Mahmoud Harmoush is one of a handful of students participating in Claremont School of Theology’s new partnership with the Islamic Center of Southern California. (Photo by Christopher Dibble)

“Have you seen our prayer room?”

Mahmoud Harmoush bolts up a stairway on the campus of Claremont School of Theology, the tails of his navy sports coat flying. He’s a stocky man of 52, quick on his feet, with a beard flecked salt and pepper. On the first day of spring semester, just a few students have returned to the United Methodist graduate school in this Southern California college town. Harmoush, a master’s candidate, had hustled from his home in Temecula—an hour south—to an 8:30 class that morning on interfaith counseling, driven home, and then returned. He was ready to dash to an afternoon seminar on Islamic law, but was happy to take time for a tour.

Pushing open the door marked “Cornish Rogers Prayer Room,” he steps into an area that could have been sized for a toddler’s bedroom. There is no furniture, just forest-green carpeting and a window facing east. Rumpled rugs are stacked against a wall. Photocopies of various religious symbols, including a cross, a Star of David, and the star and crescent, adorn the wall. This is where Muslims can pray when on campus. Before Claremont created the space, “Muslims pray outside, on the walk,” Harmoush says cheerfully.

A Syrian-born and trained imam who’s studying at a Protestant seminary, Harmoush is a participant in a grand, and truly American, theological experiment. At its core it asks if followers of Abraham’s three faiths—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—can, or should, study religion together.

LAST YEAR, AFTER 126 YEARS of preparing students for Christian ministry, the Claremont School of Theology announced that it had forged partnerships with a Los Angeles rabbinical school and a mosque to create Claremont Lincoln University, an institution that plans to train ministers alongside rabbis, imams, and scholars of other faiths. The alliance, the schools say, will create the nation’s first Islamic seminary, awarding the country’s first graduate degrees in Muslim leadership.

The Claremont Lincoln idea seems a natural product of the intellectual fervor that bubbles in the city of Claremont. The seminary sits across the street from the Claremont Colleges, a consortium of five liberal arts colleges and two graduate institutions that echo the Oxford-Cambridge model. The schools share facilities and services, such as the library, and students often take courses at the sister institutions, yet each school has a distinct mission.

Claremont’s community—and even scholars at competing schools—say Claremont Lincoln could be a worldwide model for teaching religion and political ethics, helping societies bridge differences and end conflict. Claremont Lincoln’s new partnerships—started in 2010—link the 224 students at Claremont’s theology school with 61 students at the Academy for Jewish Religion, California, a 12-year-old school a hour’s drive west at the University of California at Los Angeles.

In its infancy is another partnership, which would link Claremont with the future Bayan Claremont College, being established by the Islamic Center of Southern California, a mosque just west of downtown Los Angeles. Administrators at Bayan hope to build a $50 million center to educate Islamic students and imams, men and women.

Claremont Lincoln partners are quick to explain that rabbinical and divinity candidates, as well as future imams, will study at their religiously and geographically separate academies, but will join together at Claremont Lincoln for required and elective interfaith courses. This spring, for example, 30 CLU graduate students enrolled in programs that included interreligious studies, conflict resolution, and Muslim leadership.

The idea is to “desegregate religious education,” says Jerry Campbell, Claremont seminary’s president. In a world where people of different faiths are expected to work together, it doesn’t make sense, he says, to educate Muslim and Christian leaders separately and expect them to figure out later how to get everyone to get along.

“What we’ve done with Claremont Lincoln is to create a new market niche,” says Campbell, leaning back in his chair in an office that overlooks the campus and the San Gabriel Mountains. “We’re a premier place for being able to learn about your neighbors.”

Claremont’s lofty goals, though, have agitated people inside and outside the faith: some scholars say they doubt there is enough need or demand to keep open a school for imams in the U.S. or that its graduates would find much work at mosques; and several United Methodists have accused Claremont’s administration of chasing an educational fad to keep alive an institution that has struggled financially and was on the verge of losing its accreditation.

At the United Methodist quadrennial governing conference in April, made up of Methodists ranging from seminary presidents to local church elders from around the world, a few members proposed rescinding Claremont’s designation as one of the church’s 13 seminaries and withholding an annual donation, roughly $525,000 this year. The petition to remove Claremont as an official UMC seminary was defeated in committee and never made it to the floor.

