“How do I get to the synagogue?”

A woman steps into a candy-green shop in Mattancherry, a neighborhood known around here as “Jew Town.” Outside, the street bustles with tourists and sellers arguing over the prices of pashmina scarves and harem pants. But inside, the newcomer, Aviva Kelly, an Israeli-American woman visiting from D.C., takes off her glasses to admire colorful items for sale including sparkly kippahs, multi-colored challah covers, and gold menorahs. Once inside, she seems to forget she’s headed for Paradesi Synagogue. “Who takes care of this shop?” she asks.

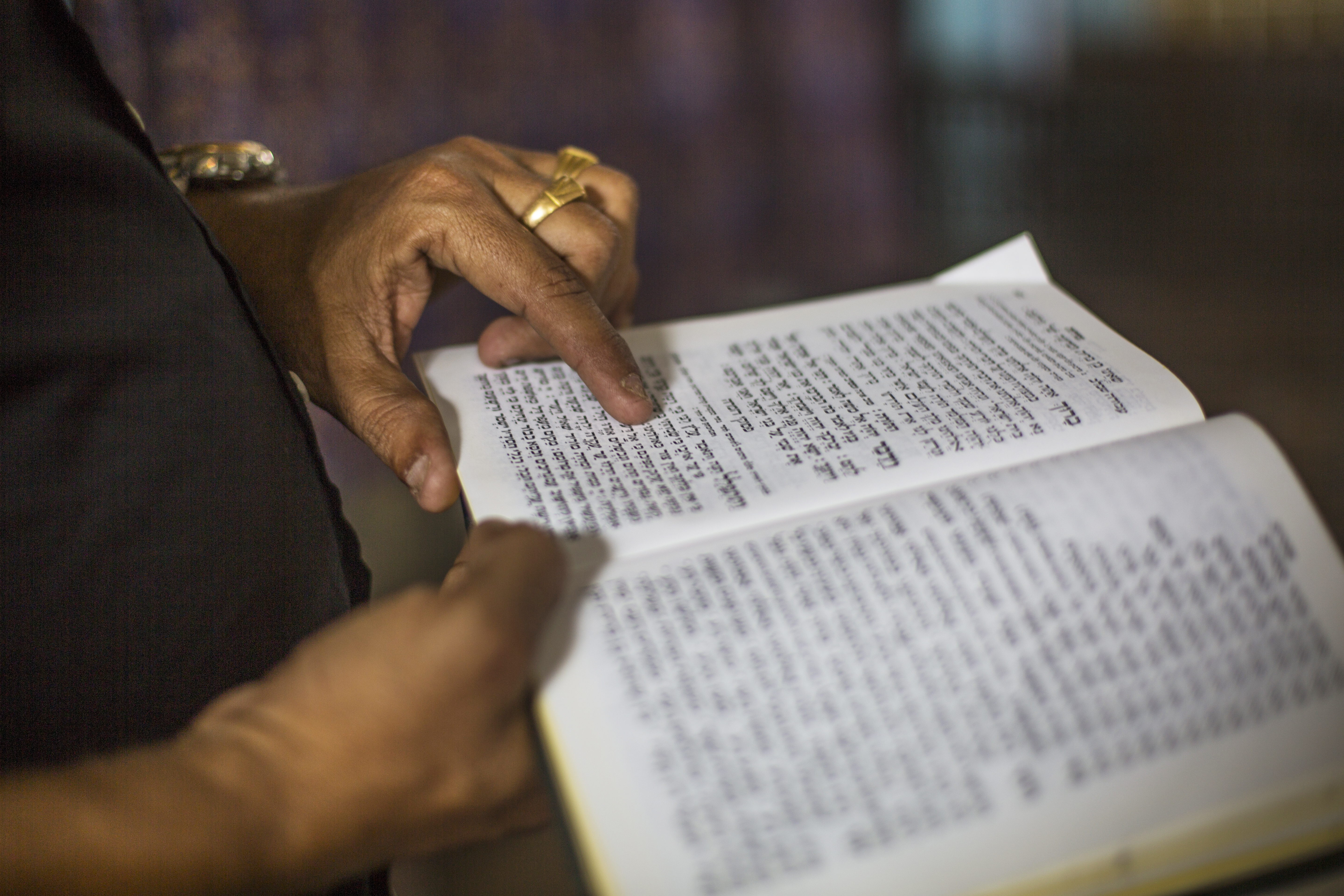

The cashier leads her into an adjacent room where old black-and-white photos hang on faded yellow walls. There, Sarah Cohen, 95, sits with prayer book open, her late husband’s hot-pink kippah perched on her head. The women introduce themselves, and soon decide to sing a prayer together in Hebrew.

