Ever since Nancy Torres’ son was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in November of 2017, he has been detained in California’s Orange County, not far from Torres’ home in El Monte. Though the past year and a half has been difficult, she’s tried to visit him whenever she can, and she was grateful when some local lawyers agreed to take on his case for free.

But soon, Torres fears, her son won’t be able to see her or his lawyers anymore. In March, Orange County abruptly announced that it would be ending its agreement with ICE to detain immigrants in county jails. Now, immigration lawyers fear that ICE could transfer the county’s hundreds of detainees to remote detention facilities out of the state, where they can’t see their families or attorneys.

“If he goes somewhere else, I’m scared,” Torres says. “Who’s going to visit him? Who’s going to help him?” Orange County is the latest in a growing number of cities and counties across the country that have ended their detention contracts with ICE over the past year, putting many detainees in the same position as Torres’ son. In California, five of the seven local governments that had active detention contracts have terminated their agreements since the beginning of last year.

Although not all the decisions have been politically motivated, some advocacy groups have celebrated the closures, saying they’re consistent with California’s goal to reduce immigration detention. In 2017, the state passed a sanctuary law that limited police cooperation with ICE, and another law passed that year prohibited local governments from expanding their existing detention contracts or entering into new ones. The recent push to end existing detention contracts might seem like a natural extension of those efforts.

At the same time, the decisions have had unexpected repercussions. Instead of freeing detainees when these contracts end, ICE has taken steps that sometimes make things even worse for detained immigrants. In some cases, it has responded to closures by transferring people to detention centers hundreds of miles away, where their lawyers fear they won’t have access to the same resources they have in California. In other cases, ICE has taken steps to keep the facilities open by contracting directly with private prison companies—a move that shields the detention centers from local government oversight and allows ICE to get around the 2017 law that restricts their expansion.

Because ICE has been so reluctant to release immigrants, lawyers and advocates haven’t always agreed on whether it’s a good idea to push for more cities to cut their ties to ICE. Some argue that the end of any contract is a step toward eventually reducing immigration detention. On the other hand, last year lawyers in Hudson County, New Jersey, asked the county not to end its detention contract at that time, given the legal obstacles the closure would pose for their clients. Of more than a dozen California lawyers and advocates I spoke with for this story, none said they were against the contracts ending, but some said they had mixed feelings about the decisions, while a few declined to give an opinion.

“Non-profit immigration groups were very happy to hear that California will not expand the number of beds in detention centers,” says Tess Feldman, an immigration lawyer who’s had clients affected by the contracts ending. “That doesn’t mean we ever said it was a better idea to separate these families and move people thousands of miles away.”

Last June, Sacramento County announced it would no longer hold detainees at its local jail. Activists cheered the move, which felt like a clear rebuke to the Trump administration’s efforts to expand immigration detention. In voting to end the contract, one county supervisor described it as a “moral abomination.”

The Bay Area soon followed suit: In July, the Contra Costa County sheriff announced that the local jail there would stop holding immigrants for ICE as well, ending the Bay Area’s sole active detention contract.

After both closures, lawyers and advocacy groups hoped that ICE would respond by releasing more detained immigrants on bond or parole. The federal government has discretion to use alternatives to detention, like ankle monitors, to ensure that people show up for their court dates. Lisa Knox, an attorney at Centro Legal de la Raza in Oakland, California, says she knows of at least two people who were released right after the Bay Area decision.

But in many cases, the closures didn’t result in detainees being released. After the Bay Area decision, ICE told the Mercury News that 60 detainees were sent to a private detention center in Colorado, while 20 were sent to Washington State. For Sacramento, it’s harder to find data (and ICE hasn’t responded to requests to provide it), but advocates report that some immigrants were sent as far away as Hawaii.

