CALATEPEC, MEXICO — It was May 3rd, 2017, 72 hours shy of Mother’s Day in Calatepec, a 361-person town two hours north of Puebla, Mexico, and Guadalupe Escobar was being disciplined. Sitting in a tiny classroom at the Jaime Torres Bodet Secondary School, the 14-year-old—”Lupita” to her family—felt shunned. Her teacher, Laura Elena Juárez, didn’t find her fit to participate in the school’s celebratory essay reading, and most of her class was outside enjoying festival music. Instead, she was given menial tasks in her classroom.

About 15 minutes in, according to her later account to Puebla authorities, three fellow classmates, boys she’d known for most of her life—identified as Angel N., Juan Diego N., and Arnaldo N.—walked into the classroom unannounced. One of them locked the door. Lupita didn’t know what was going on. Was the Mother’s Day activity over already? Were they assigned to help her?

The three boys walked up to where Lupita was sitting and pulled the desk chair out from under her. She fell. Two grabbed her hands. “If you leave we will kill you,” one of the boys reportedly said. One bit her chest, under her uniform, while one held her hands against the desk. Another unpocketed his phone and started taking photos. According to Lupita’s testimony, this is when she was raped by two of them.

A pair of third-year students walked by, and saw what was going on, and proceeded to kick the door open. Lupita used the distraction to put on her clothes. She ran out crying.

Minutes after the incident, Lupita went to both Juárez and the school director, Luis Gabriel Mirón, for help. But to little effect: She was ordered by both of them to keep quiet.

Two months passed before Lupita told her mother, Sonia, what exactly had happened to her that day. She had been keeping the incident a secret out of fear of retaliation, worsened by taunting from the boys at Jaime Torres. This led to nightlong episodes of hair pulling, cutting her arms, and oversleeping (she would later see a psychologist in Tlatauquitepec). The boy’s families had caught wind of Lupita’s accusations about their sons, and were daunted. When Sonia discovered what had been transpiring, she felt incredulous that Juárez hadn’t supported her daughter after a crime so awful. Sonia confronted Juárez, demanding an explanation. She was given the same response. “She said: ‘Be careful and do not come back to the school. Look what problem you’ve put us in. They’re going to close the school because of you. I’m going to lose my job because of you,'” Sonia told independent news site Lado B in April.

There on, matters only grew worse. All three parents of the accused boys delivered steep threats to Sonia and her family. They were told to leave Calatepec and not come back. Lupita’s horror was now her mother’s, only waiting to be furthered in a court of law. In July of 2017, Lupita went with her mother to Tlatauquitepec for a medical assessment, to look for signs of rape. Tests came back positive. Optimistic, she and Lupita traveled by bus to Puebla to the Tribunal Superior de Justicia to officiate her case against the school. There, they were denied access to all court documents, even the photos the boys had taken. Off that, a second, court-mandated pap smear of Lupita came back negative. The prosecutor accused the girl of manufacturing a crime: She “had only been touched,” not penetrated. Lawyers warned the case was now flimsy. A year had passed since Lupita’s rape, and justices denied a case based on the lack of stiff evidence. And since January, Lupita and her family have been in self-exile from Calatepec. They’ve not been back since.

“They destroyed her life, my life,” Sonia told me in May. “This is a girl now filled with fear. She’s frightened. Sometimes Lupita tells me things would be better if she would have just kept quiet.”

Without a strong response on the part of the Mexican government to combat the rampant presence of violence against women, cases like Lupita’s are too frequent, according to gender activists, a mere drop in a hailstorm (an estimated seven Mexican women were killed a day back in 2016). Thus, for many families the question isn’t just, “How do I pursue a sense of justice in my society?” but also, “Who’s going to believe me regardless?”