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

“Your tune is slightly wrong,” Sarah says shortly after they begin. Aviva laughs, insisting she knows the Iraqi version of the tune. Sarah seems skeptical, but after they reprise the song, she begins grinning widely, clearly satisfied.

Cohen is one of five Paradesi Jews left in Mattancherry, a colorful neighborhood in India’s coastal city of Cochin, located in the southern state of Kerala. She opened this business—an embroidery shop—out of her home in 1984. Soon after it opened, she invited Jews and non-Jews alike to sing and learn about Jewish heritage from her, and over time it became a hub of Jewish culture in the community. Today, her shop is one of the only traces of Judaism left in the area.

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

Cochin, a majority Hindu and Christian city, has a rich history of Judaism. Historical accounts hold that Malabari Jews came to Kerala in the 11th century B.C.E., while Paradesi Jews arrived from Europe in the late 16th century. But when Israel and India gained independence in the 1950s, most of the Indian Jewish population migrated to Israel. Now, only 28 Jews remain in Cochin, scattered and holding onto their traditions as a minority religion.

Nevertheless, their longtime peaceful co-existence with the Hindus, Muslims, and Christians of Kochi continues to resonate. “It is from the history of Jewish people in Kerala that we understand religious tolerance,” says Karma Chandran, a retired history and government professor at C. Achutha Menon Government College. Upon arriving in Kerala, Jewish refugees were given land and materials from the local government to construct synagogues. “Inter-religious cooperation is seen more here than anywhere else in India,” Chandran says.

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

Cohen’s home exemplifies the religious synergy that has come to characterize her neighborhood. Her caretaker who now runs the shop, Thaha Ibrahim, is Muslim, and her cook, Celine Xavier, is Catholic.

“The Jewish tradition is special to Cochin,” Ibrahim says. “Many communities came together in Kerala for trade. That supporting culture is felt everywhere. We are all just people.”

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

Across the Kollam-Kottapuram Waterway in Ernakulam, the commercial hub of Cochin, Josephai “Babu” Elias, 62, shuffles among bird cages to serve a customer. Babu takes care of the Kavumbhagam Synagogue on Ernakulam’s own buzzing “Jew Street”; at the front of the building he also runs a plant and fish nursery. Upon entering the synagogue, one can see both fish swimming in neon-blue tanks and, just beyond, a glittering prayer hall lit by pink chandeliers—a surreal, striking entrance for a place of worship.

Elias laughs when I ask if people are surprised to see tanks of fish abutting a Jewish synagogue. “Fish are Jewish!” he exclaims, referring to the significance of fish in the Jewish tradition. “In biblical times, fish meant prosperity, so it kind of makes sense.”

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

A Malabari Jew, Elias says that, when his family left for Israel in the ’70s, he stayed behind to watch over the synagogue. He remembers his childhood fondly: “More than 150 people filled the synagogue. I was the last of my family to feel the identity of the community. Rituals, prayers, and ceremonies keep the community together. When there’s no community, these fall apart.” The diminishing Jewish community in Cochin rarely gets together even for events, Babu and his wife say. Babu adds that he finds himself praying alone in the synagogue every Friday.

Babu hopes to hand over the synagogue to an international trust in the next couple of years, and then migrate with his wife to Israel, where his daughter already lives. “Leaving India is unbearable,” he says, “but it is inevitable because every Jew believes the last days of his life shall be in Israel.”

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

(Photo: Rachel Reed)

But first, he is overseeing synagogue renovations. He re-tiled the floor in May, and, next, he hopes to install new oil lamps and chandeliers.

“It is Indian responsibility to protect Jewish monuments,” Karma, a Hindu, tells me. “Tolerance has a history, tolerance has a tradition, tolerance has a heritage. It’s the heritage of Hindus, Muslims, and Christians: the monuments are Jewish but it’s everyone’s heritage. Once it’s preserved it can be an example for the rest of the world.”

(Photo: Rachel Reed)