The (notably sarcastic) video above is an advertisement for Brownells, an Iowa gun accessory retailer that does much of its business online. Last fall the company, which describes itself, perhaps generously, as the “World’s Largest Supplier of Firearms Accessories and Gunsmithing Tools,” launched the video series as part of a sales and marketing campaign. The story focuses on a fictional Zombie Elimination Crew that uses Brownells-sold products to survive an undead apocalypse. After the video, clicking a link brings you to a photograph of the Z.E.C. and provides details of the survival gear each member uses. From there, you one-click to a purchasing screen, like any e-commerce site. For example, here’s the page for the zombie-branded rifle sight ($535) that one of the crew uses in the video. Similarly, the Zombie Hunter Kicklite Tactical Stock, which is an aftermarket butt for a shotgun, is engraved with the triple-arcing international “biohazard” symbol and the slogan “Zombie Hunter.” They also sell a Zombie Hunter upper receiver, a rifle part for the semi-automatic AR-15.

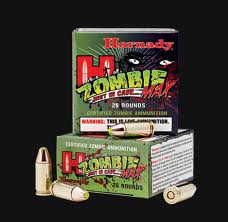

Brownells’ zombie campaign was part of a larger boom that began last year for zombie-themed weapons and accessories. Ammunition-maker Hornady found itself selling out boxes of its ZombieMax brand bullets. ZombieMax also has a monster-movie-inspired web video advertisement, to sell real bullets for real guns.

Responding to the trend, Guns and Ammo magazine launched a special edition, Zombie Nation, last summer. Zombie Nation‘s cover story was about an AR-15 assault rifle painted in radioactive green, outfitted with add-ons to allow automatic operation that “bridges the firepower gap between a rifle and a machine gun.” So-called “slidefire” modifications would be necessary for killing waves of zombies, goes the marketing message; the joke had already caught on with rapid-fire rifle enthusiasts:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=za59uquYEEQ

None of this was particularly mainstream, and private companies like Brownells and Hornady (whom we also contacted, and who did not respond to messages) are not required to release sales figures. But the market seemed to grow through last year. Hornady, Brownells, and larger dealers like Cheaper Than Dirt responded to growing demand by expanding their lines of zombie products. (Here’s Cheaper Than Dirt’s 3D Bleeding Nazi Zombie Target, $79.95, for example).

By mid-2012 zombie gun vogue had grown sufficiently to support theme events. Live-fire zombie shoots sprouted up. These were sport shooting events where you could dress as a zombie hunter and navigate a shooting course designed to simulate the apocalypse. Less popular than zombie pub crawls peaking around the same time, the undead shoot-ups attracted crowds that were small enough to fly under the national radar, but large enough to make it worth an organizer’s while. One event drew 1,200 in Minnesota. Sponsors at a Nebraska zombie shoot, Pandemic 2012: Zombies in the Heartland, included the state’s Army National Guard.

Smaller players had gotten into the game. Florida gun parts dealer Spike’s Tactical marketed a zombie-themed trigger assembly for an AR-15 assault rifle, in which the “safety” selector has three settings, “Live,” “Dead,” and “Undead.” It’s currently on back order from nine to 12 months.

That’s typical. Cabela’s, another retailer with a well-known shooting accessories business, has trouble keeping zombie-branded bullets in stock. This year, when the post-Newtown national spike in gun sales came, the zombie trend went with it, catching a second wind.

A LOT OF THE MOST POPULAR zombie gun accessories are inexpensive. “Radioactive” cartridge boxes, or a $25 zombie handgrip for your pistol, are the little touches that dress up a gun rack without breaking the bank. Accessories: think of a good hat or the right earrings. In the case of Cabela’s, the famous hunting supplier mentioned above, it’s fair to say the stuff’s low cost might be the whole appeal: ZombieMax bullets are competitively priced, and stalking deer is an expensive hobby.

But most of the zombie gear isn’t marketed to hunters. It’s marketed to what the industry terms the “tactical” sector of the retail gun industry, which are companies that sell guns used for shooting people, not animals. Tactical weapons are also an accessory-heavy business, and it’s easy to paint a spare part zombie green and tack on five bucks. If you’ve spent time with shade tree auto mechanics, or people who like to build their own computers, or bicycles, you know the so-called “Tactical Ted” firearm customer. The zombie marketing fits an apolitical, purely sales niche: gearheads.

That complicates the discussion. Selling assault rifles with a toy-like campaign should be precisely the sort of industry behavior that helps gun-control advocates’ case. But the harder you look at the marketing, the further in on the joke you get. The professionally produced Z.E.C. videos are closer to something from The Onion Video Network than to any “prepper” stereotype. Borrowing from mainstream marketing, they’re gently mocking their own customers, who obsessively collect soldierly accessories, modify the weapons and do their own gunsmithing. The actors playing the Z.E.C. (who appear to be members of Brownells’ staff) carry off the seriousness of their fictional mission with impressive deadpan. When one goes down injured—he slips in a puddle—a chunky teammate gambols inelegantly to his rescue and “tags in,” professional-wrestling-style. Paranoids in a mountain cabin, this isn’t. If it were an ad for soda or cell phones you’d call the tone ironic distance.

