Officer Richard Walter looked out the window of his patrol car and saw two young men trading punches outside Sutter’s Saloon.

It was 2 a.m. on what should have been a forgettable night shift in 1989. Sutter’s was near the State University of New York at Buffalo—a student hangout, not a rough dive. Walter, now a seasoned detective, still can’t shake the bizarre and bloody memory of that night.

The men didn’t notice the cop pull into the parking lot. Walter grabbed his baton and approached, then saw a glint of metal. One of the men held a knife, the blade protruding three inches from his clenched fist.

Instantly a geyser of blood spurted from the unarmed man’s neck onto Walter’s uniform—10 feet away. The man collapsed, his neck slashed open “from his ear to his Adam’s apple,” Walter said, recalling what he wrote in the police report. Blood pulsed onto the pavement from his severed carotid artery and jugular vein.

Walter drew his gun and pointed it. The attacker dropped the knife and clasped his hands around his victim’s gashed neck to stanch the bleeding.

“I’m a medical student,” the attacker said. “I know what I’m doing.”

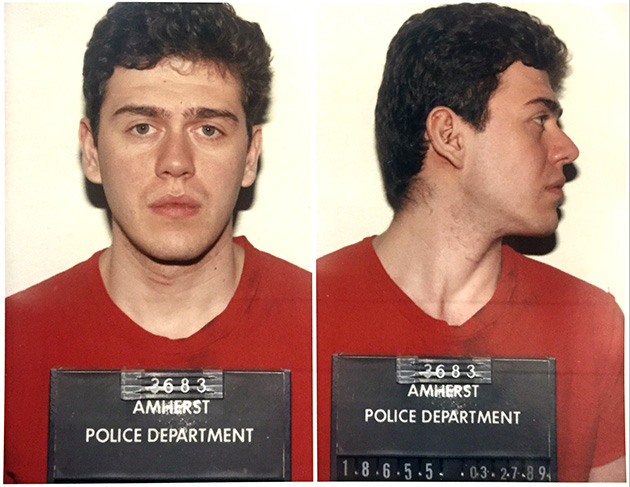

Twenty-five years later, Dr. Constantine Toumbis sat at a large conference table at Citrus Memorial Hospital in Central Florida. On the night he was arrested outside Sutter’s Saloon, his clothes and hair were splattered with blood. At the board meeting in August 2014, he wears a dark tailored suit, a crisply knotted tie, a monogrammed shirt and cuff links. His salt-and-pepper hair was neatly cropped. He jotted notes with an elegant pen.

By many measures, Toumbis’ career is a success. He’s been chief of staff at Citrus and sits on its board of trustees. He is among Florida’s busiest spinal surgeons, operating at Citrus in Inverness and also at Seven Rivers Regional Medical Center in nearby Crystal River. He earned $1.2 million just from Medicare in 2012.

But when ProPublica compared the performance of nearly 17,000 surgeons who do elective operations under Medicare, Toumbis stood out for another reason: His complication rates for routine spinal procedures were among the highest in the nation. At least two of his patients died and 44 were re-admitted to the hospital with post-operative complications over five years.

When we traveled to Florida to find out more, we interviewed someone who knew Toumbis and mentioned hearing he had once been convicted of a violent crime. A Google search turned up a story from the Buffalo News headlined “Former Medical Student Gets Public Service Term.’’ It set out how Toumbis had stabbed a classmate and been found guilty of felony assault.

While Toumbis’ criminal record was not relevant to our examination of surgical complications, it did raise questions about systems for licensing and vetting doctors.

Doctors applying for state medical licenses and jobs are typically asked to disclose any criminal convictions. Records show that Toumbis omitted or misrepresented his crime and felony record when he applied for a hospital internship and in filings submitted to Florida medical regulators. In one of those records, he even portrayed himself as a victim—of an attacker who thrust his neck onto Toumbis’ dagger.

It’s unclear if both of the hospitals where Toumbis operates are aware of his past.

Citrus Memorial did not respond to questions about Toumbis’ criminal history.