On April 25th, 2018, 34-year-old Natalí Hernández Arias and I stand outside of the Fiscalia General de Estado, a sky-blue two-story building in Puebla’s Centro neighborhood used for prosecuting criminal cases involving the state. Today, we’re here for a meeting with Sonia, Lupita, and their two lawyers, and we’re a bit late. For at least 30 minutes we idle in the lobby: the security guard won’t let us in. Arias argues in Spanish, and only after the interplay we’re given clearance to pass together. I ask why. “He thought I was a victim,” Arias explains. “And I couldn’t go up alone.”

Today, Arias’ work as an activist is cut out for her. For nearly 14 years, she’s been fighting for a swath of victimized women around the state, currently as an ambassador for human rights organization Cafis A.C., which was founded in 2015. In August of 2013, she helped petition the state to label the murder of 22-year-old Araceli Fulles a femicide—the first state-acknowledged—through a series of protests and repeated lobbying. She’s driven hours to small municipalities to comfort mothers of kidnapped children; to Mexico City to fight for sensible abortion rights; to Puebla’s city hall to present a tough-worded recommendation for a Gender Violence Alert (a set of measures to tackle El Feminicidio, as it’s known here). Last September, Arias approached the Secretaría de Seguridad after 19-year-old student Mara Castilla was killed a mile or so from the hotel where a Cabify driver had raped her—one of the largest cases of femicide to rock the country. As for any explanation, Arias believes there’s this underlying belief of male permissibility underplaying most, if not all, of Mexico’s gender crimes.

“Mara’s case was proof that even an ordinary man can do this,” she said. “No need to be sick, mentally unstable. The important part is that these men think they can assault you without any punishment. They’ll go free, and nothing will happen.”

In an unlit office at the Fiscalia, we finally meet with Sonia and Lupita, and Arias shifts into her role of psychologist and justice-driven policy-navigator (she never received any fee from Sonia or her lawyers). For the umpteenth time, Sonia details the incident of May 2017 to the official at the Fiscalia for a preliminary meeting before a court hearing. Lupita sits quiet by her side in a pink hoodie, along with her two attorneys. She starts tearing up at the recollection. Sonia’s lawyers ask me to leave, so I wait outside in the plaza. After nearly two hours, Arias returns with a sour visage. Something went wrong. There was a problem.

