Consider this scenario: A group of wealthy nations with well-established democracies is linked in a successful economic union that has dramatically increased trade, commerce and living standards. To the south, a much poorer nation is undergoing a transition to democracy after decades of authoritarian rule, at the same time moving to open its formerly closed economy to international investment and exchange. As part of its broader transformation, the southern nation asks to join the economic union to its north.

Many residents in the north are wary. After all, the southern country has just ended decades of one-party government, and its commitment to democracy is uncertain. Decades of protectionism have left it with a bloated and inefficient bureaucracy, a motley collection of money-losing state-owned enterprises, antiquated transportation and communication networks, an underdeveloped banking and monetary system, a legal structure of questionable integrity, and a welfare state that is far less generous than the safety nets prevailing to the north. Given these deficiencies, it is hardly surprising that income in the southern nation remains a small fraction of that in the north. And given the southern country’s high fertility rates and young population, it’s also unsurprising that the nation has historically sent large numbers of migrant workers northward.

Northern policymakers have a genuine dilemma.

On the one hand, admitting the southern nation as a full-fledged member will expand the size of the union’s internal market, offer northern producers access to less expensive labor, create new opportunities for northern investors, and give residents of cold-weather climates new and sunny tourism and retirement options. Membership might also help to institutionalize democratic rule and economic reforms in the southern country.

On the other hand, granting full membership to their poor southern neighbor could, some fear, prompt a wave of factory closings and job losses, as northern firms establish new plants in the south to take advantage of lower labor costs. Other northerners fear that southern workers, suddenly free to cross borders, will migrate northward by the thousands in search of higher earnings. Some outline a doomsday scenario: Cities in the north would come to house self-contained enclaves of low-skill workers who resist assimilation into the host society.

The foregoing scenario is not hypothetical, of course. It was a concrete problem that policymakers faced during the last quarter of the 20th century in the United States — and in Europe.

Spanish President-for-life Francisco Franco died in 1975, ending four decades of fascist rule and ushering in a shift to constitutional democracy and economic reform. As part of its bid to modernize, Spain applied to enter the European Union in July 1977, which led to a prolonged negotiation that culminated in the nation’s admission on Jan. 1, 1986 (along with its neighbor Portugal).

In North America, meanwhile, a series of economic and political crises during the 1970s and 1980s led to a restructuring of Mexico’s political economy and to the emergence of competitive elections that challenged the ruling party’s monopoly. To institutionalize economic reforms and attract foreign investment, in 1989 Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari asked to join a free-trade agreement Canada and the United States had recently concluded. After several years of negotiations, on Jan. 1, 1994, Mexico joined the two countries in the North American Free Trade Agreement. Although the ruling party won the presidential election that year, voting was generally perceived to be open and fair, and in 2000, an opposition candidate won the presidency for the first time in six decades as the ruling party lost control of Congress, confirming Mexico’s transition to democracy.

Despite real similarities in their situations, the paths taken to economic union by Spain and Mexico proved to be quite different — and so did the results of those unions.

For Spain, the EU adopted full economic integration as the preferred goal, and substantial resources — equivalent to tens of billions of U.S. dollars — were made available to modernize Spanish institutions and infrastructure so they would harmonize with conditions in the north. As these investments were made, Spanish out-migration to the rest of Europe not only did not increase; it stopped, despite a continuing income gap between Spain and the rest of the EU.

In the U.S., in contrast, authorities chose not to pursue full economic integration, instead negotiating terms that were exploitive of Mexico and protective of the U.S. And since the signing of NAFTA, migration from Mexico to its northern neighbor has continued unabated as efforts to increase border enforcement have backfired, encouraging Mexican migrants in the U.S. to remain and actually increasing net undocumented migration.

Although you wouldn’t guess it from the current U.S. immigration debate or presidential campaign, many authoritative studies of EU integration and NAFTA reveal a clear lesson: If the money devoted to U.S. border enforcement were instead channeled into structural adjustment in Mexico, as was done by the EU for Spain, unauthorized migration would likely disappear as a significant demographic and political issue in North America. This assertion is not a matter of ideological belief or airy theorizing; it is based on authoritative economic measurements and real-world experience.

In 1978, after a short period of deliberation, EU member states, then known as the European Economic Community, rewarded Spain for its transition to democracy and economic liberalization, entering serious negotiations to specify how it might join the EU as a full member. In doing so, European officials built on their earlier success with Greece, a poorer nation that had already been successfully integrated. Negotiators on both sides had two central aims: They wanted to integrate Spain’s markets with those of northern Europe by specifying institutional, financial and legal changes that Spain would have to make; and they hoped to harmonize Spanish social systems with those in the north by requiring specific reforms in the administration of education, social welfare, criminal justice and employment.

