As she releases a new memoir, the feminist writer and activist reflects on a career spent battling hostile online attackers — and having a little fun with them, too.

By Kastalia Medrano

Lindy West.

(Photo: Jenny Jimenez)

When the term “trolling” first came into vogue over a decade ago, it had a lighter, more impish connotation than it does today. Urban Dictionary defined it as “being a prick on the Internet because you can.” The iconic troll was an IMDb commenter, the kind who went on a Stanley Kubrick fan forum to champion another film director’s talents, according to the Irish Times. Trolling meant mischievous, good-natured provocation—something more along the lines of “messing with” than “tormenting.”

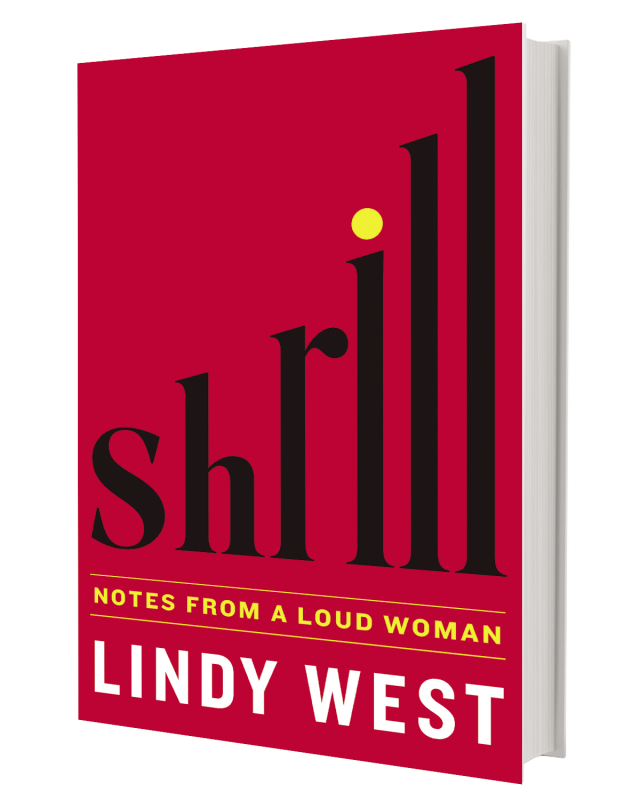

Now, of course, the term is associated with serious Internet harassment practices — including doxing and threats of rape and death. Lindy West, a Seattle-based feminist and author of a memoir released yesterday, Shrill: Notes From a Loud Woman, has been one of the loudest advocates against the ways that trolling has escalated online. In articles for the Guardian, Jezebel, and more, West has helped shape the working definition of modern trolling to mean recreational abuse against vulnerable people, especially women. West writes from personal experience: Trolling is, as West writes in Shrill, “a massive, multifarious online harassment campaign that has saturated my life for the past half decade.”

I don’t care about “feed the trolls” versus “don’t feed the trolls.” I care about me, and what makes me feel better.

Shrill captures a cultural moment when, West says, such misogyny is rampant, and “actively driving women off the Internet.” West’s book is not an essay collection, but it reads like one—each chapter tackles a variation on shame that Internet trolls encourage women to feel, including period-shaming, abortion-shaming, fat-shaming, slut-shaming, victim-shaming. West openly rebukes faceless trolls who target her and others, openly discussing taboo parts of female life — having periods, having sex, having abortions, and being fat — to blow open the silence that has dogged these topics and made them off-limits to women, both online and off.

Shrill is a fun book to read, full of punchy descriptors (West refers to the vagina, for instance, as a “shame canyon”), and lively personal anecdotes. It’s funny, but the prevalent humor doesn’t detract from the seriousness of the statement Shrill endeavors to make. Pacific Standard spoke to West last week about feminism, fat activism, and how the Internet has changed the way harassers shame women. This interview was conducted by phone.

Shrill reads like it couldn’t have existed in its current form even just a few years ago. There are a lots of all-caps, exclamation points, and “LOLs.”

