One of the more glaring differences between the Democratic and Republican parties right now is their approach to the 2016 presidential election. Party elites, as the authors of The Party Decides explain, are capable of coordinating support behind a favorite candidate and making sure that person gets the nomination. But one party has used that power vastly different from the other this cycle.

Democratic Party elites have effectively anointed Hillary Clinton as their nominee, and there was never really much doubt, going as far back as 2009, that the nomination was hers if she wanted it. This is pretty astounding for what is really an open-seat election, which usually feature competitive primaries and caucuses in both parties. The Democrats converged on a nominee earlier and more thoroughly than ever seen in a modern presidential race in which the incumbent wasn’t running—nearly half of congressional Democrats had endorsed her by last month. Even some incumbent presidents face stiffer competition than this within their party.

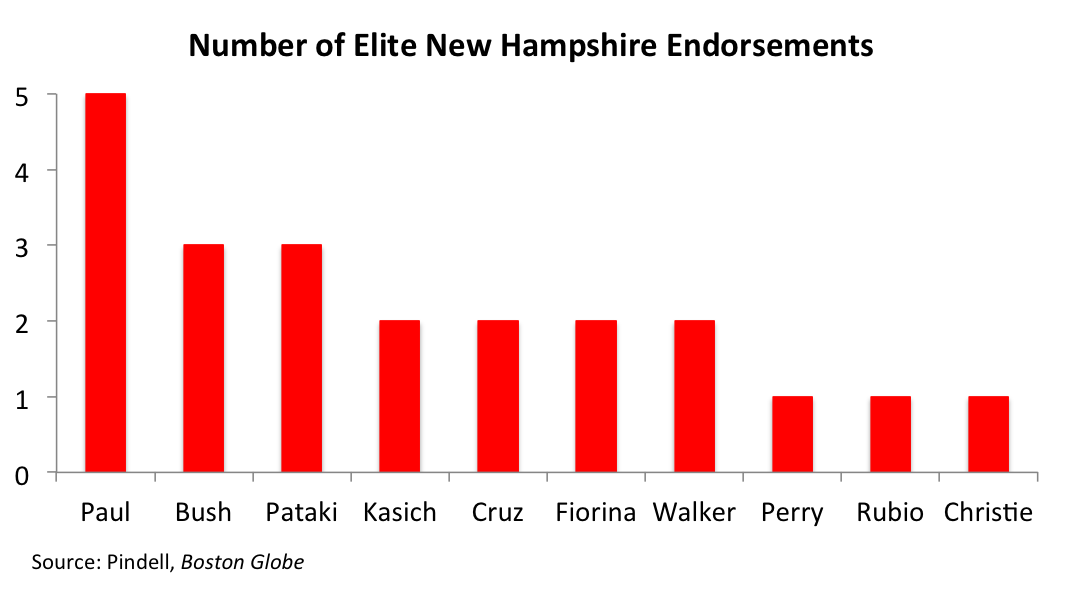

The story is very different on the Republican side. To get a sense of it, note James Pindell’s wonderful tabulation of 106 top New Hampshire Republican activists in the Boston Globe. Pindell has been keeping track of which of these party elites in this key early contest state has endorsed which presidential candidate for 2016. Note the endorsements so far:

