The battle over abortion in the United States flared up this week after Senator Susan Collins met with Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. As Kavanaugh, a pro-life district judge from D.C., stands poised to replace outgoing Justice Anthony Kennedy on the court, the effort to preserve Roe v. Wade has become existential for those on both sides of the debate: Pro-choice supporters worry that Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court could put the 1973 decision that decriminalized abortion in danger of being overturned; pro-life advocates, meanwhile, are worried by Kavanaugh’s apparent reference to Roe as “settled law.”

This would not be the first time a slide to the right on the Supreme Court has thrown the future of Roe v. Wade into question; two decades ago, in 1992, a then-newly conservative court came within one vote of dismantling Roe. Understanding how the 1992 showdown played out could illuminate what might happen if Kavanaugh takes over Kennedy’s chair—and what, if anything, prevents a justice who disagrees with Roe from overturning it.

In 1992, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the most important abortion case since Roe, made it to the Supreme Court. Casey began in a district court in Pennsylvania, where attorneys representing Planned Parenthood made the case that the state’s abortion regulations—which included requirements that a woman seeking an abortion notify her husband in writing—violated the rights and liberties outlined in Roe.

Conservatives had, at that time, taken a stronghold on the court. Of all those who’d ruled in favor of Roe, only Harry Blackmun—who wrote the original majority opinion—remained. While Casey wasn’t the first abortion case since Roe, it was the first to be heard by such a solidly conservative court.

Sensing Roe‘s vulnerability, pro-life supporters pounced.

“What happened when everyone was gearing up for Casey was that pro-life groups said: ‘This is our chance to overturn Roe. This is our moment,'” says Carol Sanger, a professor of law at Columbia Law School. Conservative groups wrote a number of amicus briefs pushing for the court to “correct the mistake” made in 1973.

Four justices agreed that Roe was a mistake. In their opinion, Justices Antonin Scalia, William Rehnquist, Byron White, and Clarence Thomas argued that Roe had been incorrectly decided. Had their opinion been joined by one more member of the court, Roe might have been overturned.

