early 1980s, the products were linked to nearly 2,000 cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome, a rare but serious disease that can be fatal. The crisis forced tampon manufacturers to issue warnings and usage recommendations, as well as submit to more regulation under the Food and Drug Administration — albeit at a lower level than many advocates think necessary.

The time has been ripe for the menstrual cup to catch on since the 1980s — so why hasn’t it? One reason is that, in the years when TSS shook consumer confidence in tampons on a mass scale, there were no cups on the market to catch unsettled defectors: The Keeper, the next major commercial cup, wouldn’t debut until 1987, by which time TSS panic had all but subsided.

But the fact that a scandal as monumental as TSS had a relatively minor impact on the tampon industry is also a testament to the cultural inertia that keeps tampons entrenched in our lives. Habits surrounding menstrual products are often passed on from mothers to daughters, according to Breanne Fahs, a humanities professor at Arizona State University and a member of a community of self-proclaimed “menstruation activists.” These first impressions, she says, follow us throughout our lives. “Menstrual products are either introduced by early menstrual education classes, or more likely by their parents, probably mothers,” Fahs says. “If mothers of teenage girls don’t know about these products, they can’t introduce them at earlier stages — so tampons and pads become what we internalize as normal.”

Girls are also highly unlikely to get any information about menstrual cups in school. The majority of U.S. elementary schools conduct a puberty education program called “Always Changing,” a curriculum created and distributed by Always pads that includes free product samples and instructions.

(Photo: menstruationstasse.net/Flickr)

Nevertheless, the menstrual cup’s outspoken cult following suggests that the future is bright for the long-delayed technology — even if menstruation activists are largely relying on the same marketing tactics they always have. Cups are often sold and promoted by a cadre of trustworthy “lady agents” who connect with, re-assure, and educate rookie cup users in ways traditional marketing never could. These enthusiastic ambassadors run the gamut from self-appointed fans to official partners of various cup companies, and they emphasize pushing back against menstrual stigma. “If someone says, ‘Oh, it’s my time of the month,’ I’ll say, ‘Oh, you’re menstruating?’ just to forward that conversation,” says Ph.D. student and menstrual activist Jacqueline Gonzalez, who includes cups in the menstrual workshops she conducts at various colleges.

Other menstrual-cup advocates appeal to the technology’s environmental benefits. Sarah Konner and Toni Craige, the founders of the grassroots organization Sustainable Cycles, for instance, educate people about re-usable products and create Web resources and pamphlets about how to use them. They have spearheaded cross-country bike tours during which they sponsored workshops and discussion groups, and distributed cups and materials. “We gave out cards,” Konner says. “We told people, ‘Even if you’re on the toilet and can’t figure it out, call us!!!’” (One subsequent call involved Konner walking someone through the process of removing a cup the user swore was stuck.)

Recent research suggests this approach is effective — menstrual cups have a particularly high pick-up rate among women who were introduced to the product by their peers. As such, social media has been a transformative resource for menstrual-cup brands. “One of the main things with social media is two-way conversations — you don’t have that with print ads,” says Sophie Zivku, the communications and education manager at DivaCup. “All of a sudden, videos on period care are going viral on YouTube. I am interested in how that’s framing new discourse about periods.” One such difference boils down to intensity — according to Zivku, cups tend to be discussed online with much more detail than disposable products.

“Women are describing flow, and how to insert it … they’re not beating around the bush. They’re being very specific. There’s definitely a lifestyle element,” Zivku says. The frank discussions have yielded practical results: In the past few years, DivaCup is now carried by massive chains like REI, Whole Foods, and CVS, and LilyCup raked in thousands on a Kickstarter to develop a discreet cup that folds into a compact. (Another Kickstarter for a so-called “smart menstrual cup” that measures fluid level has raised plenty in donations, despite being astonishingly unnecessary.) At long last, these advocates have helped the menstrual cup enter the mainstream like never before.

If Chalmers were alive today, she’d probably be baffled by the delay. After all, her marketing campaigns’ impassioned appeals to audacious, on-the-go women of the past feel perfectly at home today. “Modern women cannot afford to … deny themselves outside interests during the period,” Chalmers wrote in her 1941 book Woman’s Personal Hygiene. “We live in an entirely different world from that of our mothers and grandmothers. The methods employed by them do not fit into OUR WORLD. The part women play in the world today demands self-confidence, mental freedom, and complete unconsciousness of the menstrual condition.”

Reading this now, it’s easy to see how Chalmers’ granddaughters took after her: We barnstorm around the world, we take risks and follow our dreams, we discuss our bodies on our own terms, and develop solutions to problems that complicate our lives. And if we can’t quite eliminate periods from our consciousness, Chalmers’ cup gets us awfully close.