Ryan Beaty, the hospital’s chief executive for about 10 years until he retired in 2014, said he didn’t know about Toumbis’ felony conviction until ProPublica told him about it. “He just doesn’t seem like that kind of guy to me,” Beaty said. “It also surprises me that I didn’t know. Somehow I missed that bit of information.”

Seven Rivers officials said Toumbis disclosed his felony conviction to them. “Dr. Toumbis further shared his unwavering determination to fulfill his career goal to become an orthopedic surgeon despite this unfortunate incident that interrupted his lifelong ambition,” Dorothy Pernu, the hospital’s director of marketing and communications, said in an email.

Toumbis, 49, declined multiple requests to answer questions about his record.

In May, a ProPublica reporter visited Toumbis’ office and left a note. Toumbis did not reply, but a Citrus County sheriff’s deputy called to say Toumbis did not want to be contacted. A week later, a notice arrived from Toumbis warning that future visits would be prosecuted as trespassing.

It began with a dispute about karate.

When Toumbis was about 12, he helped a teenage karate instructor put on demonstrations for Cub Scouts. As a reward, he received what he would eventually acknowledge in a medical school hearing was an “honorary” black belt. He acknowledged “puffing” up his medical school application by saying he was a karate instructor. He also told friends he was a black belt in the martial art.

In fact, Toumbis worried about defending himself. While an undergraduate at New York University, he bought a knife to ward off any threats. Called an Urban Skinner, it was a push dagger—designed to be held in a fist with a three-inch blade protruding outward.

Toumbis didn’t get into medical school on his first try, so he went to the SUNY at Buffalo, commonly known as University of Buffalo, for a master’s degree in natural science. There he befriended the student who would become his victim, Frank Slazyk. The two earned their degrees together, then entered the university’s medical school.

Toumbis and Slazyk socialized with the same group and studied in Toumbis’ apartment. That’s how Slazyk saw Toumbis’ black belt, which he believed to be real, and heard Toumbis’ claim that he was a karate instructor, which he believed to be true.

On Easter Sunday, March 26, 1989, Slazyk invited Toumbis to celebrate with pierogi and Polish sausage at his grandmother’s house. Toumbis couldn’t make it, so that night they went to a bar to play darts, eat chicken wings, and drink beer.

According to the bartender’s statement to the police, Slazyk and Toumbis had been having a good time but got unruly late in the night. Slazyk was making karate motions and feigning punches and kicks at Toumbis, who was blocking the blows and coming back with some of his own shadow-boxing moves.

The horsing around got rowdy enough that the bartender asked them to leave, and the two walked out together. There didn’t seem to be any actual hostility between them, the bartender said. Another person at the bar told police Slazyk had apologized to Toumbis before they left.

Toumbis later claimed at his trial that Slazyk was goading him into a fight at the bar, saying, “Let’s see some of your karate.” Toumbis said that after a few blows made contact and it got heated, the bartender agreed to delay Slazyk so Toumbis could leave first. Slazyk followed and attacked him in the parking lot, Toumbis said.

Slazyk told ProPublica in an interview that Toumbis lost his temper when he saw that Slazyk hadn’t locked his car door. He said they were arguing about the door when Toumbis said, “Don’t get lippy with me. I have a black belt.”

That’s when Slazyk said the brawl began.

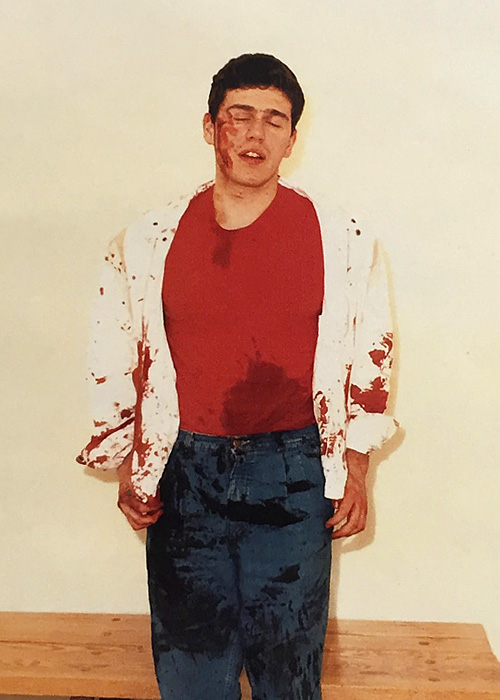

When other officers joined Walter outside Sutters’ Saloon, they found Toumbis trying to stop Slazyk’s hemorrhaging. His white canvas jacket and face were smeared with Slazyk’s blood.