European Union negotiators did not try to make Spain’s social and economic institutions identical to those in northern Europe. Rather, they sought to begin moving them toward convergence.

Before 1986, institutional change in the Spanish economy was slow and incremental, according to data from the Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices at the University of Pennsylvania. In the decade between Spain’s EU application and its final accession, the country’s “openness index” (defined as the share of gross domestic product devoted to international trade) continued to rise slowly. Following accession, however, structural economic change occurred at a rapid pace, and from 1986 to 2004, the openness index more than doubled. Over this period, the share of workers employed in agriculture fell by roughly two-thirds, the share in services increased by more than 20 percent and the share in industry held fairly steady. These structural transformations were accompanied by major dislocations. Spanish unemployment rose from just 4.4 percent at Franco’s death to peak at 24 percent in 1994 before slowly declining, finally dropping below 10 percent in 2004.

Although income rose after Spain joined the EU, the increase was not fast enough to close the gap with its northern neighbors. In fact, the absolute size of the north-south gap in income — that is, the gap in gross domestic product per capita — remained fairly constant until Spain’s application for EU entry. Thereafter, it widened slightly before resuming a pattern of economic growth that was parallel with northern Europe’s.

This income gap ought to have driven migration from Spain into northern Europe, according to a theory of migration long accepted in many political science circles, often called the neoclassical model. Under that theory, as long as a positive wage gap exists, moving costs are small and there is no legal barrier to moving, people have an incentive to migrate.

But the neoclassical theory didn’t describe modern European reality.

In 1954, an average Spaniard earned roughly $4,000 a year, in adjusted terms, while an average northern European earned some $8,000. By moving to the north, the Spaniard had a theoretical possibility of doubling his income — a real incentive for migration.

In 2004, though, the average Spaniard was making some $21,000 and the northern European roughly $26,000. There was still a wage gap, but the Spaniard couldn’t hypothetically double his income by migrating; the potential $5,000 increase in income represented a much smaller income premium of, very roughly, 25 percent, and a lesser incentive to migrate.

Under the conditions described, neoclassical theory predicts a continuing outflow of migrants from Spain toward higher-income countries, as had happened in the past. During the economic boom years from 1967 to 1973, Spain was sending out around 100,000 temporary and 100,000 permanent emigrants per year, yielding a net outflow of between 100,000 and 150,000 persons per year to destinations in Europe.

The recession of 1974 pushed the outflow to near zero, but after 1977 it rose to between 50,000 and 100,000 persons, a level that continued into the 1980s. The fear that EU membership would unleash a new wave of Spanish emigrants thus had justification both in theory and in experience.

But Spain’s entry into the EU did not increase migration into northern Europe. Instead, during negotiations leading up to Spanish accession, temporary migration began to fall; after EU entry, the number of migrants returning to Spain rose. In 1991, for the first time in history, Spain received more Spaniards than it sent out. The inflow has continued since then, the predictions of neoclassical migration theory notwithstanding.

What happened in Spain is best understood in terms of a model proposed as an alternative to neoclassical economic theory; it is commonly known as the new economics of labor migration. A comprehensive review of studies conducted by me and a panel of distinguished international colleagues has shown that total income is not the only factor driving decisions to migrate. Among other things, research by Oded Stark, an economics professor at the University of Bonn, Germany, and J. Edward Taylor, a professor of resource economics at the University of California, Davis, has shown that people migrate in response to relative incomes. The decision to migrate also appears to be driven more by a lack of access to markets for capital than by geographic differences in expected wages.

Although some people do migrate to maximize earnings, many others move abroad to finance the acquisition of a home, a business or land in the absence of viable lending markets. For example, according to a 1995 study by Laura Huntoon, a professor of planning at the University of Arizona, Spanish migrants to Germany came disproportionately from regions with high interest rates and returned to purchase houses with money they had saved in the north. The absence of well-developed social insurance and pension programs has also been shown to spur emigration.

Although Spanish entry into the EU may have failed to eliminate north-south differentials in income, it did mitigate the various market and insurance failures that had been driving migrants outward for decades. These problems were addressed with considerable assistance from the EU’s wealthier countries. In recognition that structural economic change is expensive and time-consuming, the EU made available “structural adjustment funds” to Spain to subsidize the modernization of its infrastructure.

The European Social Fund was established to invest money in education, vocational training and occupational retraining, increasing workers’ ability to adapt to industrial change and promoting greater mobility and flexibility. The European Regional Development Fund was founded to invest in regions with average incomes of less than 75 percent of the EU average, hoping to redress geographic imbalances and promote the construction and renewal of infrastructure. Finally, the European Cohesion Fund was created to invest in environmental protection, human health and transportation.

