The faculty must have money—just look at all those nice buildings on the campus. As Thorstein Veblen noted in his 1918 book, The Higher Learning in America, higher education institutions project to the “laity” an architectural impression of authority through what he calls “improved real estate.” But currently, what trickles down to adjunct instructors and other contingent faculty is not money but a myth of prestige. Mentioning that you teach at a college or university nearly invariably summons thoughts of tenured and cozy faculty who teach a handful of classes and are largely free to research, write, and travel.

Some defer to your presumed high economic position, while others—mostly parents who pay the high cost of tuition—incorrectly assume a substantial portion of the checks (or their child’s student loans) are used to compensate you, the faculty. Innocence must always have its cynical other, of course, and if you are like me, you have a wise-cracking, blue-collar cousin who distrusts the myths attached to tuition bills. You’ve likely never heard so much venom spill from the word “professor” as when he says it.

I chose an academic career and ended up like everyone else these days—overworked, underpaid, and suspended somewhere over the stagnant waters of the poem’s “moat,” albeit within the aesthetic comforts of improved real estate.

I’m partial to my cousin’s mildly insulting view. He was a third-generation ironworker who often complained that college graduates (a.k.a. my former students) did not have the practical skills needed by workers on complex construction sites. A backdraft of accusation accompanied each complaint, as if it were somehow my fault that a new hire could not read between the lines of an engineering diagram. Regardless of his false notion that faculty are lazy intellectual bums, or that English professors should teach students how weight is distributed across a bridge, and beyond its expression of outrage at perpetual tuition hikes, my cousin has a point. His view reminds us that one of the more precious ends of all education is the continual work of communication within a broad-yet-divided public sphere—and to prepare our students to do the same.

