What makes the video shocking isn’t just the violence; it’s also how rote the violence is. In the clip from October of 2015, Ben Fields—at the time, a sheriff’s deputy and the school resource officer at Spring Valley High School in Columbia, South Carolina—tells a young black woman to leave the classroom. She refuses. So Fields, who is white, wraps his forearm around the student’s neck, flips her—along with her desk—onto the floor, and tosses her several feet. He then handcuffs her with chilling casualness, as if this reflexive violence toward an alleged classroom disruptor is all in a day’s work.

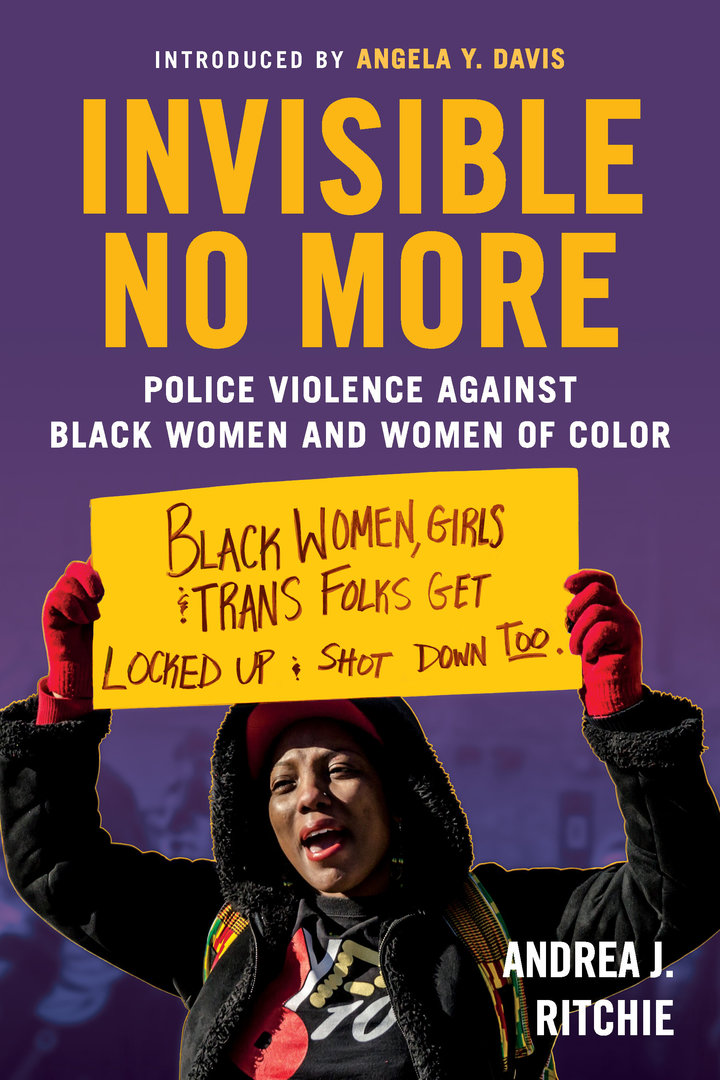

But, well, it is, in a way. And unthinking violence against black women shouldn’t be all that shocking, as Andrea J. Ritchie, a police-misconduct attorney, explains in her new book, Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color. What happened in Columbia—my hometown—was “representative of decades-long trends in policing black girls and girls of color across the country, in and out of school,” Ritchie writes. If this aggression comes as a surprise, it’s because—and this is exactly the author’s point—it wasn’t until recently that the issue of police misconduct against women of color found greater prominence in national discussions of a carceral regime run by police.

Seeking to end this historical erasure, Ritchie traces the patterns of abuse and violence against women of color and trans women by offering perspective from a long view. She begins her investigation in the colonial period, when “European colonizers seized and stole land by exterminating or relocating many of the 10 to 12 million indigenous inhabitants” of what would become the United States. The depth of Ritchie’s research is vast, and disturbing: for instance, she weaves together accounts that illustrate how, in the early 19th century, child-welfare authorities would regularly kidnap indigenous women’s children—for the ostensible purpose of assimilating these children into state-run or state-sponsored residential schools—and how “mothers who tried to resist their children’s kidnapping were subjected to violence, first at the hands of soldiers and later at the hands of Indian agents and police.”

Ritchie then puts this violence into the broader context of gender- and race-based hostility throughout American history. To wit: Once they were in the United States, African women had to endure exceptionally vicious forms of so-called “plantation justice,” which involved all kinds of brutal law enforcement in lieu of more expensive and time-intensive public prosecution. (Plantation justice could always be brutal, but it oppressed and punished black women in exceptionally cruel ways.) According to historian Gerda Lerner, whom Ritchie quotes, “punishment was meted out to [black women] regardless of motherhood, pregnancy, or physical infirmity. Their affection for their children was used as a deliberate means of tying them to their masters. … Additionally, the sexual exploitation and abuse of black women by white men”—essentially, institutionalized rape—”was a routine practice.” Ritchie’s examination of this history is sobering, as she unearths how law enforcement has, from the very start, cruelly flexed its power in ways that long went ignored.

(Photo: Beacon Press)

Yet Invisible No More hardly restricts itself to the past. Indeed, what makes the book so bracing isn’t just the central thesis, which might feel already familiar in the era of Black Lives Matter. Rather, the book’s central power lies in how it manages to highlight a full history of state violence aimed at women of color, and how indelibly that history informs present-day interactions with law enforcement. Ritchie, in turn, leads readers through America’s many “wars” with itself—including the war on drugs, broken-windows policing, immigration enforcement, and the war on terror—and how deeply they’ve affected women of color. Because what’s “deemed disorderly or lewd is often in the eye of the beholder,” for instance, police can sometimes unknowingly tap into racial and gender biases in their enforcement of laws.

As a result, Ritchie argues that the dominant law-enforcement paradigms have uniquely, and almost invariably, inflicted harm on women of color. She explains: “Whether a woman of color is read as a drug user, courier, or distributor, a disorderly person, an undesirable immigrant, a security threat, or some combination of these,” various policies have, over time, created a sort of “web of criminalization that ensnares women in devastating ways,” from being assaulted during a stop-and-frisk (a fraught practice) to being forced by cops into sexual acts to stave off arrest.

As I read Invisible No More, I thought of Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, a recent book by law professor and former public defender James Forman Jr. Forman’s own investigation of black history authoritatively establishes some of the tragic consequences—particularly on black men and on poor black communities—that resulted from the (often well-intentioned) policy decisions by black leaders in the latter half of the 20th century. Forman’s and Ritchie’s meticulous works complement one another, dissecting how marginalized communities have been ravaged by the powers that be—and, in turn, how they’ve resisted those assaults.

While there’s no clear path to an America without unjust policing, Ritchie ends her book on a hopeful note. “Each of us can contribute to the conversations, dreams, and visions we need to find the way,” she writes—to safe and affordable housing, to health care, to education, to living-wage employment, to childcare, to mental-health treatment. So: “Let’s get free.”