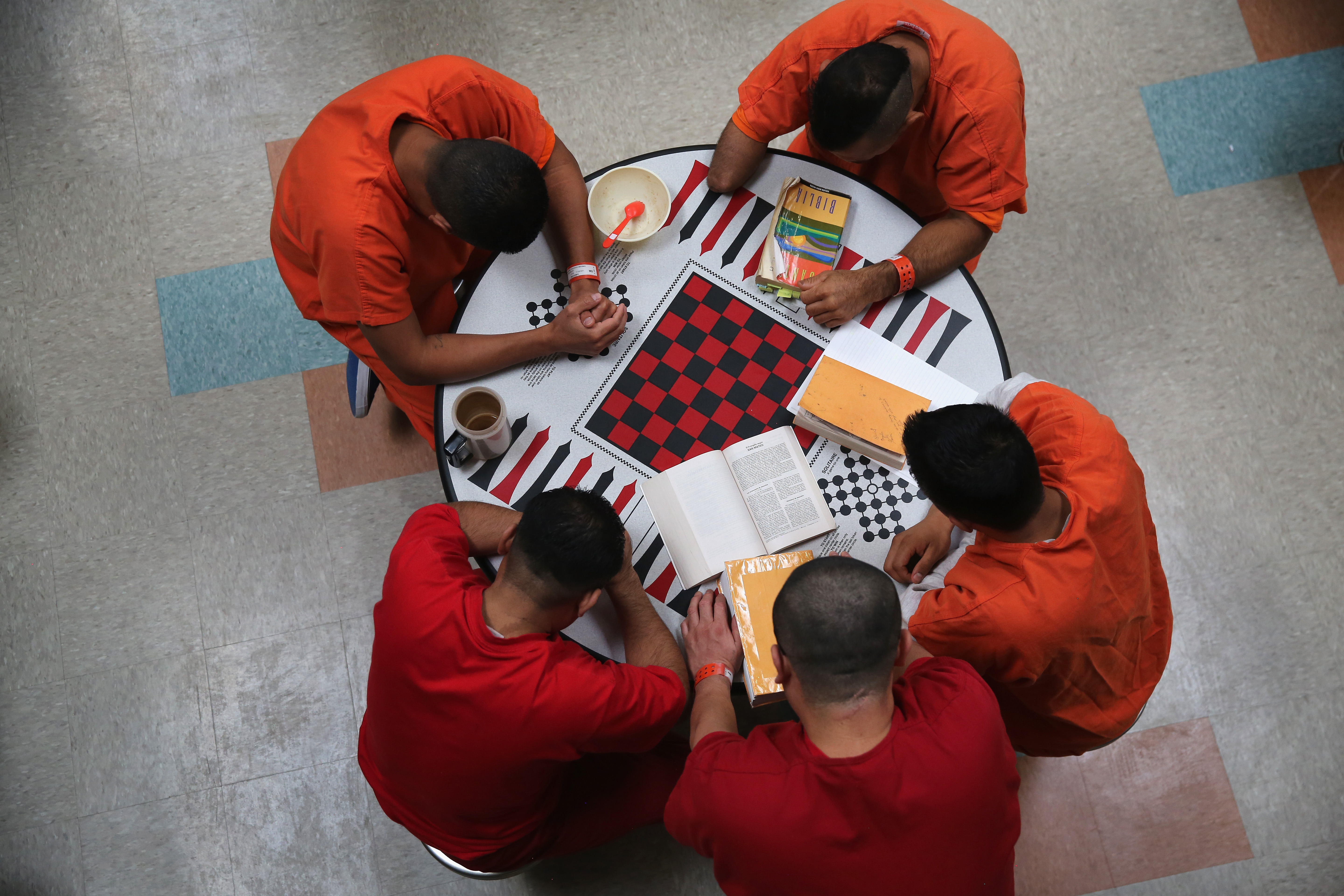

(Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

For lawyers, the transfers were particularly troubling. In the Bay Area especially, detainees had access to one of the nation’s most robust networks of pro bono immigration lawyers: In addition to local non-profits, San Francisco County and Alameda County both employ some of the only full-time public defenders in the country who represent detained immigrants. But detainees sent out of state lost access to those resources and had a much harder time finding lawyers to represent them, according to several Bay Area immigration lawyers who were working in Contra Costa County, in the East Bay, at the time.

