The morning of Sept. 11, 2001 remains crystal clear in most of our memories. Tragedy has a way of imprinting itself in the mind, making it easy to recall both the horrifying events and the jumble of intense feelings that followed.

A unique new research study finds a definite trajectory to the emotions we experienced that day. Fear, grief, rage: All were present, but only one — anger — rose steadily as the hours passed by.

That’s the conclusion of an analysis just published in the journal Psychological Science. By no means definitive, but undeniably fascinating, it analyzes the content of text messages sent to pagers within the U.S. during the hours after the attacks.

The pager transcripts, which were posted online by Wikileaks in November 2009, are a remarkable record of instantaneous reactions to the event as it unfolded.

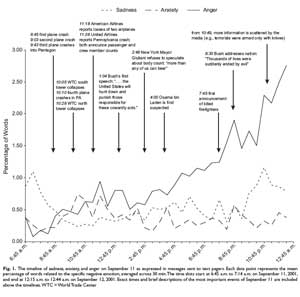

A research team led by Mitja Back at Johannes Gutenberg University in Germany separated them into five-minute blocks, and computed the percentage of words in each message related to sadness (such as “crying” or “grief”), anxiety (including “worried” or “fearful”) and anger (“hate” or “annoyed”).

“Interestingly, the attacks did not appear to immediately result in sadness, nor did single events (such as the collapse of the towers, or news of the airplane crash in Pennsylvania) influence the usage of sadness words,” the researchers report. In contrast, “anxiety was related to a number of specific Sept. 11 events,” although levels of such word usage subsided quickly after each new detail was analyzed and absorbed.

While sadness and anxiety levels — at least as measured in this way — remained relatively steady through the day, anger kept rising. “Anger was present as soon as the first airplane crashed into the World Trade Center, and it continued,” Back and his colleagues write. “The expression of anger steadily and strongly increased with ongoing information regarding the terrorist attacks.

“Both of President Bush’s speeches (at 1:04 and 8:30 p.m.), which can be interpreted as a vicarious acting out of people’s anger, led only to a temporary pause in the increase of anger. In contrast to anxiety, anger never returned to its baseline level. Instead, anger accumulated over the course of the day, and reached a level that was almost 10 times as high as at the start of Sept. 11.”

So what, if anything, does this data tell us? Some noted research psychologists offered their quick thoughts. All agreed that analyzing this data in this way was a clever idea, but they also cautioned not to read too much into it.

“We can’t be sure that people did not react primarily with sadness,” said Abraham Rutchick of California State University, Northridge. “Rather, these data suggest that people did not immediately react with explicit sadness across this particular medium.

“I want to see what happens to anger the next day, and the day after that — and also what the data looked like on Sept. 10th, so compare 9/11 patterns to those that would be observed on a normal day.”

Steven Neuberg of Arizona State University echoed both those points. “The folks who use pagers may be atypical,” he noted. Also, feeling grief may inhibit “the desire and ability to page other folks,” which would mean those emotions are underrepresented in this sample. People feeling intense sadness may be less likely to text their friends than people feeling intense anger.

That said, if these findings “reflect a real phenomenon for a substantial part of the population,” they would seem to fit certain patterns recognized by psychologists.

“As the magnitude of the event increased during the day, and as the ambiguity of what had happened began to decrease, people were able to focus more on the likely motives of the perpetrators, and the huge costs they imposed,” Neuberg said. “Anger thus grew, and its natural consequence — the desire to punish those responsible for it — increased.”

In light of these findings, it’s interesting to note a research study published in June in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. A research team led by Washington University’s Alan Lambert found that, several years after the event, “reminders of the 9/11 attacks significantly increased feelings of anger, which in turn led to systematic support for both real and fictional political hawks. In contrast, anxiety tended to have the opposite effect on such attitudes.”

So did the anger that began bubbling on 9/11 lead directly to support for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq? Neuberg doubts it; he suspects the public’s hawkish mood was more reflective of an “anxiety-based precautionary system designed to avoid a potential threat.”

But his Arizona State colleague Douglas Kenrick does see a connection. “The bilateral support for [President] Bush’s decision to start two wars in alleged response to those attacks demonstrates that such wrath [as elicited by the terrorist attack] doesn’t get replaced by a considered, rational analysis too quickly,” he said.

The new “emotional timeline” of Sept. 11, 2001 is “consistent with decades of research on conflict and aggression in the laboratory,” Kenrick added. “It also shows the folly of terrorism. The most likely reaction [to a terrorist attack] is a desire to counterattack.”