At a sleepy outpost in the Sierra Nevada foothills in 1848, carpenter and sawmill operator James Marshall discovered several small gold flakes along the South Fork of the American River, sparking the California gold rush. Word of vast riches spread like wildfire and, seemingly overnight, San Francisco, a barren landscape of sand dunes, rolling hills, and less than a thousand residents, most of whom were Spanish speakers, was overrun by tens of thousands of people. Not all were welcome.

Most of the initial fortune seekers came from the eastern United States, but others arrived from South America, Europe, and—as word of vast riches awaiting brave miners trickled across the Pacific—Asia. The first small wave of less than a thousand Chinese prospectors was seen as simply part of the new California economy by San Francisco’s increasingly multicultural community. Whites and Hispanics generally welcomed the Chinese with some mixture of curiosity and wonder. In May of 1851, the San Francisco Daily Alta California predicted that the Chinese would soon vote, study, and worship at the same polls, schools, and altars “as our own countrymen.” Shortly after, however, the initial bonanza had evaporated and competition for mines and gold was fierce. When, four years after the gold rush began, more than 20,000 Chinese immigrants arrived at the San Francisco customs house, their reception by white miners and city officials was much cooler.

The Chinese became the single largest immigrant group to flood California during the gold rush, and it didn’t take long for frustrated white, American-born miners to blame them for depressed wages. While miners of all ethnicities struggled and toiled in the mountains and valleys of California, Chinese miners resourcefully integrated technology like the water wheel, formed cooperative groups to more efficiently mine, and earned a reputation for hard work. Most galling to American-born miners, however, was Chinese miners’ tendency to send their profits home to the families they left behind; they lamented that the Chinese were carrying off the wealth of their nation to a foreign land. Politicians passed taxes and legislation targeting Chinese involvement in the gold industry as part of a growing anti-Chinese sentiment. The Chinese had little recourse to defend themselves; as persons of color, they had no path to citizenship and could not even testify, for or against, a white person in court.