Although there have been fluctuations in response to economic cycles, the size of these transfers has steadily grown. From levels of zero before it joined the EU, transfers to Spain from the European Regional Development Fund grew to $3.5 billion in 1999. Transfers from the European Social Fund totaled around $2 billion per year in 1999, and after its inception in 1992, transfers from the Social Cohesion Fund rose to peak at around $1.7 billion in 1996 before dropping back to around $1.2 billion in 1999. EU investments in Spain from 1986 to the end of the 20th century totaled at least $51.9 billion.

These funds, and the institutional convergence and market harmonization they enabled, led to the curtailment of emigration from Spain — despite the persistence of a large north-south gap in national income and continuing high domestic unemployment. Rising access to markets for capital, credit and insurance, ongoing improvements in public infrastructure and a decline in the relative income gap transformed Spain in a few short years from a net exporter to a net importer of labor and made it an integral part of European society.

Market unification played out very differently in North America, and so did immigration patterns. Unlike their European counterparts, Canadians and Americans were unwilling to commit to full-blown political and economic integration within North America, despite their desire for greater trade and investment opportunities to the south. U.S. officials led the way in negotiating a limited integration of North American markets that paid virtually no attention to institutional and social concerns and provided no assistance whatsoever to Mexico to undertake necessary structural adjustments.

As Maxwell Cameron of the University of British Columbia and Brian Tomlin of Carleton University have shown, Mexican President Salinas and his technocratic ministers tolerated this one-sided negotiation because they very badly wanted a trade agreement, for the same reasons that Spain sought entry into the EU: to institutionalize economic reforms and to attract new foreign investment. The Mexicans were just dealing with less enlightened negotiating partners.

The first Bush administration took advantage of asymmetries of power and wealth to drive a very hard bargain, one that secured maximum U.S. access to Mexican resources and markets while conceding as little as possible to Mexico. U.S. firms gained access to Mexico’s financial, agricultural, energy, textile and manufacturing sectors, but Mexican firms were blocked in their efforts to access the U.S. transport, agricultural and textile sectors. While Mexico was forced ultimately to dismantle its system of agricultural subsidies and tariffs, the U.S. was able to keep most of its own.

Although labor and environmental concerns were subsequently addressed in weak and nebulously worded “side agreements” during the Clinton administration, little attention was paid to structural integration or institutional harmonization. U.S. trade representatives summarily rejected structural adjustment subsidies, social harmonization policies, provisions for labor mobility and immigration reform as unfit even for discussion. In contrast to the EU program of comprehensive integration, the NAFTA program was one of selective integration and unilateral action.

Mexico’s economy nonetheless behaved in a manner that was remarkably similar to what was observed in Spain. With its entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Mexico’s economy began to open, slowly at first but then at an increasing pace after the enactment of NAFTA in 1994. By 2002, Mexico’s openness index was at about the same level as Spain’s, and total trade between Mexico and the U.S. stood at around eight times its 1986 level.

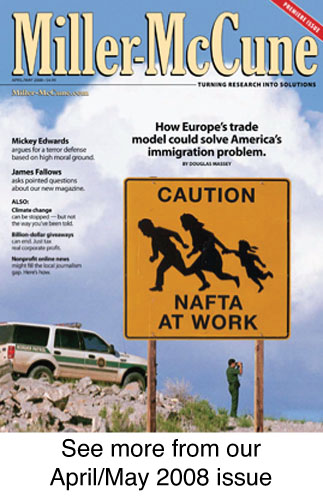

These huge increases offer unambiguous evidence of integration in North American markets — except for one. Under NAFTA, the U.S. categorically rejected the idea of integrating labor markets. To finesse the obvious contradiction in policy — geographical shifts in production and commerce, after all, strongly imply shifts in labor to service them — the U.S. embarked on a unilateral militarization of the Mexico-U.S. border. Rather than transferring resources to Mexico to assist its structural transformation, as in the EU model, under NAFTA the U.S. transferred resources to its southern border to block the inflow of migrant workers.

After Mexico’s entry into GATT, expenditures for border enforcement increased noticeably. But the rise is nothing compared with what happened after Mexico’s entry into NAFTA eight years later. The Border Patrol mushroomed from around 4,200 officers in 1994 to more than 11,000 in 2002, and the INS budget grew from $1.6 billion to $6.2 billion. Whereas the wealthier nations of the EU transferred $20 billion in structural adjustment subsidies to Spain during the first decade after market unification, the U.S. spent $32 billion to harden the border with its newest trading partner.

In the absence of any efforts toward structural integration or political harmonization, NAFTA has not been successful in reducing either the absolute or the relative gap in GDP per capita between Mexico and its neighbors to the north. On the contrary, the north-south income gap grew at an increasing pace after 1994. Whereas the north-south gap stood at $17,700 in 1986, by 2004 it had reached $24,100 — a larger income gap in both relative and absolute terms than had existed pre-NAFTA.