IN THIS SMALL EXURB, 30 miles due east of Los Angeles, the rush to convert a historically Protestant academy into an institution where Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and atheists learn together has upended traditions and rhythms. Yet Claremont has never been a school solely for United Methodists. Students ascribe to 40 different faiths. The current cohort includes a Buddhist nun, Catholics, atheists, a practitioner of Lakota tribal beliefs, and a host of Christians ranging from spirit-filled Pentecostalists to Unitarian Universalists who include Eastern themes in their worship.

Practical concerns crop up routinely: some students, eager not to offend, ask professors how they should refer to God and Jesus Christ when in class. A task force of students and faculty can’t decide how the university should rework the interior of its stained-glass chapel to accommodate all worshippers. (What should be done with the giant Christian cross during a Jewish service?) In a school known for its liberal bent, fights have erupted in class over conservative views on head scarves and homosexuals.

Doctoral candidate Hyoju Lee of the Koran Methodist Church struggles with Claremont’s interreligious ideas. (Photo by Christopher Dibble)

On the first day of spring semester, students in an interfaith counseling class take turns introducing themselves. Hyoju Lee, a doctoral candidate from Korea, blurts out: “I am struggling with the interreligious idea.” The Korean Methodist church is conservative and homogenous, she explains, her eyebrows knitting. Multifaith endeavors might work in the ivory tower, but as someone who works at a local church, she wonders “whether it is ever possible to implement this idea in the local church?”

Many students look down at their notebooks. No one answers. Another student moves the conversation to a new subject.

CLAREMONT HAS ADOPTED A NEW PHILOSOPHY, in part, because of challenges that all American theological schools face. U.S. seminaries are struggling financially. Enrollment has plummeted, alongside donations, as more churches close and the demand for new clerics withers. But students still seem to yearn to understand religious beliefs—their own and those of other cultures. As a means of survival, several theology colleges have tied themselves to other faiths.

In New York City, the prestigious Union Theological Seminary urges students to take classes at partner Jewish Theological Seminary and is planning a new program that trains Islamic women to be leaders in their communities. Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, a partnership of nine seminaries and 11 graduate schools, will offer a new master’s program this fall in interreligious studies. Students at Andover Newton Theological School in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, study on a campus shared with Hebrew College, and the school is seeking an additional partner. The movement to cross-pollinate religious study, administrators say, has energized campuses, attracted applicants, and boosted the number of graduates pursuing nonprofit work.

“Theological education is undergoing a sea change,” says Nick Carter, Andover Newton’s president. “How do you relate to people who don’t look like you, think like you, talk like you? It’s the number one issue in the country today.”

And yet some leading scholars are dubious. “Putting these programs under one roof is nice, but in my world, it’s hard to get sustained support,” says Martin Marty, professor emeritus at the University of Chicago Divinity School, who has written about American religious history. “Jews pay for Jews and Baptists pay for Baptists,” he says. “They’d be less likely to pay for faculty with Buddhists teaching on it.”

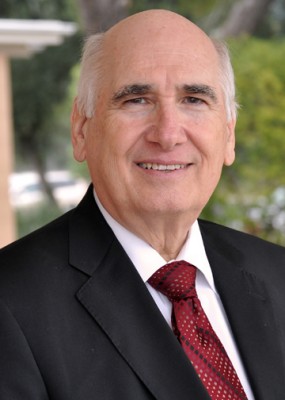

Jerry Campbell, Claremont School of Theology president, hopes to desegregate religious education. (Photo by Christopher Dibble)

JERRY CAMPBELL STEPPED INTO A MINEFIELD when he took over the Claremont School of Theology presidency in 2006. The previous president, Philip Amerson, had sparred with the academic dean over hiring and spending, cleaving faculty and leadership. The school had run consecutive deficits, totaling $5.5 million on what in 2006 was a budget of $7 million. There was no cash reserve. The market value of the school’s roughly $20 million endowment had sunk below the cost of the original gifts.

The campus—squat, concrete buildings, with exterior walkways ringing courtyards—was dingy after five decades.