The difference is that no one is trying to ban cell phones. The zombie craze has also provided a new narrative for devices that dance on the edge of gun-law loopholes. The slidefire attachment, which gets as close to a U.S.-legal machine gun as one can, makes sense as a zombie-killing tool; it’s harder to justify in non-fantasy settings.

In mid-2012, Kentucky gunmaker Doublestar built the “Zombie X,” a modified Kalashnikov assault rifle. It had a high-capacity magazine, a bag for storing severed limbs, and a working chain saw mounted to its barrel. Designed as a publicity stunt for a trade show, the one-off design got so much attention, Doublestar founded a subsidiary to put the chain saw attachment into retail production.

The company “intended the Zombie X Chainsaw Bayonet to just be a promotional item for the show, just to attract attention to our booth,” explains Doublestar’s statement on the accessory. “But after such an overwhelming acceptance and bravado, we could see by the second day, that we were going to have to manufacture them.” It formed Panacea X LLC, a Nevada organized limited liability company, in March of 2012, primarily to bring the Zombie X Chainsaw ($498) to market.

“I GUARANTEE YOU, a lot of people from where I grew up were asking themselves this practical question,” Bill Clinton told Democratic lawmakers in a widely reported strategy talk a week ago, “If that young man had had to load three times as often as he did, would all those children have been killed?”

Clinton’s admonishment to his party argued that a post-Newtown gun control debate doesn’t necessarily have to cleave the country in two. How, though, to reconcile Clinton’s argument with the Zombie-X: a weapon so over-the-top, it is hard not to read it as a political act, more than as a product with a profit motive. Like speaking crassly to test First Amendment limits, or staging a sit-in to prove the 14th’s, a working tactical rifle designed to fight fantasy monsters is a statement of intentions: “As long as I don’t hurt anyone, I have a right to do this.”

But why zombies? Is it just because a machine gun—more than a brand of soda, or a smartphone—really would be useful against them? Writing a few years ago at Slate, Torie Bosch chalked up the non gun-world’s zombie fascination and hit TV shows like The Walking Dead to the tamer roots of white-collar anxiety:

These highbrow zombie stories are not just about watching the newly humbled struggle to make sense of the topsy-turvy world. The suburbanite/urbanite viewer who can’t hunt, can’t slaughter animals, can’t grow her own food, is meant to shudder at her ill-preparedness while watching. It’s the existential fear of the economy writ large: I sometimes wonder what I would do if I lost everything. Move in with my mother? Crash on a generous friend’s couch? Somehow put my supercharged typing skills to use? The zombie apocalypse scenario takes these fears and explodes them.

Perhaps—but she didn’t mention the zombie guns, which had yet to really become a craze by then. More recently, the “alternative right” writer Jack Donovan, “an advocate for the resurgence of tribalism and manly virtue,” did. Donovan, an obscure novelist whose blog gives off a bit of a Robert Bly-as-a-Skinhead vibe, is one of the few to ponder the zombie gun market specifically:

Prepping for the Zompocalypse gives the more adventurous folks on your cul-de-sac a way to dip their big toes into a kiddie pool of tribalism and get used to the feel, texture and temperature of blood. It allows them to work through primal gang survival scenarios using live ammo without looking like psychos. …

… Zombies are socially acceptable substitutes for the people we’re afraid of, the people we worry we might have to kill if we don’t want to be killed. Zombies are stand-ins for violent “youths,” for the hungry poor, for criminals and gangs and the people out there who want to break into your house and take your stuff.

If Bosch is right, and the zombie craze is about middle class anxiety, then the slime-green guns really are just a marketing joke, albeit in a cynical industry. It would mean the zombie shoots really are fundamentally just gun culture Comic-Con, and probably no more or less encouraging of tragedy than anything else. It’s a day at the range with your as-yet legal weapon, playing dress-up.

If Donovan’s closer—and we’re hesitant to grant him too much credit; the rest of his post is a good deal uglier and he failed to reply to a note—then the fact of real weapons sold as fantasy props isn’t so benign. In that case, it would mean the rest of one’s getup is the costume, and the zombie rig is the real clothes, and the person wearing them thinks zombies are real.

Metaphorically. But real. And coming.

In that case, the client base for zombie assault rifle gear would be a culture worth further study by anthropologists, not journalists. It’s a culture in which someone who thinks the rest of us are zombies could find a home. And may feel the need to defend it.

The Pandemic 2013 zombie shoot, a repeat of 2012’s successful event, is scheduled for May 31 – June 2. It will be in Grand Island, Nebraska.