It’s increasingly known that honey can act as a salve on the outside of the body, but tests performed on rats show honey’s traditional healing properties really do work from the inside, too — aiding weight loss, immune response and even memory.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that two-thirds of Americans over the age of 20 are overweight. An Antipodean academic sees the shift toward diets high in sugar and fat, but low in actual nutrition, as a key factor in these rising rates.

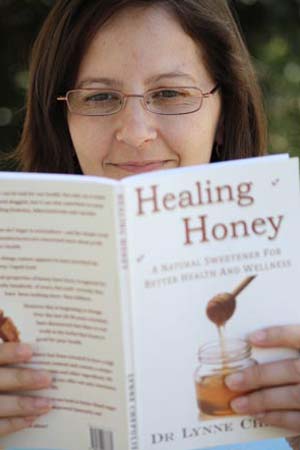

Lynne Chepulis, who recently earned a doctorate from the University of Waikato in New Zealand (home of the highly regarded, and tasty, manuka honey), has spent the last 15 years researching the potential health benefits of honey — a natural sweetener high in vitamins, minerals and antioxidants with a low glycemic index. And she’s just published a book on her findings, Healing Honey.

Foods with a high glycemic index contain carbohydrates that are easily broken down and absorbed more quickly into the blood stream than foods with a low GI. Diets containing large amounts of high GI foods are associated with increased risks of Type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hyperglycemia. Because GI carbohydrates in the American diet primarily come from sugars, refined starches and grains, high GI diets also place individuals at risk for obesity.

Chepulis believes switching the “sweetness” of diets from sugar (high GI) to honey (low GI) may improve overall health, and her extensive research of rat diets has unveiled multiple benefits of honey previously unknown to science.

Fad Diet or Miracle Drug?

On multiple occasions, Chepulis found that rats fed honey-based diets had lower body weights and 10 percent less body fat than rats fed sugar diets — an effect observed in both juvenile rats given the diets for six weeks and adult rats fed the diets for a full year. The weights of honey-fed rats were similar to but still slightly less than the weight of rats given a sugar-free diet.

(Note: In all of Chepulis’s studies, rats were fed diets proportional in size and composition to the average human New Zealander’s diet except that the sugar component was changed to honey or amylase, a sugar-free starch product with a low GI.)

Rats fed a honey-based diet also had lower overall blood sugar levels than those consuming the sugar diet.

Chepulis believes honey’s low GI value may be primarily responsible for the difference in body weight and the reduced glucose levels. In an article published in the Journal of Food Science, she explained, “Given that both amylase and honey are low GI ingredients, whereas sucrose is a high GI ingredient, these findings lend weight to the theory that glycemic index and the resultant blood sugar levels may be responsible for the reduced weight gain.”

The higher antioxidant content of honey is another explanation for the low blood sugar levels observed in honey-fed rats. Because glycation of hemoglobin — a reaction in which a sugar molecule binds to a blood cell — is driven by free radicals, an increased presence of antioxidants in a honey-based diet could also explain the lower blood sugar levels.

Chepulis also found that rats fed a honey-based diet had 15 to 20 percent higher HDL (“good”) cholesterol. More research is needed to determine what factors are responsible because neither the observed weight loss nor the low GI value of honey can fully explain this effect.

Even without an explanation, the ability of honey to increase HDL cholesterol could be an important dietary tool for people at risk for cardiovascular disease. “(In humans) the risk of death, myocardial infarction, stroke or revascularization (is) reduced by up to 90 percent with only minimal improvements in HDL cholesterol levels,” she noted.

Honey and the Immune System

In a 2007 study, Chepulis found a 12-month honey diet induces a significant boost to an adult rat’s immune system in two similar but distinct ways.

First, rats fed either a honey or sugar-based diet had greater levels of phagocytosis (when a type of white blood cell called neutrophils engulf and kill bacteria) than rats fed a sugar-free diet. However, only the rats that fed on honey had an increased percentage of lymphocytes in their white-blood-cell counts. Lymphocytes, commonly known as T-cells or B-cells, are the white blood cells responsible for identifying foreign pathogens and generating the antibodies needed to fight the harmful invaders.

While the specific mechanism behind the effect has yet to be determined, honey’s effect on rat immune systems is particularly important because neutrophil activity and lymphocyte counts have been shown to decline in aging human populations.

Psychological Effects of Honey

An experiment on honey’s impact on behavior found that honey-fed rats had better spatial memory and lower anxiety than rats fed either a sugar-based or sugar-free diet.

In a “Y Maze” test, in which rats choose to explore either a previously known or new arm of a maze, Chepulis observed a larger proportion of rats fed the honey diet entered the novel arm first — an indication of better spatial memory.

Similarly, honey-fed rats in an “Elevated Plus Maze,” where they can choose to explore raised platforms with or without walls, spent larger percentages of time on the “open” platforms. This increased interest in the less secure arms of the maze indicates decreased anxiety levels than rats fed sugar or sugar-free diets.

Because rats fed the sugar-free diet performed less well than those fed honey, a diet with low GI content cannot explain the differences in anxiety and spatial memory. Instead, Chepulis credits the antioxidant content of the honey for decreasing anxiety and improving the spatial memory of the rats in her study.

“This is in keeping with studies that honey can decrease anxiety in rats,” she wrote in her doctoral thesis. “In addition, dietary antioxidants improved cognitive performance in clinical studies, and antioxidant intake correlated with improved memory scores when ingested at levels similar to those used here.”

Humans and Honey?

Chepulis said future studies are needed to determine the optimal fructose, antioxidant and enzyme content of honey, which varies depending on region and pollen type, and how food processing affects the health benefits of the sweet substance.

While her research has only dealt with rodents, Chepulis believes her results indicate that switching human diets from sugar to honey could have numerous health and cognitive benefits — especially since the rats in her experiments were all fed diets proportional in caloric and nutritional content to those of people.

“Honey may help to improve human health if it is used as an alternative to sucrose in foods and beverages, although feeding studies in humans are required to assess its efficacy,” she concluded in her thesis.

Who knew that being healthy could taste so sweet?