An obscure injectable medication made from pigs’ pituitary glands has surged up the list of drugs that cost Medicare the most money, taking a growing bite out of the program’s resources.

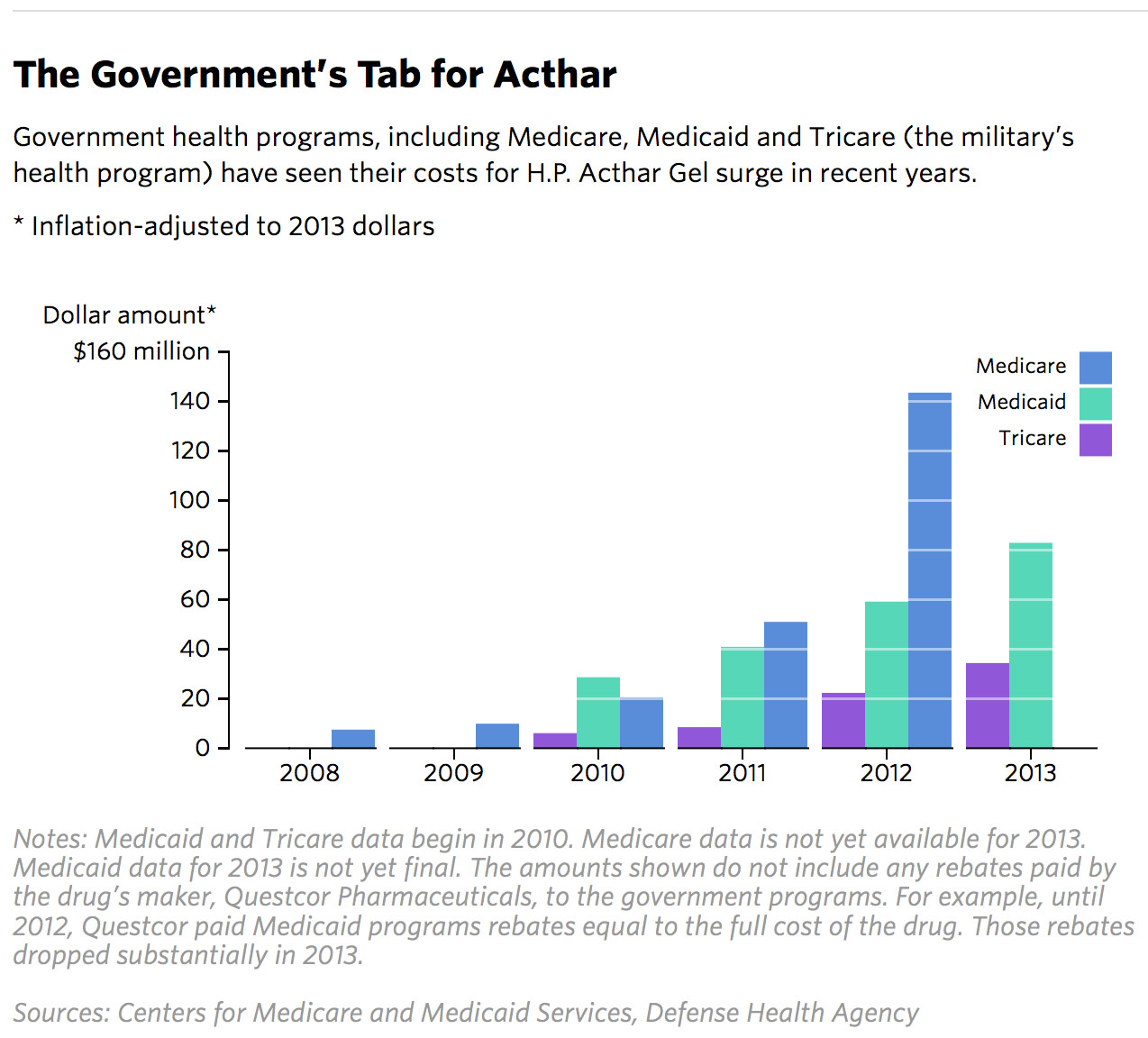

Medicare’s tab for the medication, H.P. Acthar Gel, jumped twentyfold from 2008 to 2012, reaching $141.5 million, according to Medicare prescribing data requested by ProPublica. The bill for 2013 is likely to be even higher, exceeding $220 million.

Acthar’s explosive growth illustrates how Medicare’s prescription drug program—perhaps more than private health insurers and even other public health programs—is struggling to contain the taxpayer burden of expensive therapies aimed at rare conditions.

Many outside experts say there’s insufficient evidence that the drug works better than much cheaper options for treating multiple sclerosis relapses and a rare kidney disease, conditions for which it is often prescribed. In the absence of such scientific studies, some private health insurance companies, as well as Tricare, the military’s health care program, have curtailed or eliminated spending on Acthar. Proponents of the drug say it is a worthy option for patients who have failed on other therapies.