Amerson, now president of Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Illinois, was belittled as a bean counter who didn’t appreciate the faculty’s intellectual wattage. He counters that he was a realist, saddled with a decrepit campus and a pampered teaching staff that was larger than the school could afford.

The week Campbell arrived, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, which reviews the instruction and finances of California graduate institutions, moved to strip Claremont of its accreditation, citing poor finances and turbulent oversight.

An ordained Methodist minister, Campbell had devoted his career to transforming universities into high-tech campuses. (Before taking the Claremont job, Campbell was chief information officer and dean of libraries at the University of Southern California.)

He also had been a volunteer commissioner with the Western Association. Campbell appealed the organization’s ruling, and made a deal with the reviewers: he’d bring in fresh blood and cut the deficit. The accreditors changed the school’s accreditation status to “show cause,” a status that gave Claremont time to address its budget and management.

With Claremont on probation, Campbell slashed spending and laid off staff. The school had depended heavily on tuition—more than $15,000 for each full-time master’s student. Somehow, Claremont had to bring in more donations or more tuition dollars. Or both.

Meanwhile, Claremont trustee and philanthropist David Lincoln told Campbell that “he didn’t think we had any institutional focus because he didn’t think we were putting our actions where our beliefs were,” Campbell says. Lincoln felt religions were paying “too much attention to theology, and not enough attention to how we get along with our fellow human beings,” Campbell says.

Claremont could no longer rely on money to train more ministers in the Wesleyan tradition. It needed more students of other disciplines.

Lincoln and his wife, Joan, offered $10 million for a new interfaith university, equal to Claremont seminary’s current yearly budget. Campbell asked for more, and the Lincolns, eager to see the project succeed, gradually raised the amount they would give to $50 million. “It just scratches the surface,” Lincoln says, compared with the endowments of Stanford or Harvard. Campbell estimates the consortium will need to raise $500 million to endow the new institution and pay for programs.

With the Christian seminary’s now lean and stable budget in place, Claremont won back its accreditation. But in 2010, the University Senate of the United Methodist Church—the elected board that accredits Methodist schools—gave Claremont a public warning. The group was concerned with Claremont’s “substantial reorientation of the institution’s mission,” which seemed to abandon the historical effort to school ministers while United Methodist money trained rabbis and imams. Campbell recast his initial proposal to show Claremont Lincoln would be a consortium hosted at the seminary, not an abandonment of it, and the senate lifted the warning.

Still, as the failed bid at this year’s general conference in Tampa to remove Claremont from the list of United Methodist seminaries and end financial support to the school demonstrated, not all are convinced. Church conservatives say Claremont—with just two dozen divinity students—has ceased to carry out a seminary’s central goal: training Christian ministers to lead congregations. Critic Mark Tooley, president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy, wrote in The American Spectator magazine: Claremont’s core dogma “is seemingly self-preservation.”

MOSQUES THROUGHOUT THE U.S. seek leaders who can weave the teachings of traditional texts with the concerns of American worshippers. It’s difficult, though, for every mosque to find trained Islamic scholars who can speak to American practitioners. To lead daily prayers, many centers settle for “someone who doesn’t speak English, but has a beautiful voice,” says Jihad Turk, director of religious affairs at the Claremont Lincoln partner, the Islamic Center of Southern California. Most imams in the U.S. were born overseas and educated abroad, learning the Koran and studying Islamic law and Arabic. Some are mentored privately in America. For years, American Muslims have discussed—at national conferences and in small groups—the need to train imams in this country. But there’s been little consensus as to what such training should include beyond classical knowlege on Islam and practical leadership skills. There’s no ordination process for imams. Past efforts to start a seminary fizzled, while federal investigations into Muslim charities after 9/11 choked off donations. A Virginia graduate school failed after the FBI raided the institution in 2003.

Turk runs a center brimming with believers born overseas. He was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona—a football-playing son of a Methodist mother and a Muslim father from Jerusalem. Turk leads prayer in Arabic, but gives sermons in English. He studied Arabic at the Islamic University at Medina in Saudi Arabia, and Farsi in Tehran.