Even in cases when immigrants retained representation, their lawyers say it became more difficult to represent their clients effectively.

“They made it essentially impossible for us to visit because we work for non-profits that can’t afford flights to Colorado,” says David Benham-Suk, a removal defense attorney at Catholic Charities of the East Bay. Meeting with clients in person is essential, lawyers say, because often they have to spend hours talking with asylum seekers about traumatic experiences from their past—and it can be hard to build that kind of trust over the phone. Some lawyers also say it became harder to communicate confidentially or exchange documents once their clients were transferred.

Additionally, transferring an immigrant out of state can create all kinds of legal complications. When ICE sent detainees from California to Colorado, it often tried to switch their cases to a different immigration court as well—a move that meant the immigrants would have to completely restart their cases under the jurisdiction of a different judge, spending more time in detention as a result. Benham-Suk and other lawyers successfully fought those legal maneuvers, but many immigrants don’t have lawyers who can do that.

In Colorado, the legal climate can also be less favorable to immigrants, since they’re no longer under the jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit and can’t benefit from certain favorable court decisions like one, for example, that makes some immigrants eligible for bond hearings after six months.

Beyond that, some immigrants felt the emotional toll of being transferred far away from their families to remote detention facilities where they rarely, if ever, had visitors. Feldman, who was an attorney at Community Legal Services in East Palo Alto at the time, says she had two clients who were sent to a private detention center in Colorado after the Bay Area detention contract ended.

The transfers “broke my clients’ spirits,” Feldman says. “By moving our clients to even more remote locations, they’re all the more dissuaded from fighting through their last legal options.”

Eventually, both her clients were ordered deported, and, worn down from being detained, decided not to appeal, according to Feldman, despite the risks they would face in their home countries.

With Orange County’s detention contract ending in August, many lawyers are now facing the same situation as Feldman, wondering how they’ll represent clients who are transferred out of state. The sheriff’s office announced the change in late March, saying the county needed to focus its resources on providing mental health care for jail inmates instead of detaining immigrants for the federal government.

In a statement after the decision was announced, ICE said the agency “will have to depend on its national system of detention bed space to place those detainees in locations farther away.”

This time, though, lawyers are ready for the transfers. In a class action lawsuit filed earlier this month, lawyers for several detained immigrants, including Nancy Torres’ son, Sergio Jonathan Moreno, argue that transferring detainees out of Southern California would violate their constitutional rights to due process, as well as ICE’s transfer policy. ICE should release as many people as possible, they say, and keep the rest in Southern California by transferring them to Adelanto, a remote private detention facility in a desert city about 90 miles from Orange County.

“We’re in a situation where the best case would be for people to be transferred to Adelanto, which is extremely difficult,” says Monica Glicken, a lawyer with the non-profit Public Law Center who’s representing Moreno. “I don’t know how we will afford it if all of a sudden all our cases are Adelanto cases.”

There’s also reason some lawyers are concerned about their clients being sent to Adelanto. Unlike Orange County, Adelanto doesn’t hold detainees in county jails. Instead, for the past eight years, the private prison company GEO Group has operated a massive detention center in the city under a three-way agreement with the local government and ICE. But in March, Adelanto’s city manager announced that the city would be pulling out of its detention contract as well—and it now looks increasingly likely that ICE will keep the detention center open by contracting directly with GEO Group. In doing so, ICE could evade California’s new law that restricts immigration detention bed space: Although the law says local governments can’t expand their detention contracts, the state can’t control contracts between ICE and a private company.

