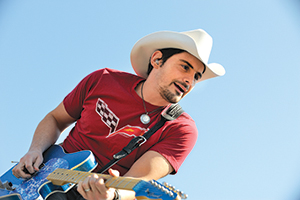

A man in a cowboy hat stands in a field, next to a tractor, guitar in hand. The hat is white and the man is white and the tractor is red. This is the music video for one of the most popular songs in America right now, a song that name-checks Billy Graham, sweet tea, NASCAR, and biscuits with gravy. For good measure, the hit single also quotes generously from “Dixie,” the unofficial Confederate anthem once performed by blackface minstrels, in which a freed slave sings longingly about the plantation of his birth.

For pop-country listeners, this song has been on heavy rotation during a particularly fraught time in North-South relations. Released in the fall, the single began its climb up the country charts in the final days of the 2012 presidential campaign. It continued its rise after the reelection of Barack Obama, as citizens in Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas filed online petitions—garnering more than 25,000 signatures apiece—to secede from the Union.

As if that didn’t produce loud enough sesquicentennial echoes of the Civil War, the blue-state national media—fresh from viewings of Lincoln and Django Unchained—spent the first weeks of 2013 fretting over the Southern Problem. In a much-discussed New Yorker article, George Packer argued that the region’s political isolation was near complete. Other prominent voices picked up on the thread. “The South has decided to be defeated and dumb,” wrote Garry Wills in The New York Review of Books in late January, “the home of lost causes and nostalgic lunacy.”

Throughout all this, the hit country single—it’s called “Southern Comfort Zone,” and it’s by Brad Paisley—kept climbing the charts. It finally peaked in February, when it became the second-most-heavily-played song on the country dial.

For those who read The New York Review and listen to top-40 country radio—a small group, in my experience—the song may have introduced a distinct note of cognitive dissonance to all the talk of terminal Southern backwardness. In it, Paisley earnestly invokes a whole slew of nostalgic Southern touchstones. But he bends them to an unexpected purpose.

“Not everybody drives a truck. Not everybody drinks sweet tea/ Not everybody owns a gun, wears a ball cap, boots, and jeans,” he sings in the opening verse. Then, in the chorus, he breaks out the song’s first reference to the Confederate anthem. “Oh Dixie Land/ I hope you understand,” he sings, “I can’t see this world unless I go/ outside my southern comfort zone.”

The song, which affirms the virtues of home and the aforementioned biscuits and gravy, is unmistakably preaching to the Southern choir. But the sermon turns out to be a paean to—of all things—cosmopolitanism. In the video, Paisley starts out standing next to the red tractor, but soon he’s running through the streets of Paris, Rome, and Dublin, eventually ending up among the Masai in Africa. The song climaxes with a giant Baptist choir singing a modified refrain from “Dixie.” But unlike the nostalgic slave in the original, when Paisley sings the words “look away,” he clearly means “look away from the South.”

“Glory, glory hallelujah/ Welcome to the future,” Paisley sings—quoting the Union anthem in a country song.

And by all indications, this was a hit with the supposedly benighted Southern core audience of country music.

No doubt sheer affection for the messenger had something to do with it. Born in West Virginia in 1972 and now living in Nashville, Paisley has been topping the contemporary country charts since the early 2000s. From 2006 to 2009, he sent 10 singles in a row to No. 1. He routinely sells out arenas across the nation, and he headlined the Daytona 500 in 2011. If you don’t regularly listen to Nashville pop and aren’t familiar with Paisley’s songs, just turn to your local country station and wait.

Paisley is the consummate mainstream country star. Yet the subtle, good-humored, broadly progressive outlook of “Southern Comfort Zone” is fairly consistent with the rest of his catalog. Paisley doesn’t write protest anthems—he is anything but the Pussy Riot of the Ozarks. He writes sentimental songs about cherished institutions, familiar experiences, randy couples, and life events that choke you up. And he may be the most deft political pop artist of our time.

To be clear, most of Paisley’s songs have no political undertones whatsoever. He’s written about drinking beer, catching fish, doomed love, the silliness of pop culture, camouflage, and inspecting his date for ticks (that’s in his song “Ticks,” and it’s more appealing than it sounds). Paisley is a master craftsman of songs that uphold traditional values. But interspersed with the down-home and hokey is a distinct, carefully modulated view of the world. In Paisley’s telling, we are not living through an age of inexorable decline warmed by memories of a brighter past. We are living in a multicultural, globally connected, technologically complex universe. And we’re having a pretty good time.

To put it mildly, this is not modern country music’s default view of the world.

By many accounts, country has been allied with declinist conservatism since about 1969, when Merle Haggard released a song called “Okie From Muskogee.” Allegedly intended as a parody, the single—which elaborated on the contrast between shaggy hippies and square, upstanding rural folk—instead became an iconic hit for Haggard. “He had nailed the feelings of millions of conservative Americans who felt forgotten by popular culture,” the historian Lester Feder wrote in The American Prospect in 2007. “The marketing potential was immediately obvious.”

Country’s ties to the political right became especially explicit in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, when Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue” promised a boot in the ass to terrorists, and his “Beer for My Horses” promised swift lynching to domestic scofflaws. Country artists were free to trumpet the reddest of political beliefs (Brooks & Dunn, Lee Ann Womack, and Travis Tritt all stumped for George W. Bush’s reelection), but they learned to fear reprisals for going too blue. When Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks told a London audience in 2003 that she was ashamed of the 43rd president, her group was boycotted, threatened, and essentially exiled from the genre of country music.

