Carmelita Bajacan walks expertly through the thousands of candy-colored graves that litter the vast expanse of Manila North Cemetery. She navigates the stagnant puddles of water and garbage that mark a path toward her one-bedroom shack, built directly above the grave of her 37-year-old son Irish.

It’s July, the heart of monsoon season. The stench of damp and rot winds its way through the maze of tombs lining the outer walls of Manila North Cemetery. The graveyard’s sodden ground is home to Carmelita, 57, and an estimated 6,000 slum-dwellers. This is a hidden city, with hundreds of families living inside its walls.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s “War on Drugs” has killed an estimated 20,000 people, according to international human rights organizations. And the number of unlawful and unregulated killings continues to rise, with little sign of ending.

Since assuming the presidency in June of 2016, Duterte has made eliminating drugs his top priority. In his State of the Nation Address this year, Duterte indicated his crackdown was nowhere near any point of alleviation. “It will be as relentless and chilling as on the day it began,” he said. “the war against illegal drugs is far from over.”

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

It is Manila’s slum-dwellers who are heavily targeted by the violence and bear the brunt of what human rights organizations refer to as extrajudicial killings (EJKs). Most anti-drug operations are focused specifically on poor people in a handful of slum areas and public cemeteries. These operations are carried out at night, when the only witnesses are those who wield little influence and are least able to seek justice.

“It is all corrupt. The drugs are circulated, everybody knows it,” says Carmelita as she brushes fallen leaves off her son’s grave. Irish was an informant working with the Philippine National Police, supplying to them the names of alleged drug users and dealers from Manila North Cemetery’s slum community.

Manila North Cemetery is the city’s largest and oldest cemetery. It is also notoriously known as an EJK hotspot with killings reported almost every other night. Irish was shot and killed in a police anti-drug raid at Manila North Cemetery on August 3rd, 2017.

“The PNP use assets because they have information on the people here, but if the asset knows too much about the PNP operations or if the PNP no longer need the asset, they shoot them,” Carmelita says. “The police just use poor and innocent people.”

People sleep in teetering shanties constructed from salvaged wood and corrugated metal, built on top of tombs or in mausoleums intertwined among sprawling graves and decaying garbage. There is no electricity here, nor is there ready access to clean water. Even more concerning, the community claims that unarmed slum-dwellers are being shot inside the cemetery.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

Dappled sunlight splinters its way across Carmelita’s room through a crack in the ceiling. “I got a text,” she recalls, scrolling through her phone to find it: “‘Don’t come here, there has been a shooting.’ I knew immediately it was Irish who had been killed.”

“The police come in to the cemetery and search for drugs, shooting dealers and users, they seize drugs and fill out a report for their general, then they give the drugs back to the informant to sell them back to the slum-dwellers here,” Carmelita says.

“Sometimes the police search our homes but don’t find any drugs so they arrest us [Manila North slum-dwellers]. In jail they put drugs in our pockets and set the bail at 30,000 pesos—an amount that we cannot pay when we have no source of income,” she says—a claim corroborated by a recent Amnesty International report.

The night the police searched Manila North Cemetery for Shabu, the methamphetamine most commonly targeted in police raids, they also took Irish. “They handcuffed him, hit him on the back of his head, and asked him to point out drug dealers and users,” Carmelita says. “He refused.”

Irish was shot five times, though witnesses say he was killed immediately after the first shot.

Irish’s connection with the police was complex. “Many slum-dwellers are assets to the police. Irish used to be involved in drugs but he stopped years ago and became an informant working with the police,” Carmelita says.

His cousin, who works for the PNP, got Irish involved as an informant. But eventually, Irish grew fearful that he might be killed if he was deemed expendable to police operations. He wanted out. “A week before he was killed he came to me: ‘Mother, I am confused, I don’t want to do this, I want to leave,'” Carmelita says.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

“When there is a police operation Irish wore a black suit and a skeleton mask, sometimes a stocking. This is a symbol to the police that he was working with them, and so not to shoot him in a raid. But that night, on August 3rd, he was not wearing the stocking, it was in his pocket. Maybe he chose to not wear it on purpose,” Carmelita tells me, as Irish wanted to stop being an asset.