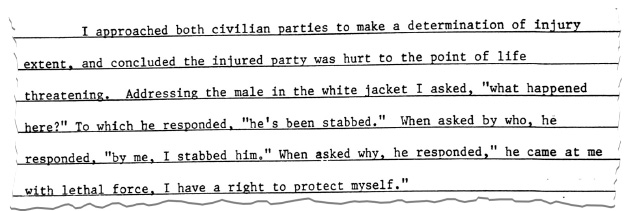

“What happened here?” one of the cops asked.

“He’s been stabbed,” Toumbis said, according to a police report. “By me. I stabbed him. He came at me with lethal force. I have a right to protect myself.”

In subsequent accounts, however—before a medical school committee and when he applied for his hospital internship and Florida medical license—Toumbis would not admit to stabbing Slazyk. His versions of the incident would include details that were inaccurate or contradicted by other witnesses.

About two weeks after the stabbing, a committee of professors from the University at Buffalo medical school met to determine whether the two students should be expelled. According to a transcript of the meeting, Toumbis told the panel the Urban Skinner was a hunting knife he had bought at the nearby Boulevard Mall.

“It was not purchased for self-defense,” Toumbis said. “I didn’t think of it as a weapon.”

That clashes with Toumbis’ testimony under oath during his trial more than a year later, when he said he bought the knife in New York City to frighten off would-be attackers.

Toumbis told the medical school committee that he pulled the knife to scare Slazyk, but that his friend “moved his neck in the way” and “rushed into it,” according to the meeting transcript.

Toumbis argued that he should be allowed to continue his studies because it was a tragic accident. He added that he saved Slazyk’s life by stopping the bleeding.

The medical school expelled Toumbis. He enrolled in a doctoral program at the same university and obtained a Ph.D. in experimental pathology in 1993. The school declined to comment for this story.

At his two-week trial in November 1990, Toumbis testified that he had intended to scare Slazyk, held the knife in front of him and said, “Stay the hell away from me.” Walter, the police officer who witnessed the stabbing, testified that he did not hear Toumbis say anything to Slazyk before he stabbed him.

Toumbis testified that he never intended any harm and that he would have to live the rest of his life knowing that “the instrument that I held in my hand was the cause of almost taking a life.”

The jury convicted Toumbis of second-degree assault, which New York State law defines as recklessly causing serious physical injury to another person with a deadly weapon.

Toumbis called several character witnesses who pleaded with the judge not to send him to prison. His mother, Evelyn Toumbis, sent a letter saying the health of her husband began deteriorating the day of their son’s arrest. The dream Toumbis’ father had of his son becoming a doctor had “suddenly vanished.”

“I can say to you honestly, Judge Drury, that my husband died of a broken heart,” Evelyn Toumbis wrote.

At the sentencing hearing, the judge chastised Toumbis for not being truthful about the stabbing. The Urban Skinner dagger he used to cut Slazyk’s throat was not a hunting knife upon which Slazyk had accidentally been impaled. “It’s a vicious street weapon” the judge said.

He added: “You impaled yourself on this—on your own testimony and led to your conviction.”

Toumbis was sentenced to probation and 2,000 hours of community service.

Toumbis was accepted into the Wayne State University Medical School in Detroit in 1994. Documents on file in Florida show that an official at Wayne State later told the Florida Department of Health that the school reviewed “the incident at Buffalo,” spoke to the judge and interviewed Toumbis before deciding “that he would make a good physician.”

In May 1998, Toumbis applied for a surgical internship at the University of Florida Health Science Center in Jacksonville, according to documents on file with the Florida Department of Health.

The application asked if he had ever been convicted of a felony. In the sworn statement, Toumbis answered “No.” He was accepted into the internship program.