Now that the war on terror has moved off of center stage, most country singers are back to writing about the basics—relationships, family, home. It’s a conservatism of affect, mainly. Modern country music, writes the sociologist Jennifer Lena, “valorizes a return to ‘simplicity,’ moral clarity, social stability and cohesion, small-scale community and a ‘slow pace,’ honesty, loyalty, and tradition—all of which are usually framed as ‘in decline.'” Recent research has even begun to locate country’s affinity for conservatism—and vice verse—at the psychological level: it’s an “upbeat and conventional” genre for “low-openness” folk.

So how does one of country’s most popular stars release a progressive top-10 song and still remain inside the fold? Very, very carefully. In “American Saturday Night,” the up-tempo title track from Paisley’s 2009 album, he breezily paints a picture of date night in a cultural melting pot—”French kiss, Italian ice/ Margaritas in the moonlight”—before concluding that it’s all part of “just another American Saturday night.” The song is an “upbeat and conventional” trifle, but one that associates globalization and immigration with romance and superior parties. Toward the end of the song, Paisley’s notes that his “great-great-great granddaddy” arrived in this country by boat. “I bet he never ever dreamed we’d have all this,” he sings—implying that his European immigrant ancestor would look at today’s America and be impressed.

The most overtly political of Paisley’s songs so far—the only one that even obliquely references actual political events—is his 2009 single “Welcome to the Future.” In it, Paisley tells three parallel stories, linking them with a chorus that says “Welcome to the future.” The first verse describes how, as a kid, Paisley wished he could watch TV on long car trips and play video games at home; now, through technology, he can. The second verse describes how Paisley’s grandfather fought against the Japanese during World War II; and how, today, Paisley himself, a Sony recording artist, videoconferences regularly with Tokyo. And the third verse describes how a high-school classmate of Paisley’s had a cross burned on his front lawn “for asking out the homecoming queen”; this stands in contrast with the implied election of the first black president. But Paisley never says Obama or election or black. Here is how the verse about Paisley’s classmate ends:

I thought about him today

And everybody who’s seen what he’s seen

From a woman on a bus

To a man with a dream

Somehow we, the listeners, understand that “today” is Election Day. We understand that Obama stands on the shoulders of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. And while the song’s juxtapositions are on the one hand kind of ridiculous—the inconvenience of not being able to play video game paralleling the sacrifices of a slain civil rights hero—they’re also necessary. We identify with Paisley’s narrator, we are eased along with a cozy tale about how crazy things used to be, and then we are brought up short. Oh right. They weren’t crazy. They were racist.

“Welcome to the Future” was Paisley’s first single in years not to make it to No. 1 on the country charts. But it did reach No. 2. The first time I heard the song, I nearly drove off the road. It wasn’t so much the implicit message about Obama that got me; it was the chorus. In it, Paisley borrows from “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”: “Glory, glory hallelujah/ Welcome to the future.”

The Union anthem? In a country song?

Outside the context of country music, the risks that Paisley takes might seem anodyne. The big positions he stakes out—America is a nation of lovable immigrants; it’s good to travel; civil rights turned out okay—are probably ones you’ve encountered in a car commercial. But context counts for a lot. When considering Paisley’s success, it’s important to note what he doesn’t say. You don’t need to vote for Obama to appreciate his historic significance (Paisley has played at the White House, but he’s never come close to stumping for the president); and you don’t need to stop drinking sweet tea just because you go see the Eiffel Tower. In the world of Paisley’s songs, loyalty need not be so fiercely defended: life is not so full of betrayals.

Up until this point in his career, Paisley has performed a deft balancing act within his albums and within many of his songs: one part provocation to five parts comfort. This has allowed him to reach a broader audience than any self-styled “political performer” ever could. But early glimpses of Paisley’s newest efforts suggest that he may be going further out on a limb than usual. Further, perhaps, than some of his fans will care to follow.

Paisley’s new album, Wheelhouse, is slated for release tomorrow. (“Southern Comfort Zone” is its lead single.) Last week, one of the album tracks was briefly leaked to YouTube: a duet with LL Cool J called “Accidental Racist.” The country singer and rapper trade rhymes about Reconstruction, Sherman’s March, Django, and Robert E. Lee. It’s a little like “Ebony and Ivory” by way of Ken Burns. At one point Paisley’s narrator refers to the Confederate flag—as displayed on his own Lynyrd Skynyrd T-shirt—as “the elephant in the corner of the South.” In the chorus he sings, without defensiveness or apology, “I’m just a white man comin’ to you from the southland/ Tryin’ to understand what it’s like not to be.”

There are, of course, genuine problems in the South that cannot be solved with even the cleverest country song. Many of them are structural and entrenched. Yet the current Southern political situation is often viewed as a problem of mind-set, and mind-set is exactly what Paisley traffics in. When Garry Wills bemoans the fact that contemporary southerners seek to diminish the legacy of slavery in their version of history, he asks, “Where are the writers” who acknowledge this history “today in the Tea Party South?” Well, Garry Wills, he’s on your country radio dial, and the fans are listening to him.

Columnists for national magazines will probably continue to write about how the South is narrow-minded, self-defeating, and hostile to change. Many of their readers will agree. And country-music stars will probably continue to exalt the South’s traditional, family-oriented way of life as if it were under attack. Most of their fans will cheer. But Brad Paisley has shown that it’s at least possible for a country star, and his listeners, to walk the line.