Irish was buried with his mask, black suit, and stocking.

“It’s a Filipino belief that the items you bury someone with will never come back to cause trouble in your life again,” Carmelita says. “We bury what we do not want to haunt us.”

Manila has 36,000 people per square mile, making it one of the most densely populated cities in the world, home to approximately 24 million people, of which more than one-third are poverty-stricken slum-dwellers.

With a critical housing shortage and a population set to reach 30 million by 2030, the government is struggling to cope with the influx of informal settlers who have migrated to the city from the provincial countryside seeking work in the big city.

Many find themselves squatting in impoverished neighborhoods and slums with little or no income. Manila’s urban slums are struggling with overpopulation, pollution, underemployment, and social exclusion.

In these public cemeteries families of as many as six are living in simple one-room shanty huts, constructed from salvaged materials and built next to or on top of relatives killed in the War on Drugs. The shanties loom precariously over the graves below.

Many areas where police raids take place have a history of drug use and crime. But the people living here say that’s no longer the reality. Residents allege that when the police cannot find drugs, they simply plant them.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

“Our investigations found that police and their agents routinely kill drug suspects in cold blood and then cover up their crime by planting drugs and guns at the scene,” says Phelim Kine, the deputy director of Human Rights Watch Asia.

“It would not be at all surprising that the police are ‘recycling’ both weapons and drugs for the purpose of multiple victims,” Kine adds.

But a lack of money and legal rights means any outcry from the families of the dead often goes unheard. “We as a community want legal rights so we can pursue cases against the police for what they have done to our children. And this war on drugs is also a war on the poor,” Carmelita says, “we have no money and cannot afford investigation. There will be no justice for our sons.”

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

Duterte’s crusade has produced confusing and contradictory data on “drug war” killings, from how many people have been killed to who killed them in the first place.

Out of the 91,704 anti-drug operations that were conducted between July of 2016 and June of 2018, the PNP claim responsibility for just 4,540 suspects, all of whom authorities say died during lawful anti-drug operations. International human rights organizations say the death toll is much higher, estimating that 20,000 people have been killed in the War on Drugs since Duterte took office.

In addition to the government’s official tally, witnesses describe thousands of killings carried out by the PNP in anti-drug sting operations, or by unidentified assailants in state-sponsored vigilante killings, identified by Human Rights Watch as working in tandem with the PNP. There are additional accounts that the killings are executed by extrajudicial death squads, called “Ninja Cops,” named so for their black clothing and masked faces.

Dionardo Carlos, the ex-chief superintendent of the PNP, admits to anti-drug raids inside cemeteries. “Yes, the police conduct anti-drug operations inside the cemeteries, when reports state that such illegal activities happen in the area,” he says.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

However, the PNP’s lack of records on arrests, shootings, and drug confiscation inside cemeteries means it can act unmonitored and without any official oversight—and the body count continues to rise.

Moreover, because slum-dwellers are not included in the national census, nor is there any official record of populations living in the cemeteries of Navotas, Pasay, and Manila North, there’s no sense of urgency for investigations into killings here.

It’s this lack of accountability that’s kept Elvira Miranda up at night. On the evening of August 3rd, 2017, her son, Leover, was shot and killed inside Manila North Cemetery.

Elvira, now 68, moved to Manila North Cemetery in 1966. She’s been living with her husband and children in a makeshift shanty on top of stacked graves for more than 50 years.

Leover was killed by unidentified vigilantes outside his home; Elvira believes the killing was a case of “mistaken identity.”

“Leover was mentally handicapped; he never touched drugs,” she says. “But no one will look into this. We have no legal rights. Who will protect us anyway? We are poor.”

