That’s both a good and bad thing.

By Jared Keller

(Photo: Chris Jackson/Getty Images)

Have you ever compulsively shared a viral Facebook post about why some distant stranger is voting for Hillary Clinton? Or marveled at your conservative aunt’s full-throated endorsement of Donald Trump because jet fuel can’t melt steel beams? Or spent hours arguing with some long-lost high school acquaintance over the overlooked merits of a Bernie Sanders presidency? Chances are all those hours wasted fighting people on social media weren’t actually wasted after all — they may have changed the course of the 2016 presidential election.

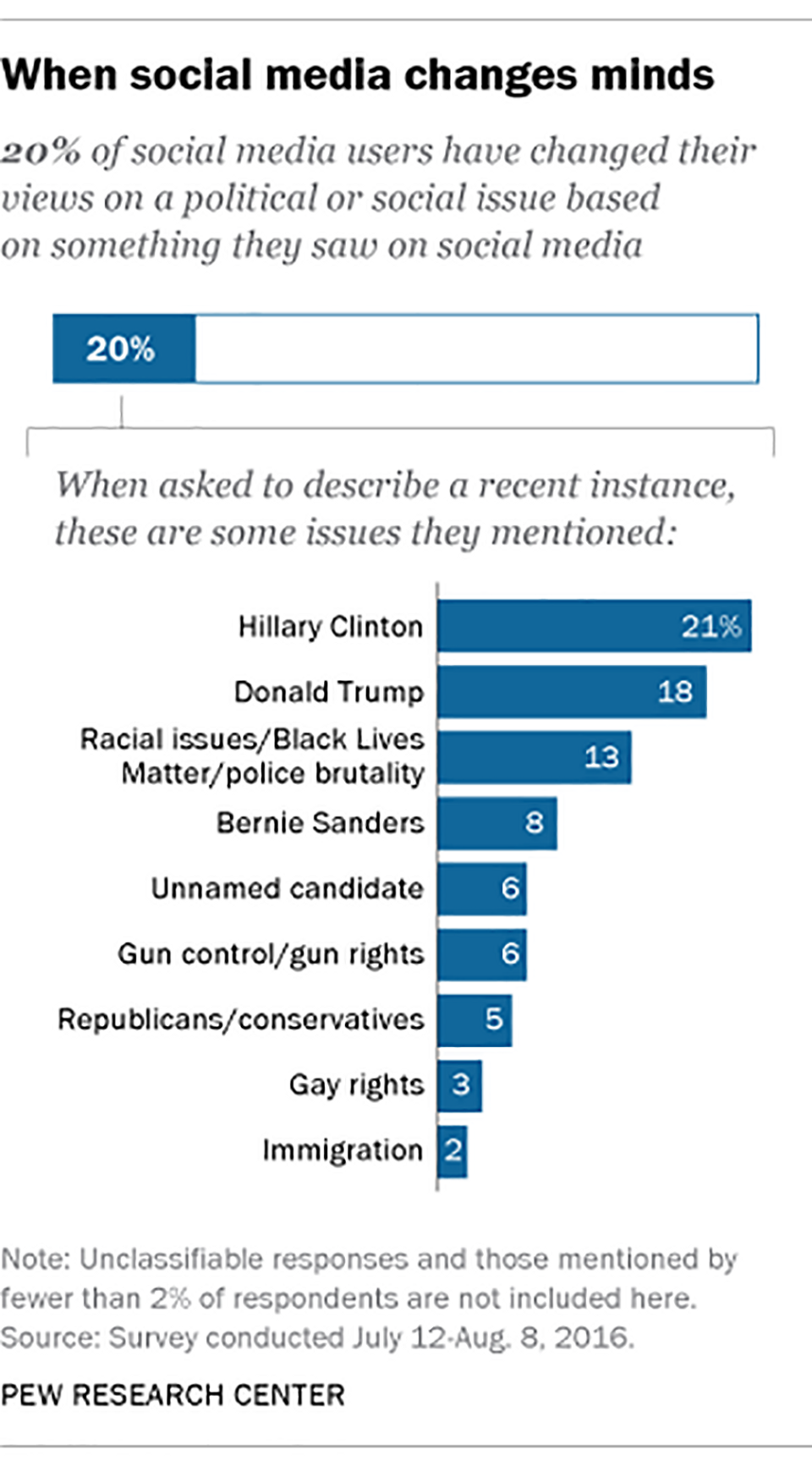

Well, not totally, but new analysis from the Pew Research Center suggests that our political interactions on the Internet may actually change the minds (and votes) of our Facebook-using polity. Some 20 percent of social media users told Pew they had “modified their stance on a social or political issue” thanks to a viral piece of content or Internet screed from a digital acquaintance; another 17 percent say social media “helped to change their views about a specific political candidate.” According to Pew, it’s liberal Democrats who are most susceptible to the transformative power of Facebook. Outside of Clinton and Trump, trending topics like racial issues (the Black Lives Matter movement in particular) and the Sanders campaign experienced the most social media-related change.

