Welcome to No One’s Watching Week, the time of the year when the readers are away, and your tireless editors have run amok. For this week only, Atlas Obscura, the New Republic, Popular Mechanics, Pacific Standard, the Paris Review, and Mental Floss will be swapping content that is too out there for any other week in 2015.

Cowboys ain’t easy to love and they’re harder to hold

They’d rather give you a song than diamonds or gold….

If you don’t understand him, an’ he don’t die young

He’ll probably just ride away….

Mamas, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys

Don’t let ’em pick guitars or drive them old trucks

Let ’em be doctors and lawyers and such

—“Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” Ed and Patsy Bruce

My sister, Jane, is childless so far, as am I. In private moments my mother will remark on this negligence, and I don’t blame her—especially not at Christmastime. Christmas is all about children: The secular institution is a consumer market where children form the center, and the religious feast is similarly baby-centric. Those of us who are not babies, or who have never given birth to one, are sometimes left on the morning of December 25 feeling redundant: peering at each other, a bit curious and a bit disappointed that everyone around the tree has fully developed motor skills and very little magic or wonder left in their eyes.

Jane and I spent portions of Christmas Day watching a looped video of our four-year-old step-nephew opening presents in Halifax, Nova Scotia. “I CAN’T BELIEVE IT!” was his response of undimmed joy no matter what he unwrapped. A plastic Gordon from Thomas the Tank Engine sent him into blithering hysterics: “I’VE ALWAYS WANTED A GORDON,” he wailed, like a collector who has spent decades scouring the gorgeous East for some rare and priceless artifact. The sister and I agreed that, like Scrooge at the end of the Charles Dickens novel, this stripling “knew how to keep Christmas well.” In books, only children and the very old have that gift, and Jane and I both regretted that we did not.

Christmas is not Christmas without children, and when children are not ready at hand, we seek substitutes, on television or via Skype or by paying more attention to the cat. (Domestic animals get a lot more love when there aren’t tiny humans around—especially over Christmas.) We also compensate by dragging out the old photo albums and re-visiting our prelapsarian selves and submitting to the countless re-tellings of the time we peed on Aunt Gertrude in the kiddie-pool, say. One particular tale from my early years remains a little vicious—at least so it seems to me—and, in the absence of toddlers pitter-pattering through the house, I took time on Christmas Eve to interview my mom about the incident, which I recall being the meanest thing I’ve ever said to her.

The story is simple—many children dream of being cowboys, some are less patient than others, and as a toddler I had been very impatient. In my view, the cowboy had all the heroic advantages of the firefighter and the cop and even the superhero, and more autonomy than all of them combined. Anyway, one day I was mouthing off at the grocery store, and my mom gave me a tiny little slap, and I went silent until the car ride; eventually we were driving home, and from the back seat I broke my silence: “Cowboys,” I announced in high dudgeon, “don’t have mommies.”

In my memory, this remark made my mother laugh, then weep a little, but mainly laugh, and then she told everyone because apparently it was “cute.” You can imagine my wounded dignity and attendant resentment.

But I also remembered guilt attached to this exchange. I had told my mother, more or less, that I had no need of her and couldn’t wait to get away. Pretty bratty, right?

My mom remembers things more rosily, though my conscience is not yet at ease.

TED’S MOM: It was December [1989] and I was eyeing Christmas presents and I was pregnant with Jane—hugely pregnant with Jane—and I was pushing you in the shopping cart in Marshall’s, buying presents for various extended family, and you were kicking me in my rather protuberant abdomen [Editor’s Note: Yes, we checked, and this is all verbatim]—you were in the cart so I was at kick-level—and I kind of smacked you on your calf and said, “cut it out,” and, total silence from then on. Anyway I loaded all the bags into the car, I put you into the child seat in the back of the car, I started the car, started driving home, and then I heard this sort of mordant pronouncement from the back seat: Cowboys don’t have mommies.

TED: You put up with so much! You have the patience of a saint.

TED’S MOM: No I don’t!

TED: You—no, you don’t. But you did put up with a lot at various points. What was the deal with my cowboy guns?

TED’S MOM: Well, guns were a major bargaining point from forever. For example, if you got potty-trained, you could have a water pistol. Which was, I must say, a very counterintuitive connection between two things. Some things that you couldn’t have you wanted because you couldn’t have them, and at pre-school they made those melamine plates where you drew on them and then they bonded them or something and then I had to pay $1.50 and you brought this plate home and you’d drawn guns on the plate, you were really proud of yourself. And then the Pinchins gave you a gun that was a pretty good imitation of a little Beretta.

