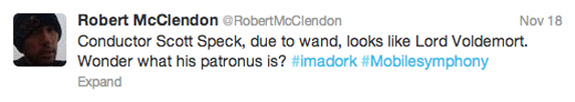

ON THE EVENING of November 18, in Mobile, Alabama, a young newspaper reporter named Robert McClendon sat through a performance by the Mobile Symphony Orchestra while quietly updating his Twitter feed.

The program that night featured Beethoven’s Eroica symphony, a passionate work that put McClendon in a reflective state of mind.

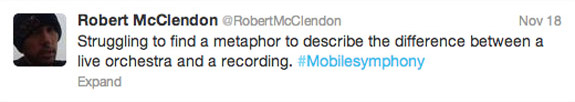

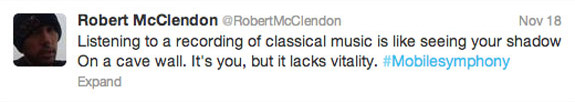

Exactly ten minutes later, at 9:58 p.m., the thought came to him:

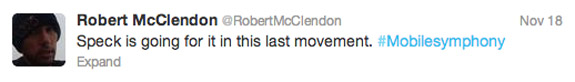

At 10:02, the orchestra plunged toward Beethoven’s finale, and McClendon leaned forward in his tweet:

And finally, at 10:06, release:

Those who prefer experiencing the classics without a running commentary are probably cringing right now. But McClendon wasn’t breaking the rules. On this particular fall evening, the Mobile Symphony was inaugurating its “tweet seats”—a row at the very back of the auditorium where patrons are welcome to text or tweet during the performance. (They are still expected to avoid unwrapping cough drops or hard candies. Some rules are inviolable.)

Although the trend has yet to hit the nation’s largest cities or most prominent companies, arts organizations from Minnesota’s Guthrie Theatre to Palm Beach Opera have begun allowing—nay, encouraging—audiences to break out their mobile devices and respond to performances in real time, even as the actors, singers, and players onstage are working hard to hold everyone’s gaze.

The rise of tweet seats is just one facet of a larger shift taking place in the performing arts—one that champions “audience engagement” and, in the minds of critics, subtly denigrates “passive spectating.” The new conventional wisdom is that it’s vital not just to put on the best show you can, but to give audiences the sort of intense, interactive, personal experience that makes them feel involved in the production. That means prepping your audience ahead of time, debriefing them afterwards, and giving them opportunities to comment or participate as well as observe. In some cases, audience engagement means inviting people to sing, play, or dance along with the performers; in others, to split their attention between the stage and (very small) screen.

Not surprisingly, many performers and older patrons of the arts hate this idea, which they regard as pandering to the young. But thankfully, the debate over participatory art needn’t devolve into a depressing bout of intergenerational warfare. The controversy raises a number of questions that are hard to answer: Is sustained focus even possible in mass audiences anymore? If not, what have we lost? But part of the discussion, taken on its own terms, boils down to a fairly tractable psychological question: Who, really, is more engaged? Is it the audience member holding a screen and responding to the action with his thumbs, or the one sitting silently in the dark with her eyes glued to the stage?

Just a few years ago, it seems, engagement referred mainly to the period of time between a marriage proposal and the ceremony. Today the term—which, in its more newfangled usages, generally connotes hands-on involvement, emotional investment, and broken fourth walls—has become a buzzword across a whole variety of domains. Educators are obsessed with measuring student engagement, which is seen as a strong predictor of academic success for today’s youth. Management gurus preach the gospel of employee engagement. And marketing professionals have written millions of words on the art of consumer engagement—the quest, in an age of declining product loyalty, to stimulate active relationships among consumers and brands.

In much the same way, engagement has become a mantra of arts administrators as they face a variety of often-chronic threats to their institutions’ survival.

The underlying dynamics are fairly simple. The core audiences of the theater, opera, and symphony—older, white, well-to-do elites—are not replacing themselves as they age out of their season tickets. To survive, arts organizations know they must reach beyond their base and appeal to new ethnic and age demographics. And in many cases, those new groups are primed for a more interactive experience, as opposed to sitting quietly through a five-hour Wagner opera. More and more Americans, for instance, hail from cultures in which art tends to be participatory (say, choral singing or social dancing) rather than something to passively observe. And of course, young people who grew up on video games and social media have their own much-remarked proclivities to remix, comment, and multitask.

For arts organizations, responding to these changes has become imperative in more ways than one. In the fall of 2011, the James Irvine Foundation—one of the top funders of the arts in California—released a much-talked-about report entitled “Getting In On the Act.” “We are in the midst of a seismic shift in cultural production,” the report proclaimed, “moving from a ‘sit-back-and-be-told’ culture to a ‘making-and-doing’ culture.” Then, as if to throw the weight of its funding power behind that shift, the foundation offered arts organizations some ideas for adapting to this new environment.

But some argue that this new conventional wisdom has gone overboard, especially in its between-the-lines disdain for passive spectating. Last fall, in response to the Irvine report, Clay Lord, who was recently named vice-president of local arts advancement for the advocacy group Americans for the Arts, published an academic paper in which he questioned “the elevation of the active audience member over the receptive one.” Watching a play is anything but passive, he wrote. And to make that case, he turned to a recent body of psychological research.