On the application for his United States Medical Licensing Examination, Toumbis was asked to list all medical schools he had attended, “whether completed, or not.” He did not list the University of Buffalo Medical School, which had expelled him.

Toumbis did acknowledge a felony conviction and medical school expulsion on his Florida medical license application. The statement he attached casts the stabbing as a matter of self-defense.

The statement says he went for a late-night snack at a restaurant and encountered another medical student who became hostile and aggressive. Toumbis alleged he asked a restaurant employee to detain the student, but as Toumbis went to his car, the statement says, the student threatened him.

“In an effort to deter any further aggression, I displayed a small knife which I legally possessed,” Toumbis wrote in the statement. “Undeterred, my assailant lunged at me and was cut. Bearing no personal animus against my attacker, I immediately rendered first aid.”

Elsewhere in the statement, Toumbis describes the Urban Skinner as a “pocket knife.”

Mara Burger, a spokeswoman with the Florida Department of Health, confirmed that Toumbis did not disclose his felony on his internship application, and that his U.S. medical licensing exam application did not list the medical school that expelled him.

Whether the committee that approved his license noticed the discrepancies is unknown, she said. Although the department reviewed the court documents Toumbis provided when he applied for his license, it did not do any further investigation to determine the nature of the crime, she said.

The state’s file contains several recommendations from Toumbis’ supporters. A professor from SUNY Buffalo praised Toumbis for his diligence, hard work, intellectual excellence and medical competence. “I believe he is of good character and well motivated to combine research, teaching and clinical service in academic medicine.”

But Dr. J.J. Tepas III, director of the general surgery residency program at the University of Florida Health Science Center, rated Toumbis low on most of the categories measured: medical knowledge, teaching ability, fitness for clinical practice, motivation, initiative, responsibility and integrity. Tepas declined to comment for this story.

In a follow-up letter, Tepas re-iterated his negative assessment, saying he had observed Toumbis in practice on many occasions. “I have been consistently impressed by his obvious lack of interest in some of the very basic tenets of bedside clinical care,” Tepas wrote.

In his trailer home near Buffalo in August, Slazyk, 51, sat at the kitchen table drinking coffee and chain smoking Seneca cigarettes. There’s no missing the faded, jagged lines of the scar on his neck.

Slazyk’s left eyelid permanently droops—a result of a stroke from losing so much blood the night he was stabbed, he said. Words come out raspy because his voice box was torn.

Slazyk had grown up in a poor neighborhood of Buffalo called Black Rock. Medical school was supposed to be his ticket out. His dream was to become a surgeon specializing in cancers affecting women, he said.

But Slazyk never really recovered from the stabbing. He went back to medical school but was too traumatized to continue. That contributed to the alcoholism that sent him into a tailspin, he said.

The stabbing “knocked me off the track” in medical school, Slazyk said. “I was doing fine until then. Then after that, even being the victim, they put me on leave for a year-and-a-half. I was punished.”

A couple of years ago, Slazyk learned that Toumbis had become a successful surgeon. He said he had an attorney contact him and they reached a confidential financial settlement.

Today, Slazyk does not work because of his manic depression and anxiety. His wife works as a housekeeper and he gets $730 a month in Social Security income. His medical school loans were expunged because of his disability, he said.

ProPublica made many attempts to speak to Toumbis.

After the Citrus Memorial meeting in August, a reporter approached him for an interview.

“Oh—little old me?” the surgeon said. “I don’t grant interviews. You’ll have to call the hospital public relations department.”

Walter, the cop who saw the stabbing, was stunned to find out that Toumbis is a prominent surgeon.

Recalling that night at Sutter’s, he said Toumbis chose to engage in the fight. One detail in particular stuck: Toumbis’ eyeglasses were folded and placed on the hood of the car, he said, which seemed inconsistent with portrayals of being attacked by Slazyk.

Walter told ProPublica that he did not see how Toumbis could justify the stabbing. Had he wanted, he could have run away or fled back into the bar.

“I’d just love to know how a guy who’s convicted of a crime like that can be a doctor,” Walter said.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “For a Surgeon With a History of Complications, a Felony Past” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.