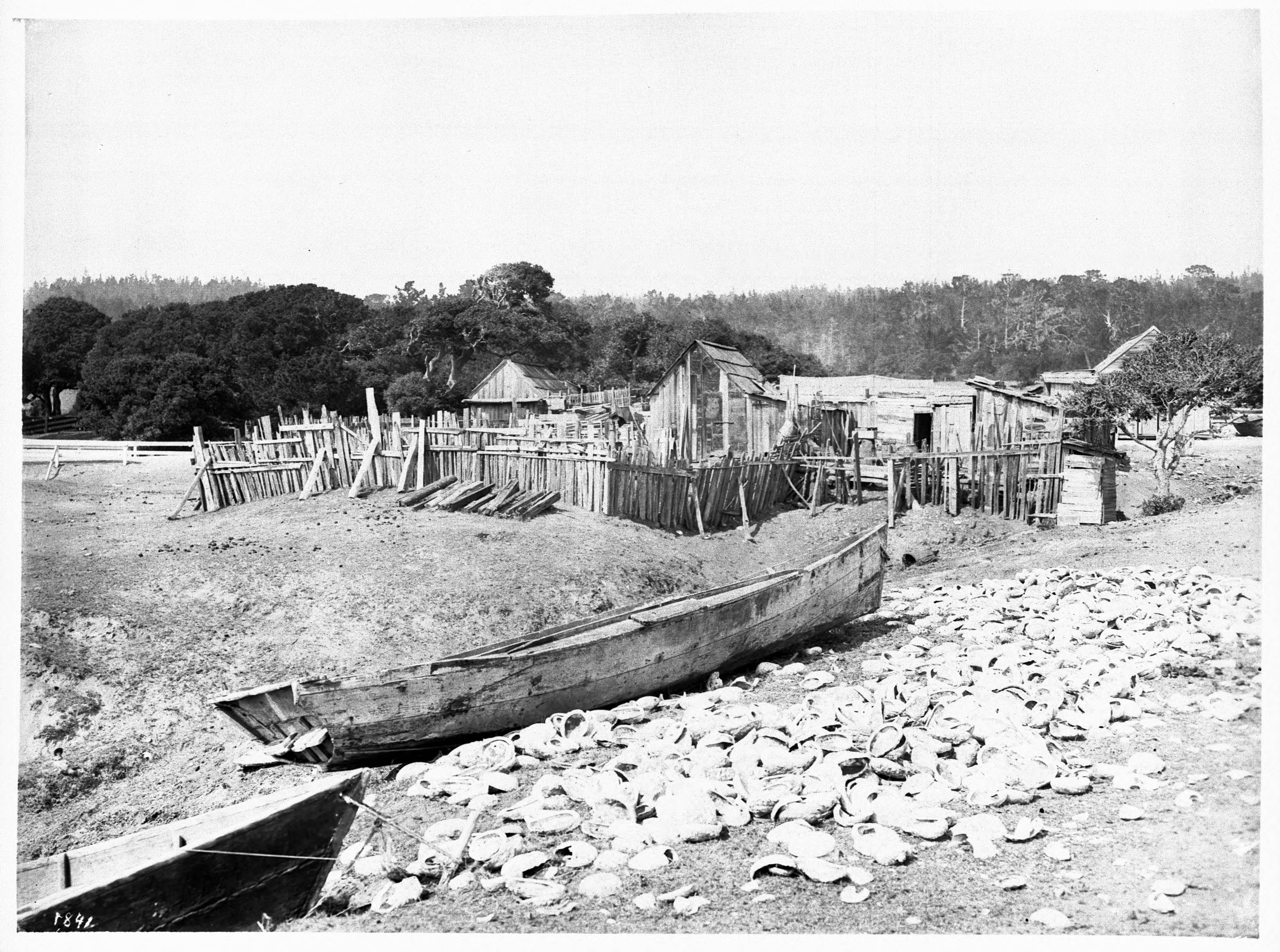

(Photo: Alfred Hart/Library of Congress)

Many Chinese immigrants turned to alternative economic opportunities such as laundries, farming, railway labor, and fishing. As a result of this shift, Chinese immigrants were the first to recognize the untapped economic opportunity of abalone. They founded the first commercial shellfishery in California, forever changing the culinary habits of the West Coast.