I started planning the proposal probably five or six years ago, but it took a long time to figure out what I wanted to do. I finished the proposal about a year and a half ago and wrote [the book] in about nine months. I didn’t want it to feel like a book-length blog post, but the Internet vernacular has become a part of our everyday vernacular. I probably wouldn’t have written it like this even five years ago, but it’s so normalized now.

When did the Internet become so prone to the harassment of women? Do you think we’ve reached the peak yet?

I’d say it’s escalated in the last five years. That’s also hard for me to gauge because [five years ago was] when I started my transition from a regional writer to one with a national platform, so it’s possible that that’s just my personal experience. But it does feel that, in that time frame, online harassment has become incentivized. It’s like an organized sport at this point. That’s scary, but with that comes backlash, and there’s a lot of smart people trying to figure out solutions.

Shrill: Notes From a Loud Woman. (Photo: Hachette Books)

The only real solution is cultural change — teaching young men how to think about and communicate with women, for instance, and that women are not just a vessel for their catharsis, in a sexual way or in a way that relieves tension. That’s obviously a glacially slow process that most likely won’t end in my lifetime. In the meantime, there’s plenty of stop-gap measures I personally use, like block lists and auto-blockers, which clean up what you’re seeing. The trolls are still there, but they’re shouting into the void.

You interact with the trolls in your Twitter feed. What drives you to engage with them, rather than ignore them?

I respond a lot, but I also ignore the vast majority. The majority has already been preemptively blocked. I use the Google Chrome Blockchain extension, which helps me figure out who the ringleaders are, and block all of their followers. It’s great.

Sometimes, though, someone says something so absurd that it’s fun and cathartic for me to make fun of them. And it’s important to me that these people know that harassing me online is not a consequence-free hobby. I don’t want them to think they can just dump hate into my feed with no repercussions.

Also, I know there are a lot of women trying to survive online who don’t know how to cope with harassment, and who feel really anxious and alone about being on the receiving end of trolling. To whatever extent I can, I like to provide a model, and take the mystery and fear out of [responding]. I can get some horrible, ridiculous, contrarian, rude, cruel comment and make a joke out of it and dismiss it — I’ve heard from some people that that’s empowering.

I don’t care about “feed the trolls” versus “don’t feed the trolls.” I care about me, and what makes me feel better. And sometimes what makes me feel better is just making fun of some jackass. Oh, do they feel great because they got a rise out of me? Don’t care. They’re not my friend and I will never think about them again.

I try to be really careful to not just snap at people. Sometimes I’ll read an [insulting] tweet and be like, “What?” But I take time to make sure it means what I think it means. Sometimes it doesn’t, and I’m glad I didn’t just rattle off a response. Sometimes, someone says something horrifying and I come back with something sassy and it turns out they’re a 15-year-old kid and then I feel sad. Like, you need to stop doing this, kid, but also, I’m sorry.

In one chapter, you describe how you gained self-confidence in the last decade. At what point did you start writing off the haters?

I’m pretty impervious now. It was a gradual process. I was really traumatized for a long time, because it’s really hard. It’s really, really hard. There are different kinds of trolling. There’s really violent, scary, explicit death threats, which I don’t get that many of unless I’ve just written something controversial. But what’s almost worse is the mob trying to needle you — when you’re getting hundreds and hundreds of [messages .] You’re just exhausted and outnumbered and overwhelmed. There’s no recourse. If it’s 1,000 people each sending you one irritating message, you can’t report that.

I know how to deal with [this] now. I know I can get [some] accounts taken down. Twitter is better about this now. Me and a couple of other high-profile trolling recipients have got Twitter’s ear. I don’t know this for sure because it’s so opaque, but as far as I can tell there’s someone assigned to my case now because my reports get answered really fast. But that still leaves millions where we were before. [Twitter’s attention] makes my life better, but there are still tons and tons of women for whom that doesn’t fix the problem.

In a world without trolls, where you weren’t constantly defending yourself, what would you be writing about more?

I really miss writing jokes. I really love just writing humor. And I definitely miss writing about film and art and television and pop culture.