The commentary from the Pew survey respondents is a fascinating companion to the traditional man-on-the-street interviews that intersperse horse race campaign coverage. “Originally, I planned on voting for Hillary Clinton in the election, but then I found out about Bernie Sanders through social media. I decided I would vote for him instead,” one respondent wrote. “I thought Donald Trump was leaning one way on an issue and a friend posted something that was opposite of what I believe. This caused me to think less of him than I once I did,” wrote another.

Social media’s influence on electoral behavior has been long documented beyond the traditional acknowledgement of ideological segregation and digital partisanship. A study of data on Facebook and voter turnout during the 2010 mid-term elections found that users who issue “go vote!” calls to action featuring a friend’s face were more likely (by 2 percent, but still) to head to the polls, a testament to the power of “social influence” (and, as Rebecca Greenfield wrote at the time, shame) in nudging voters along. It’s the same effect as the real-life “I Voted” stickers that are ubiquitous at polling places. Facebook believes that the module was responsible for some 600,000 additional voters that year — enough to make a difference in a crucial swing state.

Facebook’s impact on voting behavior has likely grown along with the network itself. In the 2012 presidential contest, a 1 percent uptick in the youth vote — a major boon for Democrats, as usual — over 2008 turnout was partially attributed by researchers to the social contagion of the GOTV button that appeared at the top of millions of Facebook News Feeds. Still, it’s hard to quantify the impact of deliberate efforts.

“Most but not all adult Facebook users in the United States had some version of the voter megaphone placed on their pages. But for some, this button appeared only late in the afternoon,” wroteMicah Sifry in Mother Jones in the run-up to Election Day 2012. Some users reported clicking on the button but never seeing anything about their friends voting in their own feed. Facebook says more than nine million people clicked on the button on Election Day 2012. But, until now, the company had not disclosed what experiments it was conducting at the time.

(Chart: Pew Research Center)

This is the real significance of the Pew study: While we already knew that Facebook brings out voters, we now have a clearer sense of how those voters’ behavior changes at the ballot box. This should, in some sense, be a victory for Facebook and digital utopians in general. There’s now proof that the marketplace of ideas has created a vibrant forum for debating the biggest political and social issues of our time. Sure, Pew’s own data reveals that, while two-thirds of American adults use social media to express their political views, users overwhelmingly see political discussions on social media as “angry” (49 percent) as opposed to “respectful” (5 percent), “likely to come to a resolution” (5 percent) or “civil” (7 percent). But hey, passion is a good thing in a society that demands civic engagement, even if Bertrand Russell might disagree, right?

That all depends. Facebook could be a vital pillar of American republicanism — if Mark Zuckerberg can keep it. The company’s ongoing identity crisis — is it a neutral technology platform or a media company with an editorial stance? — has corrupted the fields of democratic exchange with a kudza of lies and misinformation. After firing the human editors who curate the ubiquitous “trending topics,” the social network repeatedly served up fake news stories to millions of potential voters. (That the editors themselves tended to lean liberal is itself problematic when you consider the network’s scope for obvious reasons.)

While establishment types fret the influence of Russia on the election, a few dozen teenagers in a single town in Macedonia are operating a network of pro-Trump sites that routinely dupe otherwise responsible voters. These stories aren’t just detrimental to an educated polity, but incredibly difficult to effectively debunk. “Yes, the info in the blogs is bad, false, and misleading,” one teen told BuzzFeed. “But the rationale is that ‘if it gets the people to click on it and engage, then use it.’”

The question of whether social media augments our democratic process has been answered. The next question, as New York Times media critic Jim Rutenberg observed last week with regard to fake news, is more complicated: What are we going to do about it?

If Pew’s data on the increasing influence of Facebook over electoral behavior is any indication, news organizations and companies like Facebook — not to mention voters — will require a new level of civic literacy in coming years. And, if the 2016 election cycle is any indication, that can’t come soon enough.