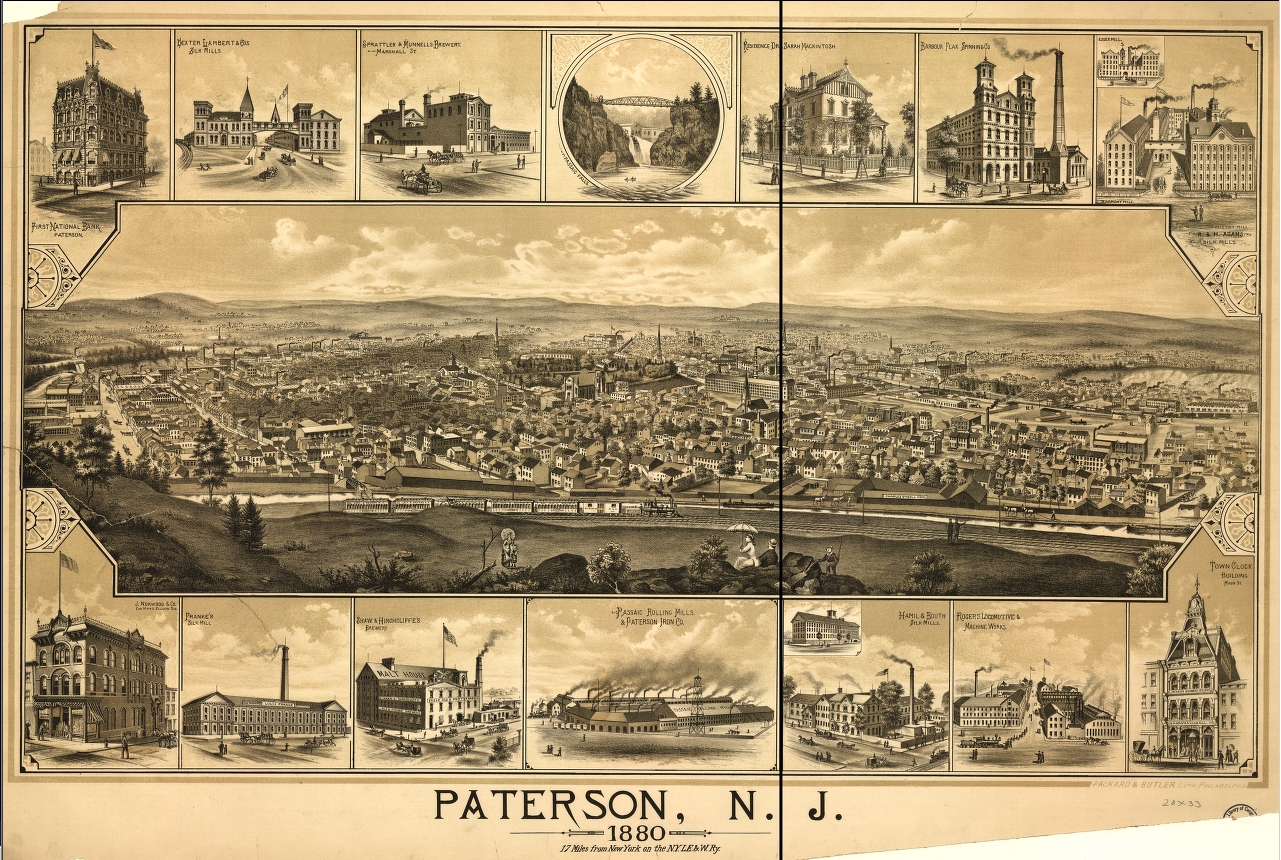

You can see the edge of Paterson, New Jersey, from certain vantages on the hill that hosts the campus that I attended as an undergraduate student and where I first worked as an adjunct nearly 20 years ago. You can see the entire lower Passaic River Valley, from where its namesake river leaves the Little Falls to the west and loops around Garrett Mountain, runs through the city, turns south, churns over the Dundee Dam, passes through Newark, then runs east through the Meadowlands to finally reach New York Harbor. The river and its falls powered the factories that made Paterson the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. Look due east along Route 3 and you can see the ridge where American poet William Carlos Williams practiced medicine, and beyond it, the Manhattan skyline.

Through book one of his poem Paterson, Williams dwells upon language and, particularly, how we communicate. Section three is of particular interest, because it has much to say about universities. In one stanza, the image of the jammed and re-directed Passaic River, funneled into countless factories to be dumped again into the stream as dye-stained waste, raises the question, “Who restricts knowledge?” The poem initially suggests the middle class is to blame, but reconsiders. Another actor, charged with instructing the middle class, appears: the university. But the obstruction lies deeper. Perhaps what is jammed and broken is not a class or classes but the channels of communication that flow from the Great Falls, the god-head of the man-city, through its peoples. Who, then, should release the flow? Who can unblock it? A final cause appears as the stanza concludes, and it is that which has always disturbed the city’s flow, since Alexander Hamilton and the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures made Paterson the nation’s first great industrial city during the late 18th century: It is the “special interests” that prevent communication and thus “make it profitable.” These special interests ensure that others should remain ignorant, or, to use one of Williams’ terms, “incommunicado.”

I knew Paterson, the city, well. Another cousin of mine worked in one of its last textile plants after coming to the United States after World War II. Looking down from her apartment window, I would watch trains carry the world from the rail yards. I briefly worked in Paterson too, for an old manufacturer of automotive batteries that a century ago advertised its goods for “horseless carriages.” That was during a brief sabbatical from the college. The immigrant family plan has always been to send children to college, and ours was no exception; I was the first in my family to go, followed by cousins and second cousins. The hope was that we might “leap the gap” that Williams portrays in his poem, the gap dividing the lower classes from the affluent. I chose an academic career and ended up like everyone else these days—overworked, underpaid, and suspended somewhere over the stagnant waters of the poem’s “moat,” albeit within the aesthetic comforts of improved real estate.