Leover’s grave is just a few feet from Elvira’s home, which can only be accessed by a precarious old ladder and a carefully navigated walk across the stacked tombs painted in bright powder blues and pinks. “I want him close to me, I want him to feel that he is home,” Elvira says.

Seventy-year-old Ricardo Medina sits on a plastic chair nestled in the shade of an overhanging sheet of cloth and dwarfed by the surrounding graves.

His shanty home is built into a wall of stacked graves in Pasay cemetery, also located in Manila. Ricardo works here as a caretaker.

Ricardo moved to Pasay cemetery in 1967 from the provinces. He now lives here with 21 family members, of whom 18 are living and three are dead. Among the dead: his 24-year-old son, Ericardo, who was killed in an EJK on November 16th, 2016.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

“Two days before Ericardo was murdered I came out of my house and saw four masked men standing right there,” says Ricardo, pointing to a narrow, nondescript path between the graves. “I thought maybe they were looking for someone else. But after I saw him dead on the TV with his head wrapped in packaging tape and a sign tied across his chest saying ‘pusher,’ I knew they had come looking for Ericardo that night.”

Ricardo continues: “They [the police] have a game, which officer can capture and shoot 10 alleged drug dealers in one night. Ericardo was number 11 that night.”

Due to Manila’s severe overpopulation, the city is running out of space to bury the dead. And Duterte’s War on Drugs means the funeral business is booming.

Some cemetery slum-dwellers find work as masons, gravediggers, or exhumers. As such, they often bear witness to the drug war and its massive death toll.

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

Graves are under a five-year rental here and the gravediggers have the grizzly job of digging up and burning the corpses to make room for new ones. The dirt pathways between the tombs are lined with unlabeled bags of discarded bones, unclaimed by family members.

One gravedigger in Pasay pulls the decaying body of a newborn baby out of its grave with his hands. He puts it into a plastic bag to give to the baby’s family in two days’ time. “The family can no longer afford to pay rent on the grave space,” he says as he smokes a cigarette, his fingers stained. “So, I exhume the corpse and a new baby will be buried in the space today.”

Fifteen miles away, in Navotas cemetery, a caretaker stands in front of a wall of crumbling graves, taken hostage by wild weeds and built on top of compacted garbage. He points out EJK victims. “Twenty here, 30 on the other side. There were so many EJK victims in August [of 2017]. August was the worst month.”

Parents living on top of the bodies of their children, victims of Duterte’s War on Drugs, are banded together by loss and injustice. A majority voice rings through, but this is the voice of slum-dwellers, the poorest of the poor. “Everyone in Navotas knows someone killed in an EJK,” says the caretaker. “The problem is, the only witnesses are the people living here and that is not enough. The police deny EJK killings, but just look at these bullet-ridden corpses. Is this not enough evidence?”

“The abject lesson of President Duterte’s murderous ‘drug war’ is that Philippine National Police and their agents have subjected thousands of urban slum-dwellers to a brutal campaign of extrajudicial executions,” says Kine, the deputy director of Human Rights Watch Asia. “It should come as no surprise that police operations have extended to cemeteries, which house some of the very poorest of the poor.”

(Photo: Lynzy Billing)