Bayan Claremont College, Turk says, offers a two-year degree that not only teaches Arabic, Islamic law, and the hadith, or reported quotes from Muhammad, but also trains students how to counsel and solve problems, the way ministers and rabbis learn. Bayan will not align with a single branch of Islam, neither Shia nor Sunni, he says, but prepare students for different schools of law and sects.

Is there even any demand for Bayan’s American-trained imams?

“The problem is our community is so unprofessional, so scattered, individualistic, not connected, that most imams are in a very unprofessional situation,” says Ingrid Mattson, director of the Macdonald Center for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations at Hartford Seminary in Connecticut. Hartford trains about 10 people to become Muslim chaplains each year, but not one of Mattson’s students has wanted to lead a mosque. “They say imams aren’t respected, they’re not well treated, you can get fired at a moment’s notice, there are no benefits, the communities are arbitrary, the governance of the mosque can change at a moment’s notice,” she says. “ Honestly, who would want to go and work in that environment?”

THIS SCHOOL YEAR, life at the Claremont seminary campus changed. Administrators banned ham from campus social events, so as not to offend Muslims and Jews. Staff struggled to incorporate all the new religious holidays. The name of the campus cafe was changed from the “Broken Loaf” to the “Olive Branch,” its new identity hastily scrawled on the window in colored markers. It now also serves kosher food and many vegetarian dishes.

The biggest debate, though, centers on the Kresge Chapel, a modern white building with narrow, stained-glass windows. Korean students gather there for sunrise prayers. Tuesday chapel service follows the denomination of whoever preaches that day.

Inside the chapel hangs a seven-foot cross, carved and donated by Sam Maloof, the contemporary craftsman and former trustee, who died in 2009. Administrators realize that they can’t expect Muslims to feel at home with a gigantic symbol of Christianity overhead. But how does a school accommodate new members and not desecrate a religious artwork? “How do we make it movable? How do we make it look good, not cheesy by putting it on wheels?” asks Lorraine Ceniceros, a divinity student and member of the United Church of Christ denomination.

Ceniceros is part of the college president’s task force debating the thorniest issues on campus. Surprisingly, tensions pertaining to Israel have not come up, students say—but that may be because few Jewish students are willing to endure the 50-mile commute from the Academy for Jewish Religion.

What has come up is homosexuality. While the campus is known for its liberal faculty and politics, it still attracts conservative students who believe homosexuality is a sin.

Last semester, a young Los Angeles imam visiting the school, Jihad Saafir, described to a large interfaith class—one of the new course offerings by Claremont Lincoln—how he ministers to imprisoned women, many of whom are lesbians. As students pressed him with questions, the imam commented that homosexuality is a sin in Islam. One male Christian student, who is openly gay, told the imam that that was offensive. The room ignited. Some students argued with the imam, while others argued to be respectful and not fight.

Saafir talks about the incident reluctantly, parsing details. He says he tried to explain that he believes that homosexual acts, and not thoughts, are sinful. “Homosexuals don’t want to be grouped in the same category as murderers or a person who commits a crime,” he says. “They want to see it as a God-given gift, rather than a test.”

Saafir enrolled this semester at Claremont Lincoln partly because of the debate in that interfaith class. To be a faith leader, he says, “You have to overcome those kinds of obstacles. If a person claims to be homosexual, so be it. I’m not there to make enemies.”

AFTER MONTHS AT CLAREMONT, Lee, the Korean student, noticed that her Christian views were subtly changing, as if she had changed the prescription of her contacts. Jesus might not be the only way to salvation, she decided, but one way—a startling thought for an ordained evangelical minister, which she is.

“Even though I am so grateful for the changes, I’m still afraid of the uncertainty,” she says during a break from classes. “Who am I going to be if I’m influenced by all other religions?”

She doesn’t worry that the seminary’s views will sway her congregation. In America, she notes, “Sunday is a segregated day.”

Indeed that Sunday, Lee attended service at her Korean-language church in nearby Rancho Cucamonga and sang Sunday school songs to congregants’ children. The Jewish graduate students sat through rabbinical classes at the Los Angeles academy at the other end of the metropolitan area. In Temecula, Imam Harmoush taught Arabic and the Quran at his mosque’s Sunday school.

They were with God, separate and apart.