(Photo: Jack Herrera)

Two competing explanations exist for why over 2,000 migrants now live in a large, defunct nightclub in a poor southeastern corner of Tijuana, Mexico.

The first explanation is meteorological: When two large caravans of migrants from Central America first arrived into Tijuana last month, the Mexican government funneled them onto a large sports field on the northern side of the city. However, at the end of November, when rains came and flooded the field, the government closed the camp and moved migrants to “El Barretal,” an abandoned nightclub in the southeast of the city.

But many of the migrants (and the international aid workers working at El Barretal), disagree with that version of events.

“It’s bullshit,” Ángel, a 22-year-old man from Honduras, says when asked if the government moved the migrants because of the rain. Ángel sits, squinting in the sun, in the main courtyard of El Barretal, where over 1,000 migrants live in rudimentary tents on the pavement. “They just wanted to move us further from the border.”

James Cordero, a volunteer with Border Angels who works at the shelter, echoes that belief. “They moved the shelter here to make it harder for people to get to the border, where they can ask for asylum,” Cordero says.

El Barretal sits on the southeastern slope of Cerro Colorado, a hill that rises sharply in the middle of Tijuana. From El Barretal, the brown grass and rock of the mound block the view of the United States border, about 10 miles to the north.

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

Many believe this is the new shelter’s main characteristic: its distance from the border. Around the same time those fateful rains came to Tijuana, tensions exploded after photos of Customs and Border Patrol agents firing tear gas into a crowd of migrants went viral. (The migrants had broken off from a peaceful march to rush the border.) Many believe the Mexican officials, faced with enormous pressure to decrease tensions, opted to move the migrants 10 miles farther from the border, to El Barretal.

Outside El Barretal, a collection of enormous Mexican Marine vehicles sit idly near the entrance; about a dozen military members stand outside, chatting amicably. The official purpose of the soldiers is not to guard the door, but rather to operate an outdoor mess hall outside the shelter: The military-style kitchen serves residents of the shelter two meals a day, one at 9:00 a.m. and one at 4:00 p.m.

The sight inside the shelter might surprise one whose idea of “refugee camp” conjures images of the uniform white tents of the United Nations. The majority of the migrants in the camp (which, in a point of legal terminology, is not technically a refugee camp) live in rudimentary tents and tarps in an outdoor “patio,” a concrete-covered courtyard just inside the entrance. Winter in Tijuana means the days stay relatively cool. Nights, however, often drop into the low 40s, and many migrants in the camp, especially those with children, speak of a difficult cold. Maria, a mother of two from El Salvador, says she can hear children around her tent having asthma attacks each night when the temperature drops.

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

Respiratory illnesses are the most common ailment affecting migrants, according to Oscar Ginera Aparicio, the state director of health services in Tijuana. Many of the migrants in the camp, even the teenagers, speak with the gravely voices of chainsmokers; in reality, the husky accents likely comes from weeks of living in cold and dusty conditions.

Besides respiratory illnesses, Aparicio cites skin ailments such as allergies, rashes, and lesions as the most prevalent health concern. Many in the camp also have visible parasites living in their hair; one of the most coveted donations to arrive here is a lice comb.