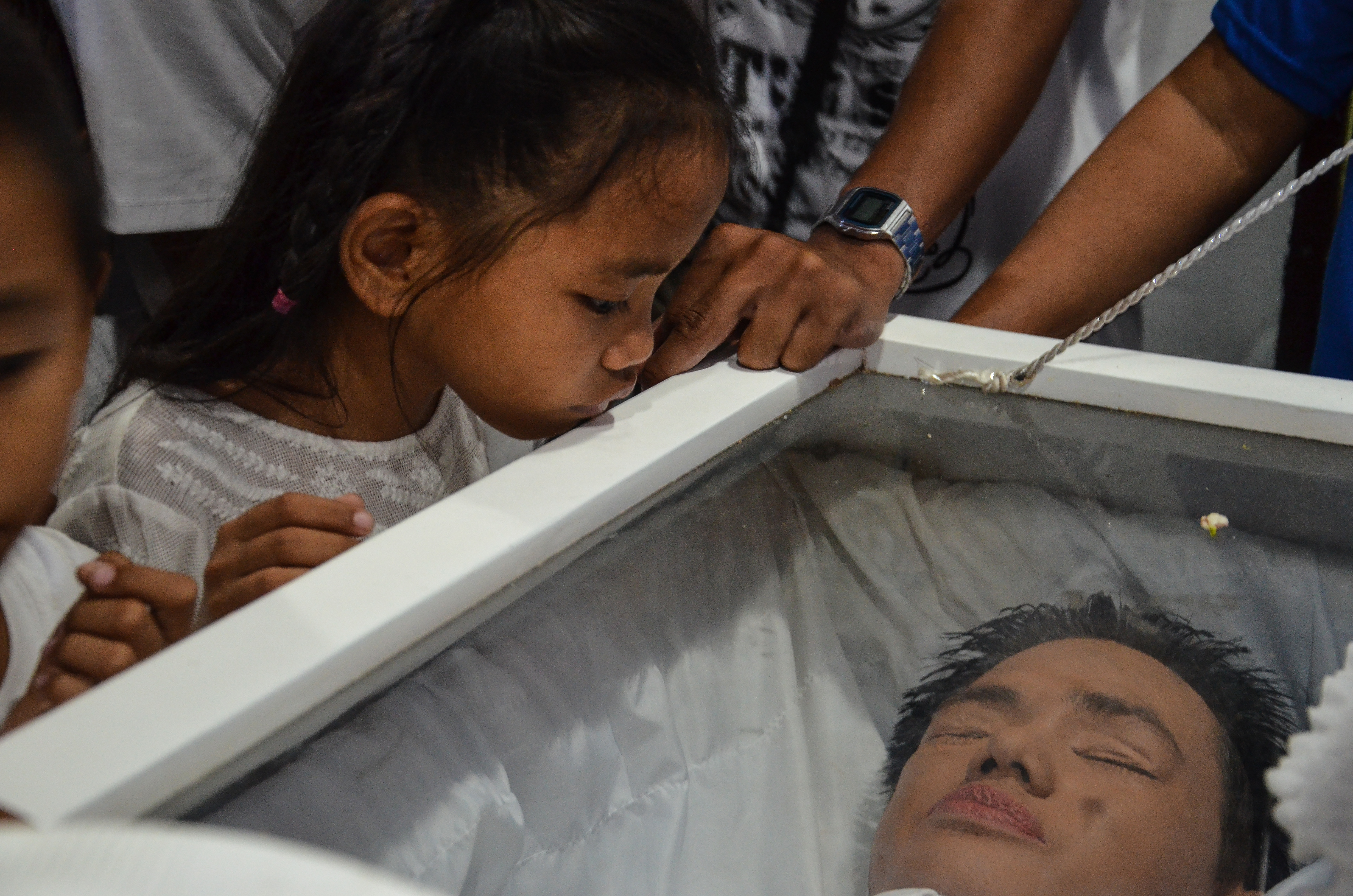

At Enrico’s wake in Navotas, his family say he was shot by unidentified vigilantes riding a motorbike. They reject allegations that he was involved in drugs and say that the killing was a case of “mistaken identity.”

“This is the sixth EJK killing recorded today,” a funeral assistant says, as Enrico’s body enters the incinerator for cremation.

Many are not as fortunate as Enrico. Their families cannot pay for a funeral; instead they join other EJK victims in mass graves.

“These bodies will be buried in the public cemetery,” the assistant says. “For them it will be like going home, where their mothers and children are. Maybe they will even be buried on the same ground they were born on.”