Although GEO Group hasn’t yet commented publicly on the decision, it seems clear that the company is hoping for an expansion too. Stevevonna Evans, Adelanto’s mayor pro tem, says she first learned of the plans when she accidentally walked in on a meeting in which GEO’s chief executive officer was discussing the contract with Adelanto’s city manager, Jessie Flores. According to Evans, they explained to her that ending the contract would allow the detention center to expand while shielding the city from any lawsuits against the facility.

Neither Flores nor GEO Group responded to requests for comment.

(Photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Evans worries that terminating the contract would deny the city the ability to inspect conditions in the controversial detention center. She had been hoping to establish an oversight committee, she says, but it quickly became clear that doing so will be impossible now that the contract has ended.

“It’s in the detainees’ best interest for the city to stay in the contract,” Evans says. “By getting out of this contract we’re turning our backs on 1,900 people.” Still, she ultimately couldn’t do anything to stop Flores from pulling out of the contract.

In a March 27th letter to ICE, Flores wrote that the contract would end in 90 days. After that, some advocacy groups say the detention center should close temporarily so that ICE can open up the bidding process for a new contract, in accordance with federal law. But recent precedent shows ICE may have other ideas. Earlier this year, when the city of McFarland, California, ended a similar contract with GEO Group for the Mesa Verde Detention Facility, ICE cited an exception to federal contracting law for “unusual and compelling urgency” in order to keep the facility open. The agency claimed that the detention center would need to stay open so that its nearly 400 detainees wouldn’t have to be transferred. Transfers “could result in serious injury to the detainees,” some of whom have severe medical conditions, ICE wrote.

Now, advocacy groups fear that ICE is planning to do the same thing in Adelanto. Lori Haley, an ICE spokeswoman, says the agency will keep the Adelanto facility open “as long as a viable contract is in effect.”

For some lawyers, the idea of Adelanto staying open without local oversight is particularly alarming. Last year, a scathing Department of Homeland Security report identified “serious violations” of ICE detention standards at the facility and noted that at least seven detainees had attempted suicide in recent years. (GEO Group has disputed some of the findings and said that others have been fixed.)

“It’s kind of a perfect storm, the way it’s going out in Adelanto,” says Matthew Toyama, a staff attorney at Asian Americans Advancing Justice in Los Angeles. “It’s bad news if it’s remote, it’s privately operated, and there’s no city oversight.”

It’s still hard to tell what the long-term effects of the contracts ending will be. In the short term, at least, some advocates think the Northern California decisions may have had an effect on immigration enforcement. Mario Martínez, a program coordinator at the California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice, says he has been collecting data that suggests ICE is more likely to arrest people in counties with detention centers—which could mean that ending county jail contracts with ICE would reduce arrests. Lisa Knox of Centro Legal de la Raza says that, anecdotally, her organization noticed it was getting fewer calls about ICE arrests after the Sacramento and Bay Area closures.

At the same time, if ICE does end up expanding private facilities like Adelanto and Mesa Verde in response to contracts ending, California’s overall detention space may end up increasing. At the end of April, ICE posted a request for information announcing that the government was looking for space to detain up to 5,600 immigrants near major cities in California. According to Glicken of the Public Law Center, that document looks like confirmation that ICE is hoping to expand those two private detention centers, now that it can get around the limits imposed by state law. It could also mean that ICE wants to open new private detention centers in the state—and, like Adelanto and Mesa Verde, they likely wouldn’t be subject to local government oversight.

Still, some advocacy groups argue that, despite the recent setbacks, ending detention contracts is worthwhile in the end.

“To see municipalities resisting the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant policies, not just in California but around the country, is really important,” says Liz Martinez, the director of advocacy and strategic communications at Freedom for Immigrants. “The message is clear: We don’t need detention.”

“When a community chooses to opt out of an ICE contract, the government has the opportunity to use community-based alternatives to detention,” Martinez adds, echoing a point that virtually all immigrants’ rights groups agree on. “But instead, ICE chooses to cause more suffering.”