But Medicare has imposed no limits, leaving such decisions to the private insurers paid to administer its drug program on the government’s behalf. Medicare accounted for around a quarter of Questcor Pharmaceuticals’s sales of Acthar in 2012—and that proportion is growing.

Medicare cannot bar access to medications like Acthar, even in the face of rising expense and questions about efficacy, Aaron Albright, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said in a written statement. The law mandates that Medicare’s drug program, known as Part D, cover drugs for the uses authorized by the Food and Drug Administration, he said.

Since Acthar came on the market in 1952, the rules about F.D.A. approval have changed. At the time, drug companies simply had to demonstrate that a drug was safe, rather than that it was effective. Acthar was initially authorized as a treatment for more than 50 diseases and conditions. (The list has since been cut to 19.)

Acthar isn’t prescribed often, just 3,387 times in Medicare in 2012. But Part D spent an average of $41,763 per prescription, making it one of the most expensive drugs around.

The drug ranked 139th that year, in terms of total cost, out of more than 3,000 drugs prescribed in Medicare. In 2008, it ranked around 660th.

Several of the top prescribers of Acthar have financial ties to the drug’s maker, Questcor. These doctors typically receive research grants, payments for delivering speeches on behalf of the company, or compensation for serving on advisory boards.

Acthar isn’t prescribed often, just 3,387 times in Medicare in 2012. But Part D spent an average of $41,763 per prescription, making it one of the most expensive drugs around.

But some in the medical community say the program’s soaring bill for Acthar shows Medicare needs to do more to safeguard taxpayer dollars.

Dr. Lily Jung Henson, medical director of neurology at Swedish Medical Center’s Ballard campus in Seattle, said she rarely prescribes Acthar for her multiple sclerosis patients. Medicare, she said, should at least push for more studies to determine whether Acthar works.

She said of her patients, “I certainly prescribe enough expensive drugs to them that I think are worthwhile, that I can’t afford to waste their money by giving them a drug that I can’t convince myself has been effective.”

QUESTCOR BUYS IN, INCREASING THE DRUG PRICE

Until the mid-2000s, Acthar didn’t rate as a concern for Medicare, a program for those 65 and over and for the disabled, because it was prescribed primarily for a rare infant seizure disorder and it wasn’t expensive.

That changed after Questcor bought the drug in 2001. The company has increased the drug’s price sharply since 2007, and it began marketing it for a broad menu of uses. It even funded a charity to help cover patient co-pays, taking the sting out of the drug’s out-of-pocket cost to consumers, Barron’s and The New York Times have reported.

The company has disclosed in filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission that two United States attorney’s offices and the S.E.C. are investigating its promotional practices.

Questcor declined to answer questions for this article, issuing a statement saying that it adheres to federal rules and that its promotional activities are “in line with industry best practices.” The company has suggested that investors shorting its stock may be trying to plant negative stories in the news media.

Questcor is about to be purchased by Mallinckrodt, another drug company, for about $5.7 billion in cash and stock. At a June conference, Mark Trudeau, Mallinckrodt’s president and chief executive, defended Acthar’s price to analysts, saying “it’s actually pretty, pretty inexpensive” relative to the cost of other treatments for patients who need it.

In 2008, Acthar accounted for only 202 prescriptions in Medicare, costing around $7 million. But the tally more than doubled from 2010 to 2011—and doubled again from 2011 to 2012.

Acthar is still used rarely relative to more mainstream medications, but each five-dose vial costs about $32,000. (The average Medicare prescription price is higher because some prescriptions are for more than one vial.) Although it long ago lost patent protection, the drug is a complex biologic agent, and the manufacturing process is a trade secret.

Medicare covers drugs that are even more expensive. A new drug called Sovaldi, which cures the liver disease hepatitis C, costs $84,000 for a 12-week course of treatment. Experts estimate that Medicare could spend between $2 billion and $6.5 billion on Sovaldi this year alone.

What differentiates Acthar from other specialty drugs isn’t cost, but rather its age and the dearth of studies proving its efficacy, said Ronny Gal, a senior research analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein.

“They had to prove nothing,” Gal said. “Essentially, it got grandfathered indications from a day that preceded the way we look at drugs now.”

A handful of practitioners—several of whom have ties to Questcor—have helped to drive the increase in Acthar prescriptions in Medicare.

The top 15 prescribers of Acthar accounted for 10 percent of Medicare prescriptions, an unusually high proportion, ProPublica’s analysis showed. The top four were paid by Questcor either as promotional speakers, researchers, or both.

The No. 1 prescriber, William Shaffer, a neurologist in Greeley, Colorado, gives promotional talks for the company. He wrote 78 prescriptions for Acthar in 2012, costing Medicare more than $4 million.

Shaffer, who has multiple sclerosis himself, said he was introduced to Acthar by a Questcor sales representative whose pitch he initially rejected. Then one day, the representative came in when Shaffer was seeing a multiple sclerosis patient grappling with a relapse that other drugs hadn’t helped. “What the hell, let’s try it,” Shaffer recalled saying, writing his first Acthar prescription.