Your life gets so wrapped up in this storm of trolling because it’s overwhelming and it’s constant. You can’t ignore it because it infiltrates all of your communication avenues. It’s nothing but a deliberate distraction. Part of the mechanism is that [trolling] steals time from female writers and journalists who could be actually making change in the world.

I’d love for men to fix this problem. And yes, obviously, not all men [harass women online], but in my experience the vast majority who harass me are men, so it would be cool if men could be picking up some of the slack on fighting the online harassment problem. There are men who write about this [problem], but right now I see women spending so much time on trolls, and it’s just exhausting.

One of the things the book did rather nicely was address intersectional feminism without appropriating any experience that wasn’t yours. Do you often find yourself discussing how fat feminism varies from black feminism, gay feminism, and more?

All the people I really admire and think of as my closest colleagues, we talk about that all the time — navigating how to be an advocate without taking up space, without speaking authoritatively about other people’s struggles. That’s one of the most important cornerstones of my job. I have this platform, I have this [Guardian] column every week. I want to write about things that matter to me, but it’s hard to find a line between being an ally and an advocate, and co-opting someone else’s struggle and getting paid for it.

I’m constantly thinking about how to be a responsible feminist. What that entails is listening to other writers’ voices rather than writing my own thinkpiece about Beyoncé or whatever.

You have to take steps in your real life. You have to turn down jobs, you have to turn down money. I refuse to be on a panel if it’s only white women. I try to live my life and move my career forward with integrity. Someone asked me to re-contextualize The Matrix, knowing now that it was made by two trans women, and I said no. You should get a trans writer to write that piece, that’s not my piece to write.

In another chapter you write: “Please don’t forget — I am my body. When my body gets smaller it is still me. When it gets bigger, it is still me. There is not a thin woman inside me, awaiting excavation. I am one piece.” This seems different from the body-positivity narrative, which is something to the effect of, “I am not just a body, I am more than just my body.” When did you land on this feeling of “I am my body?”

I also agree with the other sentiment, and I’ve written about that, but they are two separate points.

I think that there’s a pervasive campaign to alienate women from our bodies, to get us to accept that our bodies are for the general public, which decides what size we should be, and what we should eat, and how much we should exercise. I want to push back against that.

[In the meantime], with fat people, you’re constantly told that it would be better if there was less of you. As though that’s not a personal thing to say. As though saying you need to get rid of 100 pounds of your flesh has nothing to do with you as a person. Of course it does.

I’m not just my body, but I’m also not just my “self.” I’m both.

You mention that there has been a shift in the public discourse around fat women over the last few years. What are the biggest changes occurring now?

When I started writing about this stuff, the prevailing ideas was that it was an abomination and absolutely unacceptable to be fat at all. Now it’s [only] a little bit better. You’re allowed to be fat, [but] you have to be in this constant state of apology and striving for “healthy” thinness, which isn’t that much better than before.

What I see right now is a lot of fat people and activists fighting for just the right to exist as we are. Fat people get into this [dilemma] of having to prove that their doctor said they’re healthy. But I don’t have to be healthy if I don’t want to be. Even just the idea that everyone should have to love their body — that’s a lot of pressure. I’m into dismantling external pressure and expectations that dictate who we are allowed to be, and what we’re allowed to put in our bodies. People can feel any way they want about their bodies.

The other major topic of conversation in the discourse around fat bodies right now is the gap between body acceptance and fat acceptance. You have Ashley Graham on the cover [of Sports Illustrated], and she’s beautiful, but she’s still conventionally attractive. Activists who are not plus-size models, who are making sacrifices, those are the people who really move the world and make space for all women to be able to exist.

As in, the body positive movement is a good step, but it’s not always as self-aware and inclusive as it could be to serve the people who need it most?

Exactly. It’s easy to declare yourself “body positive.” There’s no risk there. But, as in any social justice movement, it’s important to be aware of the people who are most affected and more oppressed when we’re having this conversation, and to not leave them behind.

||

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.