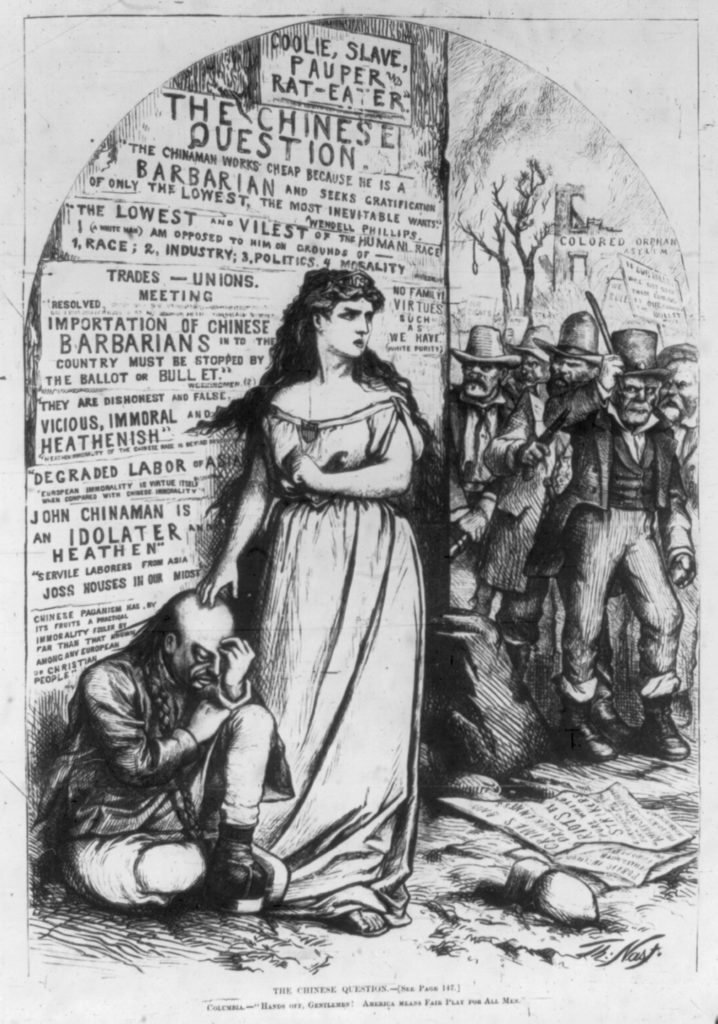

But their success in this industry was not to last. On May 6th, 1882, President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entry into the U.S. It was the first and only immigration act to designate an ethnic or racial group for exclusion from the country. Thus began six decades of institutionalized racism specifically targeting the Chinese until Congress repealed the act in 1943. The Chinese abalone fishery was among its victims. But, rather than calming anti-Chinese sentiment and pacifying Euro-American laborers, the Chinese Exclusion Act emboldened anti-Chinese proponents. Once the borders were secured, their goal was to rid America of Chinese interlopers—a period that became known as “the Driving Out.” Many Euro-Americans terrorized Chinese communities. They held anti-Chinese rallies, committed murder, and violently evicted Chinese immigrants from their jobs, homes, and communities.

American history is replete with stories of discrimination toward newcomers. When times are tough, finding an enemy is easy—and it’s usually a person who looks, acts, or speaks differently from what is “normal.” This reactionary thinking ignores the contributions of generations of immigrants who have made America great, again and again. History offers all the lessons we need to calm fears of a modern “enemy” and have faith that welcoming cultural diversity will result in a better, stronger tomorrow.

By the early 1850s, China was gripped by the Taiping Rebellion (a bloody civil war) and ravaged by famine and social unrest. Guangdong province, located in southern China along the South China Sea, was especially hard hit. So Guangdong became the launch point for thousands of Chinese immigrants, who defied governmental law and risked beheading if caught emigrating, to follow their dream of wealth and opportunity in America. They saw “Gold Mountain” as a panacea—even one small handful of gold could forever transform their lives.

But for those who made it to California, their reality held less promise than they expected. Working-class white Americans complained that Chinese laborers happily accepted longer hours for less pay, purchased goods in exclusively Chinese businesses, and segregated themselves from “American” society. Legislation and taxes were constructed to curb Chinese involvement in the gold industry. By 1853, a foreign miners tax required all miners who were not born in the U.S. to pay a licensing fee of $4 per month; in reality, it became a tax on Chinese immigrants. Racist rhetoric became quite fierce: California Governor Leland Stanford, for example, stated in his inaugural address of 1862 that “the settlement among us of an inferior race [the Chinese] is to be discouraged.”

(Photo: Harper’s Weekly/Library of Congress)

By the 1870s, anti-Chinese groups were forming throughout California. In 1877, Denis Kearney, an Irish immigrant, founded the Workingmen’s Party of California to fight corporate monopolies, government corruption, and the Chinese. With Kearney on the front lines, the organization’s cause went national, and Kearney took to ending his speeches with “The Chinese must go!” The California legislature heard activists’ cries, and the state’s new constitution, ratified in 1879, made it a criminal offense to hire Chinese employees on public works. It became virtually impossible for Chinese immigrants to find work in California outside of self-employment. Thus many retreated to the state’s social, economic, and geographic margins.

It is no surprise, then, that, at the time, Chinese food had not gone mainstream in California (or anywhere else in the U.S.), although Chinese restaurants had popped up in many cities. The cuisine of Euro- and Mexican-American California centered on cattle and the agrarian system the Spanish brought to the region in the mid-to-late 18th century. The commercial potential of marine foods was largely left untapped. Seafood had been abundantly harvested by Indigenous peoples prior to European arrival but had gone underexploited after the establishment of the Spanish Mission system.

Freed from predation pressure, abalone had become plentiful in California’s coastal waters. Native Americans had been decimated by infectious diseases and the economies of coastal (and other) tribes had been severely disrupted. Sea otters, which devour abalone, were on the brink of extinction thanks to the global fur trade, as otter pelts fetched exorbitant prices in high fashion circles. Most Euro-Americans viewed abalone as an inedible oddity. But in China, abalone were an overfished delicacy. Chinese immigrants recognized a golden opportunity to tap an unexploited market, and they had the skills to make it happen.

As an archaeologist, I have spent a decade digging through historical records such as newspaper accounts, immigration files, and shipping records, and excavating fishing camps along California’s Northern Channel Islands to unpack how Chinese fisheries were established and run. Newspapers first record Chinese abalone fishing activities in 1853 in Monterey, and in 1856 along the Channel Islands; the fishers were either immigrants who abandoned the gold industry or new arrivals who had heard rumors of untapped riches on California’s coast.

