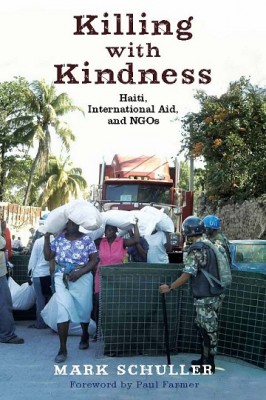

Killing with Kindness by Mark Schuller. Rutgers University Press, $26.95 (paperback).

Is humanitarian aid good for those who receive it? This deceptively simple question with a not-so-straightforward answer has been the subject of lively debate in recent years, as well as the subject of books by Timothy Schwartz, Dambisa Moyo and Linda Polman, among others.

The answer is undoubtedly yes in an acute disaster—the sort of situation which temporarily overwhelms the ability of otherwise well-functioning local governments to marshal the necessary resources to mitigate its impact.

The damage Hurricane Katrina inflicted on the city of New Orleans and rest of the Eastern Gulf Coast was simply too great to be dealt with by local agencies and authorities. Without the assistance provided by the federal government, non-governmental organizations such as the American Red Cross, and ad hoc relief efforts by private citizens and church groups, the personal suffering of those directly affected—as well as the economic impact on the region as a whole—would have been far greater.

When it comes to providing aid to populations that suffer from poor governance and chronic neglect, the issue becomes much more nuanced. Having done medical volunteer work in Haiti, I can attest to how satisfying it is to help sick children who would have otherwise have gone uncared for, or perhaps even died due to the lack of resources. However, that 85 percent of Haitian medical school graduates wind up leaving that country to work in North America certainly explains why there’s such a lack of Haitian physicians in Haiti.

This, in turn, probably has something to do with poor, sick Haitians preferring to get their care for free from well-intentioned foreigners than from Haitian physicians whose services they have to pay for. The presence of foreign medical volunteers may actually be making things worse for Haitians by undercutting their own physicians’ ability to earn a living by caring for them. After all, at some point foreign medical volunteers will stop coming to Haiti, and then what?

In Killing with Kindness, Mark Schuller, assistant professor of African American studies and anthropology at York College, CUNY, explores foreign aid to Haiti and specifically how the culture of NGOs active in that country has affected the success of their operations. He focuses on the internal culture of two NGOs, Sove Lavi (saving lives) and Fanm Tet Ansanm (women all together), as well as well their interactions with donors, and the degree to which they were able to engage their target beneficiaries in their projects and achieve results. Schuller’s analysis is based upon his own field work in Port-au-Prince between the years 2003-2005, and subsequent follow-up visits.

Schuller found Fanm Tet Ansanm to be much more successful than Sove Lavi in reaching its short-term goals and in achieving medium- and long-term success. The key to its success was its ability to engage the target beneficiaries and to consider their needs when planning its programs. Its competence was also reflected in the way it was able to promote its agenda to its foreign donors, mostly European NGOs.

Schuller contrasts this with how Sove Lavi, supported by the Global Fund and USAID, was less engaged with its beneficiaries, and often found itself forced to adhere with agendas that were many times driven by domestic American political concerns that were of little (if any) benefit or relevance to their ostensible beneficiaries.

Schuller describes how Sove Lavi, with very little room to maneuver within these constraints, co-published a pamphlet with USAID in 2006 that included recommendations to postpone sexual activity until the age of 23, in keeping with the message of abstinence as “the most appropriate policy and message for youth” to prevent infection with HIV/AIDS. This message was entirely at odds with Sove Lavi’s own campaigns of condom promotion and distribution targeting the very same demographic.

He contrasts this with how the clinic director of Fanm Tet Ansenm responded to a demand by a representative of one of the donor organizations that they set and meet specific targets for numbers of women given certain forms of contraception:

“We know you are a medical doctor, and that you are good at what you do…. We… have no objection in principle to the idea, but we know the terrain. We have been working here for almost 20 years. We know what will work here and what will not work here.” The donors wound up retreating from that demand.

Killing with Kindness concludes with a concise afterword, whose subtitles could serve as a shorthand summary of his recommendations: “For Haiti’s government: steer, not row; for USAID and other donors: accompany, not dictate.” Schuller provides a seven-point list of suggestions for how USAID (of which he is highly critical) could improve its “policy and implementation in this spirit.”

Killing with Kindness will be of interest to anyone who has ever wondered how he or she might be able to effectively help those truly in need of assistance without making matters worse for them in the long run. While meandering at times, it provides valuable insight at all levels of the process, from donor through beneficiary. It is an important book, one which deserves to be taken seriously by anyone involved in the planning and provision of humanitarian aid.

Dennis Rosen, M.D. is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. His e-book, Sleep Tight (Without the Fight) will be published by Harvard Health Publications in early 2013.