Given the increasing Mexico-U.S. income divide and the lack of institutional harmonization, it is unsurprising that migration between Mexico and the U.S. has not diminished. Before 1994, legal immigration to Mexico fluctuated without any consistent trend; after Mexico joined NAFTA in 1994, the trend has been unambiguously upward, albeit with sizeable oscillations.

Undocumented migration is more difficult to assess. But analyses of data from the Mexican Migration Project — a binational study directed by me and Jorge Durand of the University of Guadalajara that since 1982 has conducted yearly surveys among documented and undocumented migrants on both sides of the border — suggest that the U.S. strategy of partial economic integration with no structural assistance and massive amounts spent on border enforcement has not only failed but backfired. By concentrating enforcement resources in particular sectors along the border, U.S. policies diverted immigration flows to more remote crossing sites, where the odds of apprehension were lower but the risks of death and injury were higher, researcher Pia Orrenius at the Dallas Federal Reserve has shown.

Despite the new risks and costs, Mexicans have not stopped coming to the U.S.; they simply curtailed circular movement, lengthening stays north of the border and settling down in growing numbers. The effect of U.S. policies has thus been to increase the net rate of undocumented migration to the U.S. Rather than falling rates of emigration and declining relative income gaps — the outcomes observed following Spain’s accession to the EU — in the wake of NAFTA, North America has witnessed a widening of the north-south economic gap and an acceleration of both legal and illegal immigration.

Some might argue that Mexico’s entry into NAFTA is not comparable to Spain’s entry into the EU. After all, despite the parallels noted above, the gap in living standards between Spain and its northern neighbors was not as great as that between Mexico and the U.S. and Canada.

Even so, a natural experiment is under way, with cases that more closely approximate the Mexican example. In 2004, 10 relatively poor states from Eastern Europe entered the EU, joined by two more in 2007. The new states enter under terms similar to those enjoyed by Greece, Portugal and Spain. They are eligible for structural adjustment subsidies from the Cohesion, Regional Development and Social funds, and residents of all nations will enjoy free labor mobility by 2014.

The largest of the new EU members is Poland. Although its population is roughly the same size as Spain’s was upon its accession, after more than 40 years of communism its productive infrastructure is less advanced than was Spain’s, and its current per capita GDP is much closer to that of Mexico. Indeed, the trajectories of national income in Poland and Mexico are similar. The two countries also experienced very similar transitions to the market, at least when measured by the openness index.

Poland is the largest of the new EU entrants; it is also wealthier than most of the others. So I have also looked at development indicators in Mexico and Poland in comparison with Romania, one of the poorest of the recently admitted nations.

Despite obvious social and cultural differences, these three nations line up at roughly the same level of economic development. There is certainly little evidence to suggest that the integration of Eastern European nations into the EU poses a greater challenge than the integration of Mexico into the North American market. Yet the EU continues on the successful integrative path it blazed in Greece and Spain.

And despite the glaring failures of the NAFTA model to deliver economic growth, political stability and controlled migration, the U.S. persists in its commitment to unilateral border militarization and selective economic integration. When Mexican President Vicente Fox in 2001 proposed a revamped “NAFTA-plus” that would include a development fund to support infrastructure development and poverty alleviation, he was firmly rebuffed by Bush administration officials who, Sarah Anderson of the Institute for Policy Studies has reported, dryly noted that “we’re no longer in the business of Marshall Plans.”

The U.S. has not only refused to reconsider the failed policy of assuming that free trade will solve social and economic problems in the Americas; it has also moved to compound its earlier errors by extending the experiment to other countries in the western hemisphere. The Central American Free Trade Agreement, finalized in 2004, was negotiated along lines similar to those of NAFTA and offered U.S. interests greater access to markets in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. But it made no concessions on labor mobility. It also offered no financial assistance to countries facing wrenching structural adjustments.

The EU’s approach to regional integration offers a proven model of success for the spread of prosperity and the beneficial management of international migration. Despite initial misgivings by some EU members, the poor four — Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Greece — were successfully integrated into the system. Ireland prospered abundantly as its per capita income rose from 63 percent to 111 percent of the EU average. Although absolute income gaps persisted for the other countries, the relative size of the income differential fell everywhere.

Institutional harmonization and rising relative incomes led to the rapid reversal of long-standing trends and the remarkable transformation of all four nations into immigrant-receiving societies. There is no practical reason why the same model cannot be applied in North America and, once NAFTA is functioning effectively, to Central and South America.

The only barrier to realizing this dream is the reluctance of American leaders and the general public to define Latin Americans as “us” rather than “them,” or to see Latin and Anglo-Americans as common citizens in a cooperative American union of equal and independent states. This vision is no less achievable in the Americas than it is in Europe. Indeed, following the European model of integration offers the only realistic way out of the current quagmire of stalled economic growth, uncontrolled immigration and corrosive political bickering in North America.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.