When the patient came back six weeks later and said he felt better than he had in 20 years, Shaffer was a convert. “I’ve started using it more and more and I’ve had amazing results with it, without the side effects of steroids,” he said. “I had one woman ask me if Jesus made it. Another guy calls it liquid gold.”

Shaffer has used the drug himself, too, and said it worked for him.

Other specialists who treat multiple sclerosis patients are more skeptical about Acthar’s value. Dr. Claire Riley, director of the Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Care & Research Center at Columbia University, said she uses Acthar infrequently and wants evidence that it works differently for multiple sclerosis relapses than a widely used, far less expensive medication called methylprednisolone or Solu-Medrol.

“I am absolutely appalled by how expensive it is, but I do think we need to have an open mind about whether it can help people,” she said. “And if it can’t, then we really shouldn’t use it much at all.”

Kidney specialists are similarly divided on Acthar’s cost-benefit equation.

Jerry Meng, a nephrologist in Meridian, Idaho, and one of Medicare’s top prescribers of the drug, said he began using it because the standard therapy for a rare kidney condition known as idiopathic nephrotic syndrome can be harmful for those with weak immune systems.

“From a side effect profile, it’s the lesser of all evils,” said Meng, who was trained by Questcor to give promotional talks about Acthar but has not been paid to deliver any.

Meng said he hasn’t hesitated to prescribe the drug because patients receive assistance on co-pays from the drugmaker, an outside charity or some other entity. “I haven’t had a patient tell me that they’ve had to stop the medication because they couldn’t afford it,” he said.

Other kidney doctors say Acthar is essentially a “Hail Mary” pass when all else fails.

“The major problem with this treatment as I see it is the cost of the vial, and quite honestly, let’s face it, let’s be candid, this got approved at a time when the approval process was nowhere near as rigorous as it is today, ” said Patrick Nachman, a nephrologist at the University of North Carolina.

INSURERS BEGIN TO RESTRICT ACCESS

In the past few years, many commercial and public health plans have begun to take a less openhanded approach to Acthar than Medicare.

Insurers such as Aetna, Cigna and UnitedHealthcare have moved to restrict access to the drug, citing the lack of evidence that it works better than other treatments for many conditions. At a recent conference hosted by Sanford C. Bernstein, Dr. Ed Pazella, Aetna’s national medical director for pharmacy policy and strategy, explained the shift on Acthar.

Questcor’s “combination of aggressive marketing and aggressive price increases finally caused it to become a line item that a finance guy looked at and said: ‘What the hell are we paying for this? Why? What is it?’ And that’s when we started looking at what’s our policy around this stuff,” Pazella said. (A recording of Pazella’s remarks was shared with ProPublica.)

“I certainly prescribe enough expensive drugs to them that I think are worthwhile, that I can’t afford to waste their money by giving them a drug that I can’t convince myself has been effective.”

Such efforts are consistent with a broader push to control health costs that has led to a significant slowing in the rate at which those costs have risen in the last five years.

Some public programs have come to similar conclusions about Acthar.

Last year, after seeing a dramatic rise in Acthar prescriptions, the military’s health system restricted the drug’s use to infantile spasm, the condition it was mainly prescribed for before Questcor’s promotional push. Research showed that too many prescriptions had been written for patients with conditions “for which there is little supportable evidence” that Acthar is effective, the Defense Health Agency spokesman Kevin Dwyer said in an email.

Acthar usage has plummeted since the new rules went into effect. Tricare covered 725 prescriptions for the drug last year, at a cost of $34.4 million (before rebates), according to data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. Through the first five months of this year, it covered only 91 prescriptions.

Some state Medicaid programs for the poor have also limited Acthar’s use to infant seizures. Despite these restrictions, Medicaid’s spending on Acthar rose sharply last year after the government dropped rules requiring Questcor to give back almost the entire cost of the drug to states in rebates.

In his written response to questions, Albright, the Medicare spokesman, did not address whether Acthar’s rising cost had caught the attention of Medicare officials. The agency declined an interview request. The health insurers that administer Medicare’s drug program can impose restrictions, he said, but they are not required to do so. Some insurers’ rules are more restrictive than others.

Jonathan Blum, until recently the principal deputy administrator at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said in an interview that the time may have come for Congress to rethink Medicare’s limited role in assessing drugs and the legal prohibition against Medicare’s negotiation of drug prices.

“I personally think over time, the program is going to face more demands by Congress and the public to intervene, or at least use moral persuasion, to challenge or counter-pricing strategies that don’t serve the best interests of the program,” he said.

Such changes would most likely face stiff opposition. When the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services tried to change the rules governing Part D this year to allow restrictions on certain categories of drugs, backlash from the pharmaceutical industry and patient groups was so fierce that the agency was forced to back down.

Gal, the analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein, said Acthar’s story was “just an extreme case of the fundamental tensions in the system,” with cost on one side and demand on the other. “At the end of the day, there’s a limited amount of money in the system, and medicine is being rationed.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “The Obscure Drug With a Growing Medicare Tab” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.