Specifically, Lord pointed to the discovery in 2006 of the brain’s system of mirror neurons. While watching someone perform a specific action—say, drinking a glass of water—we automatically activate the same neurons that would light up if we took a sip ourselves. As far as our brains are concerned, observing another person do something is very much a participatory experience. (These neurons light up particularly robustly when we’re watching something in person as opposed to on a screen. Theater company marketing departments: take note.)

Marco Iacoboni, a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA, reports that when we’re less attentive, less mirroring takes place, and mirroring is what “makes observing such a rich experience.”

So does something like tweeting reduce or increase attention?

“That’s the key issue,” says Iacoboni, who finds the question intriguing but has not studied it himself. “I know of a scientist who does live tweeting when he goes to conferences because he claims he processes the information better when he is tweeting.”

Stanford University sociologist Clifford Nass, who studies media multitasking, is skeptical. If you’re splitting your attention between watching something and tweeting your reaction, “you’re not fully engaged”; the psychological evidence is pretty clear on this, he says. His research has examined three basic elements essential for deep thinking—filtering out irrelevant information, keeping track of (and effectively sorting) relevant facts, and switching from one task to another—and has found that chronic multitaskers perform far more poorly on all of them compared to people who focus on one thing at a time.

The trouble is that modern 20-somethings seem to have little taste for full engagement.

“There is evidence beginning to suggest truly deep attention is not valued among the young,” Nass reports. “The question is, where do you get your pleasure? Do you get pleasure by being transported, which requires great immersion? Or do you get pleasure by having your focus on multiple places at once?

“That’s a cultural shift. Artists have to think about what that means, and what they want to do about it.”

THIS ISN’T THE FIRST TIME that the relationship between artist and spectator has undergone a cultural shift. No one in Elizabethan England was talking about “ye olde engagement,” but that may be because the interactive nature of theater was taken for granted. At the first productions of Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, audiences were anything but docile. This dynamic shifted in the late 19th century for several reasons, including the rise of the romantic artist-as-superhero myth. (You don’t talk back to Beethoven; you worship him.) Ironically, the pacification of the audience was largely the result of an earlier technological breakthrough.

As chronicled by Lynne Conner, chair of the Department of Theater and Dance at Colby College, the key moment occurred in 1881, when the Savoy Theatre in London—home of the still-famous Gilbert and Sullivan operettas—“became the first theater fully equipped with discretely wired electric lighting on stage and in the auditoriums.” For the first time in history, the actors on stage could be brightly lit while the audience sat in darkness. They talked or played; we minded our manners.

Some people in the arts are downright enthusiastic about putting an end to this era, and with their help, the partition between audience and artist is slowly starting to erode. A fuller embrace of technology is an important part of this transformation, says Alan Brown, the highly respected arts marketing researcher who was lead author of the Irvine Foundation report. He wonders, for instance, why arts institutions haven’t done more with video games, noting, “The Wii technology is fantastic. You could dance with Pilobolus at home, in front of the screen.” Back in the theater, technology could be a godsend for neophytes: A director could live-tweet occasional notes to a dense Shakespeare drama, to help people appreciate the poetry and follow the plot.

Lord salutes such attempts to engage with novice audience members, so long as they aren’t roadblocks to cultivating one of the highest forms of engagement: sitting quietly in rapt, still attention. “Rather than simply discarding presentational art because such art is less of an easy fit with younger and more diverse audiences, we should attempt to understand how such constituencies might be coaxed into the process, given the stories they want to see,” Lord writes, “without sacrificing all to the altar of a sing-along Sound of Music.”

There are, incidentally, plenty of ways to engage with audiences that don’t involve upstaging a performance as it’s happening. The Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, has instituted a sketching room where you can draw your own impressions of the old masters you’ve just seen. A number of orchestras, including the Pacific Symphony, in Orange County, California, conduct occasional seminars in which amateur musicians can play alongside the professionals. And many theaters now offer post-show discussions, which are becoming an art form in themselves. “How they’re being conducted is changing,” says Alli Houseworth, arts-marketing consultant. “I see the content getting a lot meatier. You have to have a really good facilitator to steer the conversation away from questions like, ‘How did you learn your lines?’”

On the more visual side of the spectrum, Washington D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company usually tries to have some element of interactivity in its lobby. During a 2011 production of A Bright New Boise, a play about belief in the rapture, patrons could spend their time during intermission working on a crowd-sourced art installation that echoed the themes of the play. You can see the results—where else?—on the company’s website. According to a follow-up survey of audience members, this opportunity to indirectly participate in the onstage debate fostered “a really strong connection” with the production, according to Deeksha Gaur, the company’s director of marketing. They were, in a word, engaged.

As it happens, Woolly Mammoth has also experimented with tweet seats, and plans to do so again despite somewhat mixed results. Jason Grote, a playwright who was not told ahead of time of their plans to allow tweeting, was not at all pleased to find audience members at a preview staring down at their phones. While conceding that some work might lend itself to real-time social media—say, “long-form performances like Robert Wilson, or Claes Oldernburg-style installations or happenings”—he’s convinced that, in most cases, “theater, dance, and performance is better without electronic distractions.”

Back in Mobile, Robert McClendon was, on balance, fairly positive about his social-media experiment. “The exercise helped transform me into more of an active listener, a true observer instead of merely an audience member,” he wrote in the Press-Register after the performance. But he had one qualm. Accompanying the symphony that night was a violin soloist named Chee-Yun, whose sinuous playing made a strong impression on the young reporter.

“Given the power of her performance,” he wrote, “I regret somewhat that I spent a few precious seconds of it sending 140-character missives into the swirling void of the Twittersphere.”