TED: The black plastic one?

TED’S MOM: Yup. And grandma and grandpa were staying watching you, and grandpa walked you to Sunday school at the Baptist church, and you said, “Grandpa, can I take my gun to Sunday school?” and he said no.

TED: I still can’t believe I kicked your belly.

TED’S MOM: You didn’t kick it very hard. Anyway I dropped you off at day care one day, I remember this still, and you were wearing these blue and black checked sort of slightly baggy pants that I really liked a lot and they looked really great and I said “bye” to whoever the teacher was and then I came back, and I had black gloves on, and I just reached into your pocket and extracted this gun. I don’t think you were allowed to have guns at day care.

TED: What was it about guns and cowboys that had me hooked?

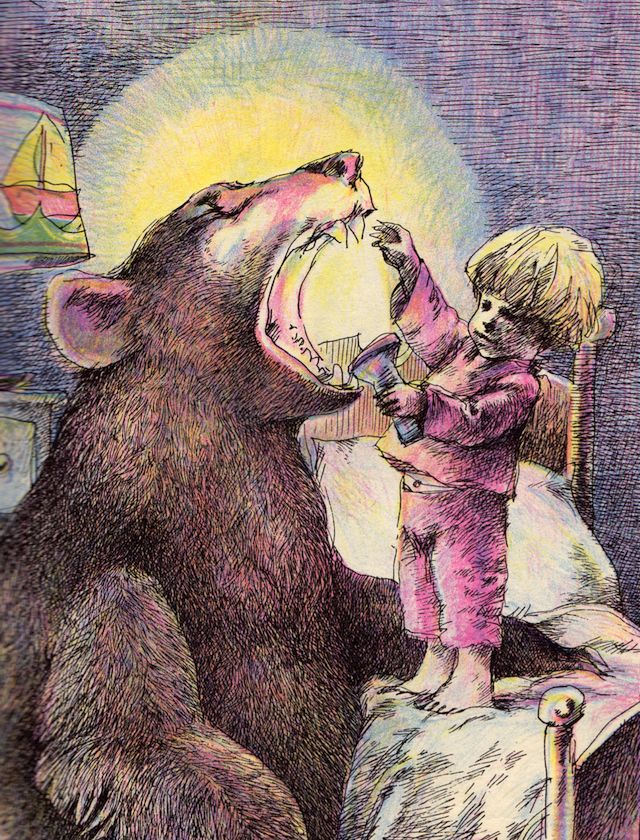

TED’S MOM: Well, in The Bear’s Toothache by David McPhail, the little boy tries to pull the bear’s tooth out with a cowboy rope, he has a lasso, so he has obviously a cowboy set. I went to a lot of trouble to find that book and I did find it and sent a copy to [step-nephew; see above]. I think that’s a wonderful book. A huge bear coming down the stairs to see if he can loosen up the tooth with some food in the refrigerator!

TED: Why did I say the cowboy line? Was that me trying to hurt you? Was that me asserting myself?

TED’S MOM: Oh, I assume it was like, “in a perfect world I wouldn’t be being disciplined by you because I’d be a cowboy,” so it was like, maybe one day you would grow up and be a cowboy and not have a mommy; I don’t know how far the thinking went—

TED: But there is that rugged notion, the Marlboro man out there on his own, he can smoke cigarettes, he can play with his plastic guns….

TED’S MOM: Oh I thought it was so funny. And also a pretty clever idea for how things could have been better, this situation, for you.

TED: That’s a pretty mean thing to say to one’s mother.

TED’S MOM: That was not the meanest thing you ever said to me.

The exchange above has been condensed only slightly—I cut out a story about trick-or-treating in a cowboy costume, as well as my mother’s very technical description of how she made the cowboy costume—but otherwise this is a frank and accurate transcription of our chat, after which I felt less guilty about having said the “cowboys” line but probably more guilty about not having sired an heir. Clearly my mother was less concerned by my own rare moments of mutiny than by the absence of a new generation of mutineers.

And that’s the real joke in the suggestion that cowboys don’t have mommies. Of course cowboys have mommies; it’s by running away from them that you become a cowboy in the first place. No mother can be truly rattled by hearing a four-year-old yearning for the plains. It means you’re doing your job—providing a civilization against which your child can define his own sense of freedom and wildness. It is a sadness to watch him ride into the sunset, but you know he’ll return as soon as he skins his knee; later, he returns with a caravan behind him, dragging the beginnings of his own family back to the original homestead, toddlers bouncing on the wagoneer’s lap, anxious for their presents and distrustful of the season, waiting in their own ways to claim temporary independence.