In the working- and middle-class neighborhoods of many Southern cities, you fill find rows of “shotgun” houses. These houses are long and narrow, consisting of three or more rooms in a row. Originally, there would have been no indoor plumbing—they date back to the early 1800s in the United States—and, so, no bathroom or kitchen.

Here’s a photograph of a shotgun house I took in the 7th Ward of New Orleans. It gives you an idea of just how skinny they are:

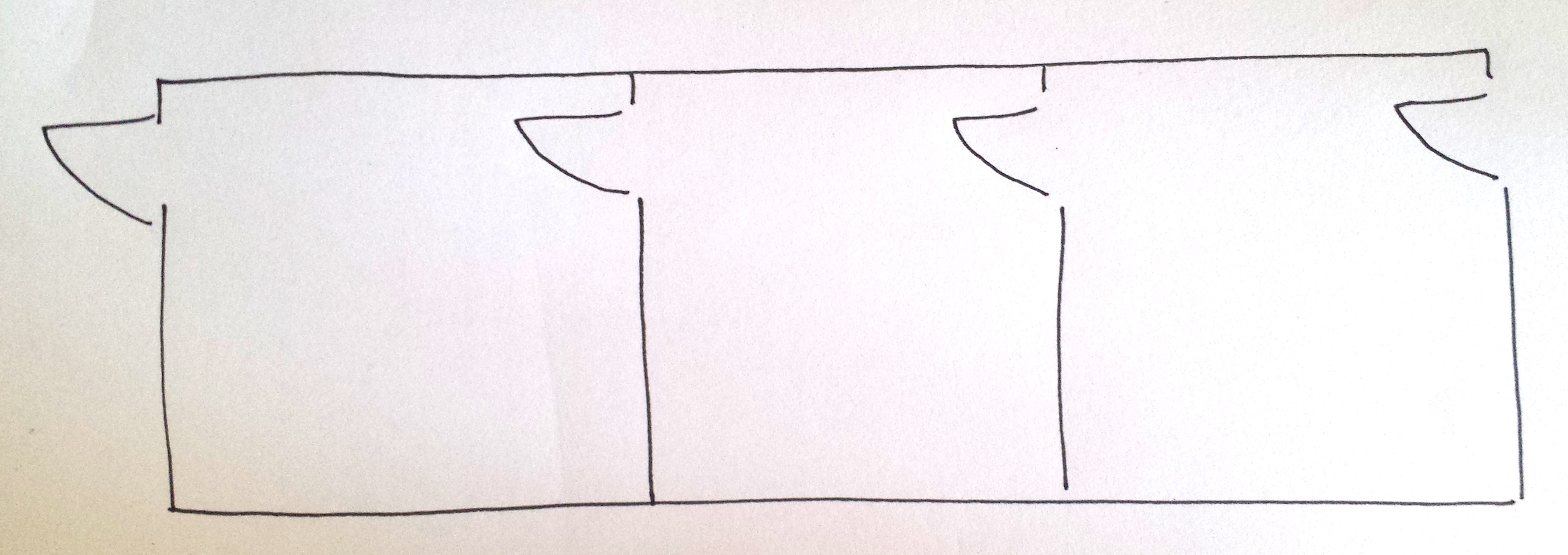

In a traditional shotgun house, there are no hallways, just doors that take a person from one room to the next. Here’s my rendition of a shotgun floor plan; doors are usually all in a row:

At nola.com, Richard Campanella describes the possible origins and sociological significance of this housing form. He follows folklorist John Michael Vlach, who has argued that shotgun houses are indigenous to Western and Central Africa, arriving in the American South via Haiti. Campanella writes:

Vlach hypothesizes that the 1809 exodus of Haitians to New Orleans after the St. Domingue slave insurrection of 1791 to 1803 brought this vernacular house type to the banks of the Mississippi.

In New Orleans, shotgun houses are found in the parts of town originally settled by free people of color, people who would have identified as Creole, and a variety of immigrants. Outside of New Orleans, we tend to see shotgun houses in places with large black populations.

The house, though, doesn’t just represent a building technique, it tells a story about how families were expected to interact. Shotgun houses offer essentially zero privacy. Everyone has to tromp through everyone’s room to get around the house. There’s no expectation that a child won’t just walk into their parents’ room at literally any time, or vice versa. There’s no way around it.

“According to some theories,” then, Campanella says, “cultures that produced shotgun houses … tended to be more gregarious, or at least unwilling to sacrifice valuable living space for the purpose of occasional passage. Cultures that valued privacy, on the other hand, were willing to make this trade-off.”

Sure enough, in the part of New Orleans settled by people of Anglo-Saxon descent, shotgun houses are much less common and, instead, homes are more privacy-conscious.

Over time, as even New Orleans became more and more culturally Anglo-Saxon—and as the housing form increasingly became associated with poverty—shotguns fell out of favor. They’re enjoying a renaissance today but, as Campanella notes, many renovations of these historic buildings include a fancy, new hallway.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Culture and Privacy: A Sociology of the Shotgun House.”