In the late 1990s, the story goes, adjunct faculty comprised roughly one third of instructors in our colleges and universities. Back then you could find part-time teaching with only a Master’s degree, and with relative ease. That’s what I did when I completed my M.A. in 1996. In fact, they came looking for me. I had a full-time day job in Manhattan and vague plans about earning a Ph.D. somewhere down the line (“everyone will retire soon,” they said). So I agreed to teach an evening class at my alma mater, and I later taught a few courses at a local community college I had also attended. This was around the time my cousin began referring to me as “professor.”

THE STATE OF ADJUNCT PROFESSORS

• Survey: 62 percent of adjuncts make less than $20,000 a year from teaching.

• The Professor Charity Case: PrecariCorps wants to draw attention to the plight of adjunct professors.

• How Colleges Misspend Your Tuition Money: You know tuition is on the rise, but you keep hearing that professors aren’t paid fairly. Where’s the money going?

• Adjunct Professors and the Myth of Prestige: Notes from 20 years of adjunct politics.

It happened that the adjuncts were organizing a collective bargaining unit when I took the gig at the four-year school. I’ll never forget the woman of color who led the drive. She spoke in an even tone, with a sure cadence in a major key. I remember thinking that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who helped organize the Paterson workers in 1913, would have been impressed. Before I knew it, I was knocking on the doors of cramped adjunct offices, distributing informational pamphlets and proselytizing for the cause. Communication was easy among colleagues and most tenured faculty supported the drive. There were good omens, too: The American Federation of Teachers council of New Jersey state locals had a mailing address in Union, New Jersey.

In the spring of 1997, the adjuncts of nine colleges and universities in New Jersey received their ballots in the mail. We voted, returned the ballots, and waited for the count. The vote was successful and we were unionized. Despite initial resistance from administrators—the special interests—it seemed an easy fight.

Nearly two decades have passed since that vote. The union I voted for still exists and it still protects its members. But other things have changed. Teachers unions are under siege across the republic as the push to further privatize education gains momentum in legislatures and courts (a push that is largely funded, of course, with public money). Adjunct labor has been further divided in many ways, with new classes of positions cropping up at various schools, our right to collective bargaining challenged or denied at every step; we are all sharing the same employment insecurity courtesy of semester-to-semester, year-to-year, or provisional multi-year contracts. There are more of us now, twice as many as then, far too many—a surplus, a logjam, a largely expendable work force of intellectual laborers. To the world outside, we are “professors.”

Most of us thought we’d be writing history after we earned Ph.D.s. And we are, though not in ways most expected. Williams’ writings, and Paterson in particular, remind me that we must adopt the long view to see and study history, so we can breathe the future into its lungs. My cousin would be horrified by the notion that poetry can teach us so much about our working lives. “But, professor…,” he would say.

In fact, Williams adopts a rather bleak view of the university in Paterson—it might come as a surprise, considering his voracious consumption of knowledge. While writing the poem, he searched far and wide for historical materials, either independently, with friends, or while assisting the Federal Writer’s Project to prepare a guidebook for the region. He often found his models in old newspapers and antiquarian lore. I don’t take it personally when he refers to university faculty as “clerks … forgetting for the most part to whom they are beholden.”

But the fact of the matter is that “clerks” is a false view, and I’m not convinced it was ever entirely true. Others may misconceive what we do, but we are teachers and we are beholden to students and, more broadly, to antiquated yet persistent (even necessary) arguments about the value of universal access to education. Stasis, Williams writes, is when there is an obstruction to the river—and to communication. But how long will the stasis persist? And what role do we play in that blockage? Is my cousin right when he argues that we should teach only practical skills, in a narrow sense? Is Williams right to note that we, the faculty, serve the special interests (in Williams’ case, likely the Paterson industrialists) at the expense of the people we should teach?

It’s difficult to answer these questions when we work with the sword of Damocles at our necks, every year a new struggle for contracts and employment. Ironically, the clerks have begun to resemble the poor in Williams’ poem. It is poetic. Though change sometimes moves slowly, the conversation about contingent faculty is now a national refrain. You can read the poem, or the engineering diagram, or the writing on the wall, and they all communicate the same thing: History, like the river, is ever on the move.