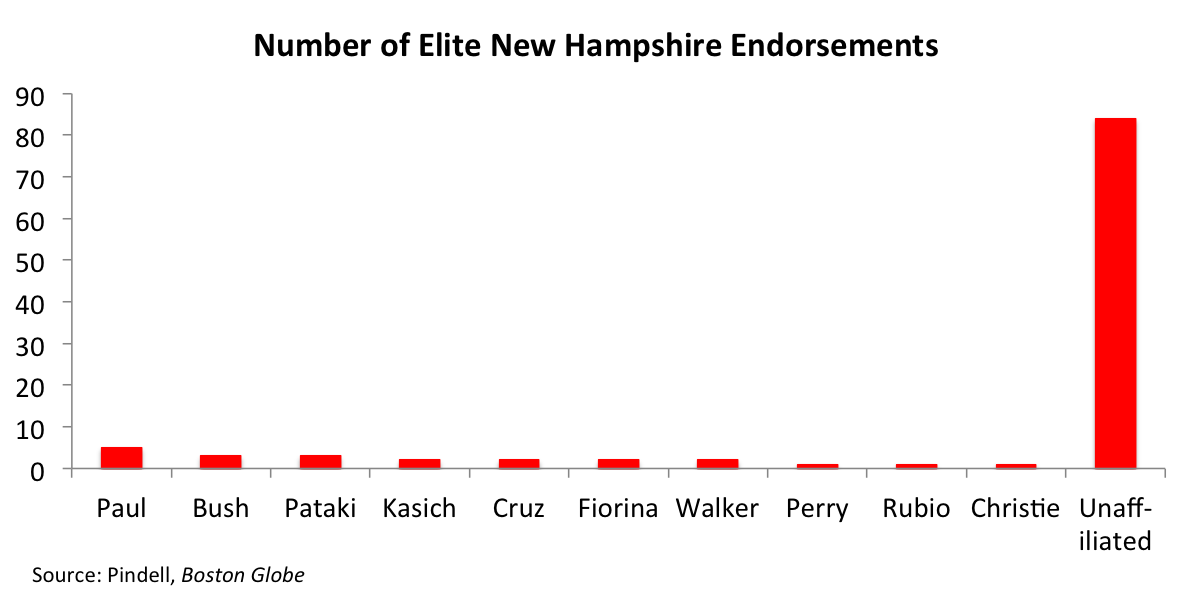

Rand Paul actually has an early lead among New Hampshire endorsers, reflecting the passion and commitment of some of his supporters. But probably more interesting is the number of non-endorsements so far. Here’s another way of looking at the data:

What this suggests is that the deciders haven’t yet decided. Other evidence supports this. As Nate Silver and Harry Enten noted, only a handful of members of Congress have supported Jeb Bush (considered a front-runner by many pundits), and basically all of those are fellow Floridians. Rand Paul’s biggest endorsement so far comes from fellow Kentuckian Senator Mitch McConnell. Marco Rubio is mainly backed by Floridians at this point, and Huckabee by Arkansans. That is to say, none of the endorsements are particularly surprising; it’s mainly people from the candidates’ home states. (OK, Scott Baio backing Scott Walker is somewhat surprising. Baio’s from New York, but then, of course, Chachi was from Wisconsin.)

So why are Republican elites sitting back and watching right now instead of jumping in and steering? Well, for one thing, there’s no need to fear a crowded field just yet. Yes, the debates could be a bit messy, but they’ll likely be entertaining and draw (relatively) large audiences. A crowded field could become risky by early 2016; if party elites are comfortable with, say, Bush, Walker, and Rubio, but they end up splitting the same portions of the electorate and handing a lot of delegates to, say, Cruz or Paul, that’s a potentially bad outcome from the perspective of many party leaders. But they still have plenty of time to winnow the field.

Another reason not to actively narrow the field is because there are several good but inexperienced candidates in the mix. Walker and Rubio both show significant political strengths but were all but unheard of outside their states just five years ago. Jeb Bush has an impressive pedigree—Republicans usually win presidential races when they nominate Bushes and usually lose when they don’t—but he’s been out of the game for a while, and his recent fumbling over Iraq War questions suggest his political skills need some honing. By letting the race play out for a while, party elites get many chances to actually see how good such candidates are and who could get through a general election without committing massive errors.

Finally, it’s worth noting that some significant winnowing is already occurring. As Jonathan Bernstein notes, Mitt Romney, Rob Portman, and John Bolton were actively running for president and have now dropped out. Quite a few of the people who are still in the race, due either to their professional background or their public behavior, have little real chance of getting the nomination and just aren’t treated very seriously as politicians. (I’m looking at you, Carson, Christie, and Fiorina.) It’ll be easy to get them to drop out. But convincing Romney that he won’t be the nominee is not a small thing, and it shows us just how powerful these insiders can be.

What Makes Us Politic? is Seth Masket’s weekly column on politics and policy.