Lacking the diving equipment to exploit deep-water species, Chinese fishermen walked rocky shorelines during low tides to gather abalone. Fishers would lift the abalone shell slightly and thrust a stick or pry bar underneath the mollusk to pop it off the rock. The viscera were discarded, and the meat, which looks something like a massive snail, was boiled for two to three hours. Once cooked, the meat was air-dried on racks and packed in canvas bags for transport.

With proper cooking, abalone is a tasty delicacy with a natural buttery and salty flavor. Sliced thinly, abalone make an excellent addition to chowders. Abalone steaks offer a texture somewhere between a grilled portobello mushroom and a rib-eye steak, but the meat must be carefully pounded until tender. Most 19th-century Euro-Americans lacked the culinary expertise to properly prepare abalone, which, when mishandled, can be as tough as shoe leather.

The Chinese fishery thrived as fishermen traversed the coast, scouring intertidal zones along the mainland and islands. Chinese fishermen were dropped off on the Channel Islands for approximately three-month intervals to collect, dry, and pack intertidal black abalone meat and shells. They often contracted with Euro American-owned steamship companies to transport their products to domestic Chinatowns and, internationally, to China. At the peak of California’s Chinese abalone industry, in the 1880s, fishermen working the Northern Channel Islands processed approximately 40 tons of dried black abalone meat and shells annually, making it a multimillion-dollar trade. With declining gold yields and depressed wages, fishing became even more profitable than many of the industries Euro Americans were attempting to control.

After the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese fishers were especially hard hit. The combined forces of discrimination, exorbitant taxes, and exclusionary legislation triggered an abrupt decline in their abalone trade. New immigrants were barred from entry into the U.S., and many Chinese fishermen aged out of the industry or abandoned the pursuit as local and state governments passed additional laws and taxes, under the pretense of conservation, to fully legislate out Chinese communities. Hundreds of Chinese abalone fishermen worked the Monterey coast in the 1850s, but by the 1890s, newspapers describe them selling their boats and ceasing their harvests, with the last of the Chinese abalone fishermen hanging on until the early 1900s.

(Photo: USC Libraries and California Historical Society)

Japanese and Euro-American fishermen quickly filled the void, grew the abalone industry tremendously, and realized massive profits. They expanded to subtidal abalone species such as reds, pinks, greens, and whites, massively increasing harvest pressure on California abalone. Abalone steaks and chowder became culinary mainstays in local restaurants and icons of coastal California culture.

Despite governmental efforts to protect and conserve the resource, heavy fishing pressure led to the overexploitation and degradation of abalone populations until their collapse in the 1990s from overfishing and disease. Today, no commercial abalone fishery exists anywhere in California. From a heyday of widespread abundance only a half-century ago, what remains is a small, tightly regulated sport fishery for red abalone in northern California (and even that is hanging by a thread).

The sordid tale of Chinese abalone fishing is a vaguely familiar one. Immigrant communities are often targets of social and political hostility in times of economic woe. Just three decades before the Irish orator Kearney cried “The Chinese must go,” American help wanted signs often included the acronym NINA: “No Irish Need Apply.”

Rather than being economic burdens, as some critics claim, immigrants are economic engines. Immigrants are almost twice as likely to start businesses in the U.S. as native-born Americans. Today, immigrant entrepreneurialism has been especially impactful in the engineering and high-tech sectors, generating billions of dollars in sales and hundreds of thousands of American jobs. And many immigrants perform the hidden jobs—in farm fields, factories, and restaurants—that drive the American economy.

All American lives are enriched in countless ways by the contributions of immigrants, and food is no exception. What would your dinner table look like without hot dogs from Germany, spaghetti from Italy, tacos from Mexico, kebabs from the Middle East, sushi from Japan, chow mein from China, and countless other examples of ethnic-influenced cuisine? In any U.S. city or along the main street of any small town, you can probably find a restaurant serving food shaped by American immigrants.

The next immigrant contribution awaits, and we don’t want to lose out. It could be a food resource right in front of us, like abalone in 19th-century California, that we might not recognize. When I walk the intertidal shoreline along San Diego, I often see gooseneck barnacles, a delicacy in Portugal, and limpets, a culinary delight in Asia, and wonder if they might be the next new thing to arrive on the U.S. culinary scene.

I hope so, because it would mean that we are still open to learning from other cultures and adopting unfamiliar foodways—that we are still holding our doors open to foreigners and asking them to come in and teach us what they know.

This story first appeared on SAPIENS on March 28th, 2018. Read the original version here.