Football fans like me have undoubtedly heard about the indictment of Adrian Peterson on child abuse charges for striking his four-year-old son with a thin tree branch. Pictures revealing multiple lacerations on the child’s thigh have surfaced, and exchanges regarding another of his children show Peterson has used physical discipline more than once. The case has further ignited intense debates about the use of corporal punishment. While many of us may recoil at pictures and wonder how an adult could inflict physical harm on a child, views of corporal punishment are not uniform. They have changed over time and vary by racial group.

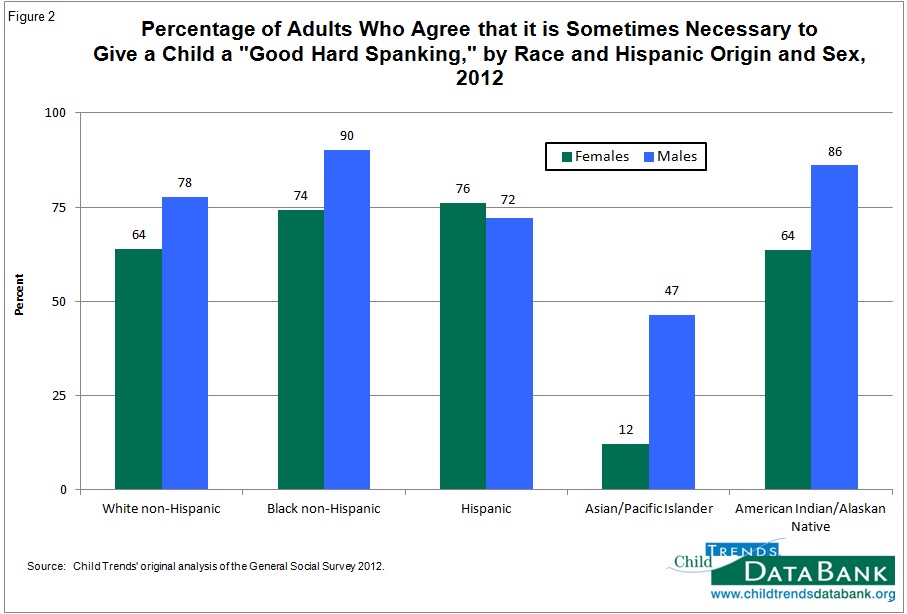

Take American attitudes about spanking over the past 50 years. In 1968, 94 percent of American adults approved of spanking a child, but by 2012, the figure dropped to 70 percent. While the majority of American parents still spank their children, some are more likely to spank than others. According a recent study of 20,000 kindergartners and their parents, black parents are the most likely to spank their children (89 percent) and Asian parents, least likely (73 percent). White and Hispanic parents fell in between, at 79 percent and 80 percent, respectively.

That Asian parents are less likely to use corporal punishment has led to speculation that there must be something unique about East Asian culture that promotes discipline without relying on physical force.

If this were the case, we would expect to see corporal punishment banned in East Asian countries, since national bans on corporal punishment reflect cultural norms and are associated with a decline in its support and reported use. Currently, 24 countries have banned corporal punishment; 19 are in Europe. There are no national bans in Asia.

That no Asian country has banned the use of corporal punishment and that it remains an accepted form of discipline reveal that differences in the use of corporal punishment cannot be attributed to culture alone.

So how do we explain the differences across racial groups? Parental education and socioeconomic status are stronger drivers of parenting strategies than differences in race or culture. Highly educated, middle-class parents are less likely to use corporal punishment to discipline their children than less-educated, working-class, and poor parents. Asian Americans are, on average, more highly educated than other Americans, including whites.

Asian immigrants are not a random sample of all Asians. Rather, they represent a highly educated subgroup, which explains why they are the least likely to use physical force to discipline their children.

This is a result of the hyper-selectivity of Asian immigration from countries like India, China, and Korea, in which immigrants from these countries are not only more highly educated than their counterparts who did not immigrate, but are also more highly educated than the general U.S. population. Hence, Asian immigrants are not a random sample of all Asians. Rather, they represent a highly educated subgroup, which explains why they are the least likely to use physical force to discipline their children.

In my research with Min Zhou, we interviewed the adult children of Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants in Los Angeles about their experiences of growing up American. As expected, those with more highly educated parents were more likely to have been disciplined with socioemotional strategies. Rather than use physical force, their parents would verbally express their disappointment or give a stern facial cue that signaled their disapproval.

Moreover, these parents praised the positive behavior of other children, both in front of their children and in front of other parents and children. By lauding positive behavior privately and publicly, these parents indirectly reinforced their expectations and provided concrete role models for their children to emulate. This dual socioemotional strategy of internal disapproval and external praise provided their children with a clear-cut portrait of model behavior, in spite of intergenerational and linguistic differences between immigrant parents and their U.S.-born children. While the second-generation Chinese and Vietnamese admitted that the constant comparisons were “irritating,” they acknowledged that their parents provided a clear signal of what behavior to follow.

Still, some of our interviewees admitted experiencing physical abuse that would rival that experienced by Adrian Peterson’s young son. In fact, some told us the abuse continued into their teenage years and stemmed from severe intergenerational conflicts that exploded over which college a child should attend or what career trajectory he or she should follow.

A third group of parents took socioemotional strategies to an extreme, telling their children that they were so disappointed that they could not face other parents. They were just that embarrassed about their child’s behavior or lack of accomplishments. So, the use of socioemotional strategies may help reinforce certain positive behaviors, but used carelessly or as a manipulation, it can leave children feeling just as powerless and despondent as any physical punishment.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Why Asian American Parents Don’t Spank Their Kids.”