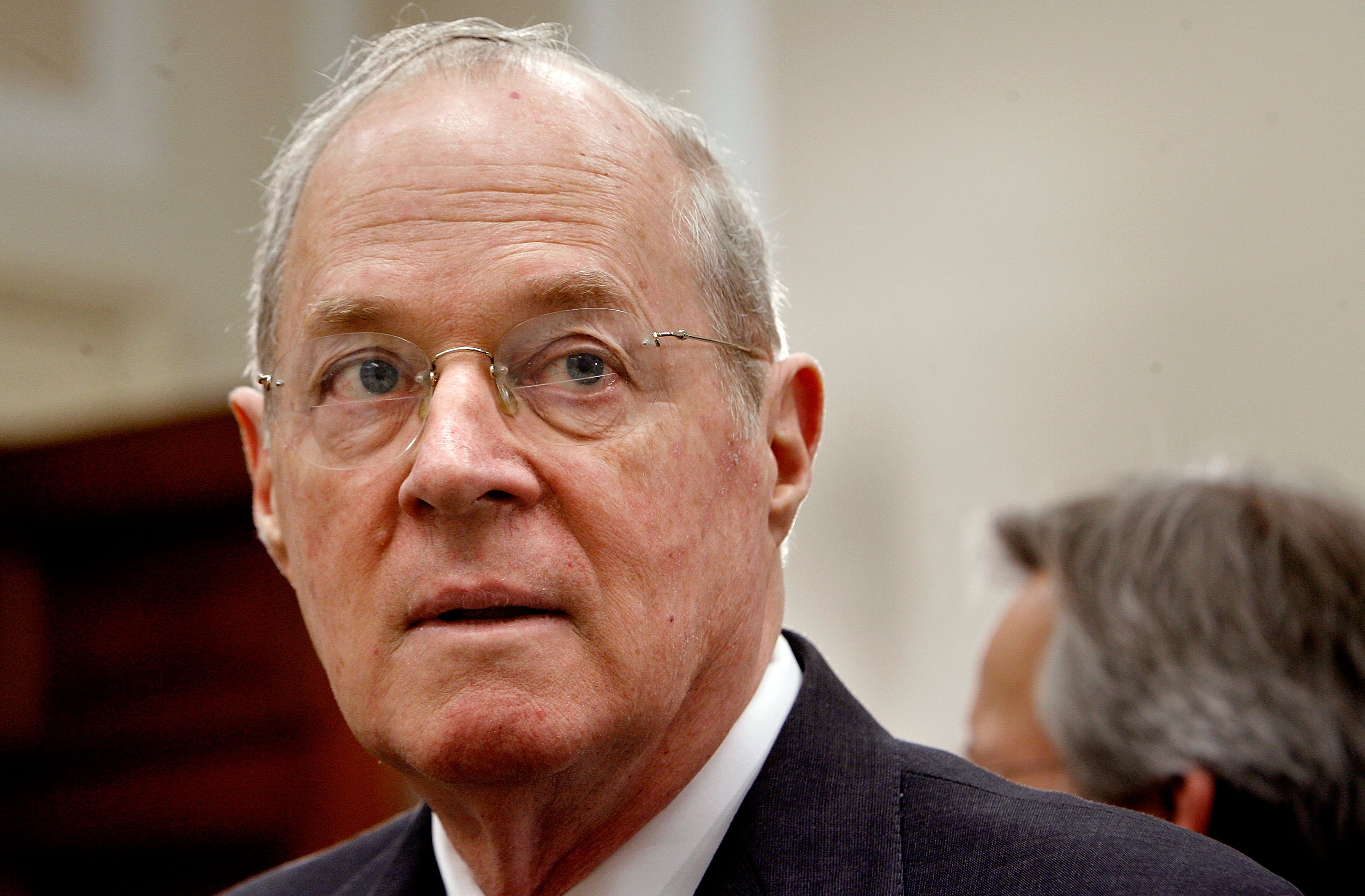

However, three conservative justices united to offer an opinion few expected. Kennedy, Sandra Day O’Connor, and David Souter (all nominated by Republican presidents) wrote a plurality opinion that refused to overturn Roe.

Sanger explains the unique O’Connor-Kennedy-Souter decision: “They said, ‘If we had been on the court in 1973, we’re not saying that we would have voted [in favor of the decision]. But we’re not on the court then. We’re on the court now, two generations later.'”

In essence, the O’Connor-Kennedy-Souter decision was not about whether or not they agreed with the original Roe v. Wade decision. It was about why, and when, the Supreme Court should overturn rulings made by previous justices. In this way, the decision not to overturn Roe came not from contemporary arguments about abortion, but rather from a commitment to the rule of law—itself a foundation of the American legal system.

“Generally with our legal system we believe … that law is more durable than people,” Sanger says. “We want to have law that people can trust and rely on in even if we have a political system that puts different people in office.”

In their opinion, O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter wrote that, because two generations of Americans had been raised in a country with legalized abortion, undoing Roe risked endangering people’s ability to rely on a steady legal system. To justify overturning the law, the justices needed to prove not just that the Roe decision was incorrect, but also that it had created an “intolerable” situation—an extraordinary scenario that warranted ruling against past precedent. The three justices ruled that Roe had not created such a situation; Blackmun and one other justice, John Paul Stevens, signed on to this specific part of their opinion, and Roe was preserved.

It’s 2018, and O’Connor and Souter are gone from the court. Kennedy—the swing vote—is leaving, and both pro-life and pro-choice activists are trying to predict what will happen when Kavanaugh takes his seat. Could the court’s newest justice unite with the other conservatives on the bench to finally “correct the mistake” made in Roe, as the decision approaches its 50th anniversary?

Answering that question means figuring out whether conservatives value precedent over ideology. In Kavanaugh’s conversation with Collins, he stated his belief that Roe is “settled law” and deserves respect under the principle of “stare decisis.” (“Stare decisis” is the latinate lawyer-speak for respecting precedent in the interest of preserving rule of law.)

While that might sound encouraging to the pro-choice camp, past justices have made similar statements and have gone on to undo precedent. It is not impossible that Kavanaugh and the court’s other conservative justices could arrive at an opinion that finds, four generations after the Roe decision, that the precedent has finally created an intolerable situation and deserves to be overturned.

(Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

However, the issue of “stare decisis” could be beside the point. According to Sanger, if the important principle in Roe is that those seeking abortion deserve access to those services, the Supreme Court could issue—and has issued—rulings that deny such access in huge swaths of the country. And they can do this all without overturning Roe.

In the 1992 Casey decision, the O’Connor-Kennedy-Souter opinion clearly established that states have a right to strongly regulate abortion. Flexing within the latitude granted by Casey, many states have found ways to narrow access to abortion by passing strict regulations on how and when abortions can be performed. Even though abortion remains legal in the U.S., access to abortion is extremely limited in many parts of the country.

No state has gone further than Texas: In 2013, the state passed a law declaring that abortion clinics must meet strict requirements to remain in operation—for example, mandating that clinics expand their hallways to make room for two gurneys—which pro-choice advocates say are effectively designed to shut down clinics. The law proved devastating for abortion providers: of the 42 abortion providers in the state, only 19 survived. That left roughly one abortion clinic per every 744,000 women in Texas.

In 2016, Texas’ regulations were challenged in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. The case was heard by an eight-person Supreme Court (President Barack Obama‘s attempt to fill the seat left by the deceased Scalia had been blocked by the Republican-controlled Senate). In the decision, Kennedy again proved a moderate and joined the court’s four liberal justices. If Casey set the expectation that states can stringently regulate abortion, Whole Woman’s Health drew the line in the sand in how far a state can go.

But in the two years since that case, the court has radically changed. Neil Gorsuch has taken Scalia’s seat, and Kavanaugh will now almost certainly replace Kennedy. In new cases, it is likely that the court will allow states remarkable latitude in limiting abortion, even as they maintain Roe. In essence, they can leave Roe in place and still limit abortion.

It seems this is what a “legal abortion” will look like in the U.S. in coming decades: access to abortion in small pockets of geographic space, and short time windows within a pregnancy. The right to abortion, and rule of law, will be preserved in name, if not in essence.