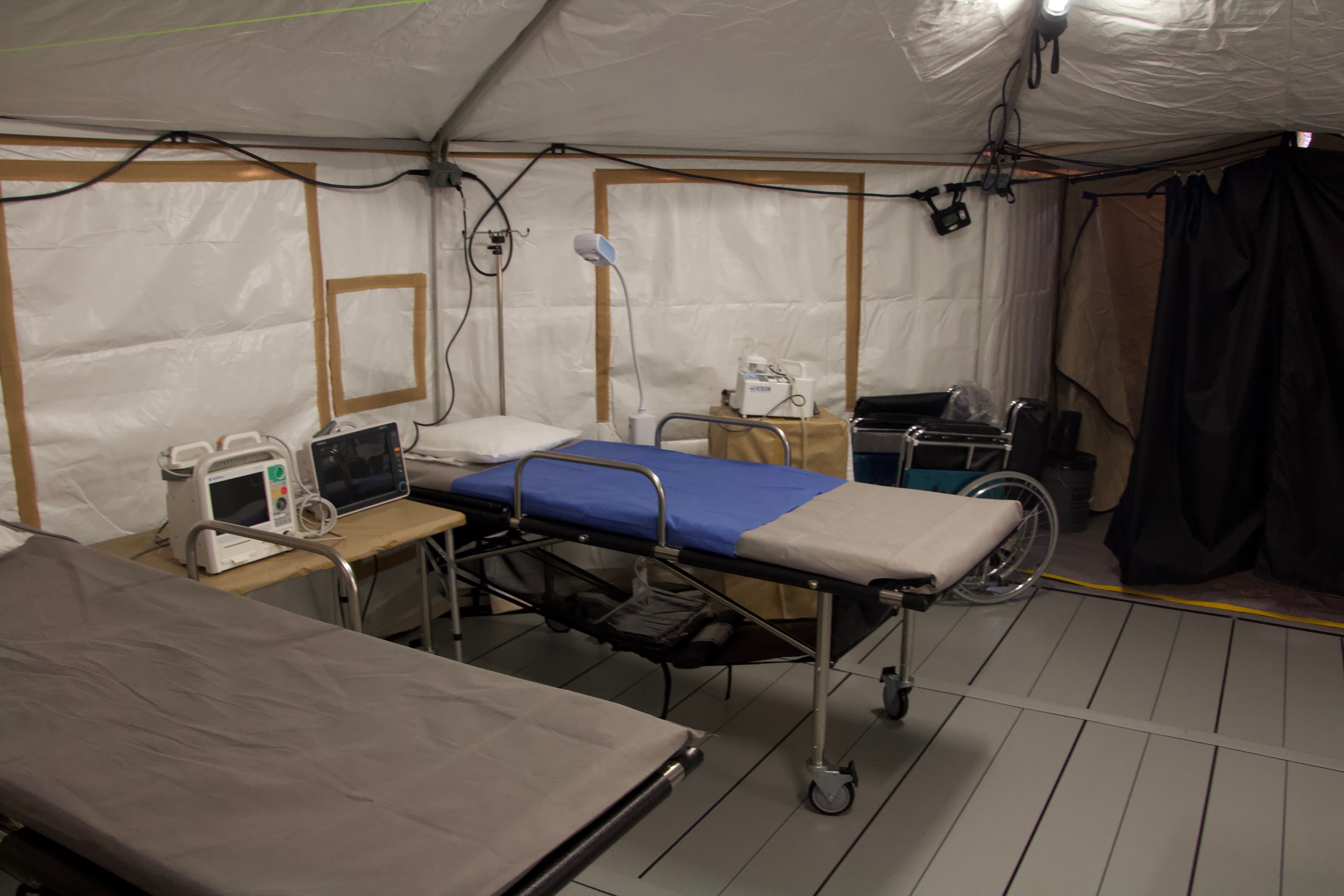

The Mexican government runs a health clinic within the shelter. This includes a mobile dental office, where government-funded dentists provide both restorative and preventive care. Nearby, two large tents have been connected to form a field hospital. Inside, a series of cots host patients whom the doctors in the camp have determined need extra surveillance: Some of these patients are people experiencing epilepsy symptoms, or concussions. The doctors also monitor and test people showing symptoms of what could be infectious diseases. Though they’ve tested patients for influenza and tuberculosis, Ginera says they’ve found zero cases of these illnesses so far. However, four people in the camp—three children and an adult—have chicken pox. Though Ginera said they’d been quarantined, a doctor at the camp said that the children were all living with their own families; they’d been given face masks, and instructed to stay in their own tents.

Ginera also says that over 40 migrants who arrived with the caravan were pregnant. Most are in their first or second trimester, but some of the women in El Barretal are seven- or eight-months pregnant. It’s likely they will give birth while living in the camp.

For parents who already have children, a portion of El Barretal has been cordoned off as a dedicated child and family space. This area includes all the indoor space in El Barretal, and a small courtyard where the United Nations Child Emergency Fund runs a “children’s pavilion.” Here, in a large white tent, UNICEF provides children with both medical and psychological services.

The bathrooms in El Barretal are rudimentary. Many of the rooms that contained toilets for the nightclub are no longer operating; some migrants live in these defunct bathrooms. For services, a long row of portable toilets lines a wall in the main courtyard. The insides are generally unclean, but they are serviced regularly.

For bathing, the four “baths” most of the migrants use are actually a row of sinks inside one of the nightclub’s bathrooms. In this bathroom, where the floor is often flooded with soapy water, people wash both their bodies and their clothes. In the private courtyard where the U.N. maintains its child and family area, there are makeshift outdoor shower stalls made of plywood and PVC.

“This is a fully functioning refugee camp. But it is still a refugee camp,” says Estafania Rebellon, a volunteer working in the camp. Rebellon says she admires the work being done by volunteers, members of the U.N., and the Mexican government. She says she sees things “both ways”: Yes, there could be more and better services available to migrants. “But there’s a lot of good work being done here; the camp is operating,” she says.

Below, more photos of life inside El Barretal:

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)

(Photo: Jack Herrera)