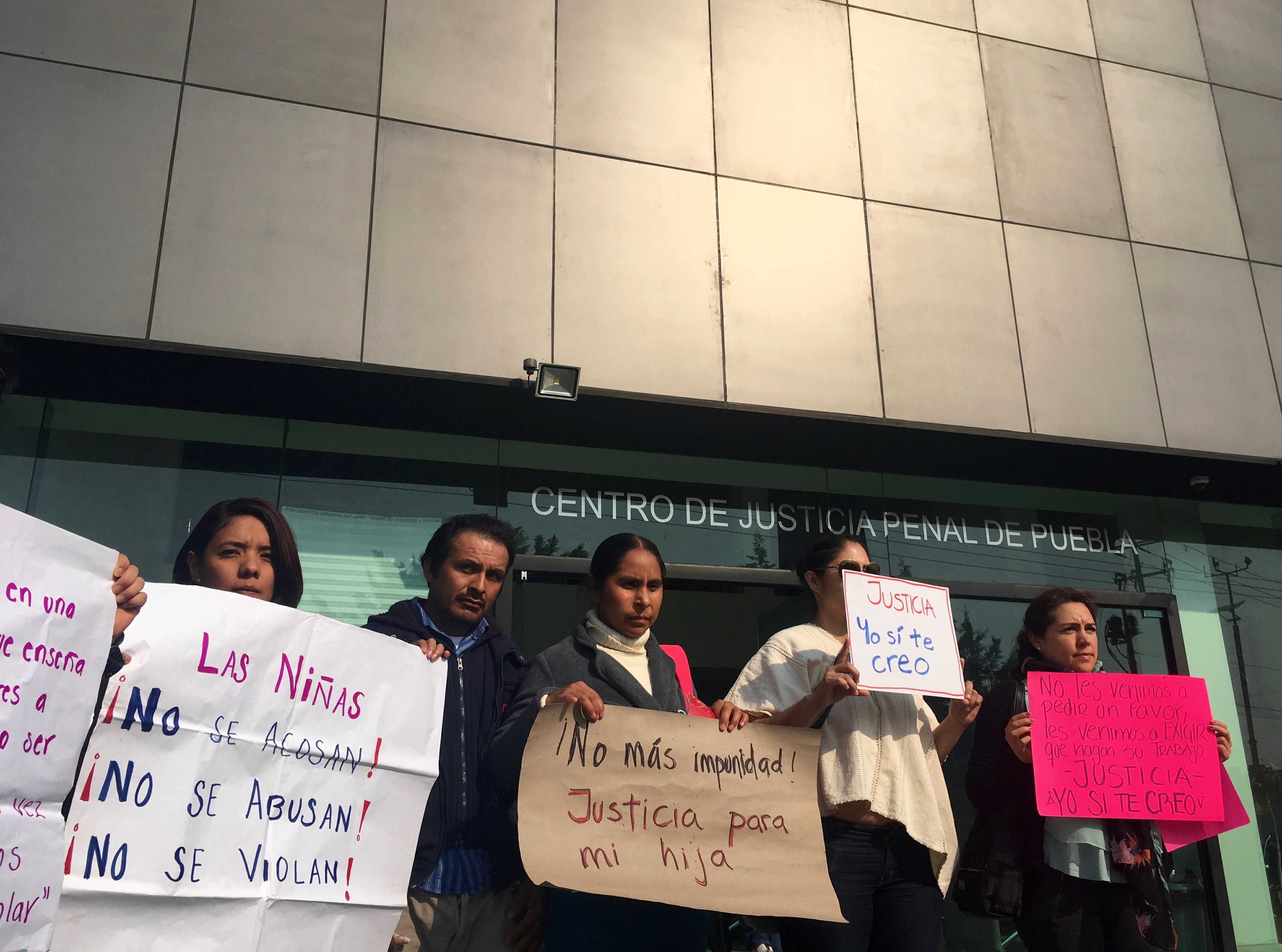

(Photo: Mark Oprea)

“The Fiscalia claims Lupita said there were four boys, not three,” Arias says. Her usual soft-spokenness turns sharp, as she explains how Sonia’s case is now faltered by the belief of contrasting evidence. Also, Sonia’s husband, a farmhand, was reportedly “threatening” Juárez when he arrived at the school sidearming a machete (a common sight for campesinos in the pueblitos).

“They’re always like: ‘You have the guilt. You are guilty all the time!'” Arias adds. “I told them: ‘You’re not alone in this. You have to believe in yourself, and your words and what you’re saying.’ That you’re not lying. That you’re made out to be a liar.”

Lupita and her mother get into a taxi to go to their new home in Tlatlauquitepec, the fifth or sixth time they’ve made this trip this year, among others for psychologists and doctors. Lupita in her pink backpack makes her look like she’s on recess. Outside, the lawyers meet up with Natali and I, and exchange banter about what just happened. (Shortly after the meeting, Sonia would decide to scrap these lawyers; she felt like they didn’t believe her.) I ask one of the lawyers to explain, and her eyes go serious under her large sunglasses.

“It’s possible there are inconsistencies with the case,” she says. “Que no hay violación.”

Five days before the meeting at the Fiscalia, in midst of Sonia’s case, Arias and 10 other feminist activists walk one clear-sky Friday to the third floor of the Centro Integral de Servicios de Puebla, a modern-styled government building. With Arias is Mariel Cortés, a coordinator from Odesyr, a human rights coalition; and Gabriela Cabrera, a short-haired founder of El Taller, the first LGBT advocacy in Puebla. They’re the who’s-who of Mexican feminists, armed with laptops and notepads, set to petition the secretary of crime prevention, María de Lourdes Martínez, to implement all “11 Recomendaciones” for a Gender Violence Alert. It’s the first time ever they’ve gotten such a confrontation.

For about two hours, the activists run through the details of the recommendations: two million pesos allotted for “a state diagnosis on all modalities of violence against women,” to financing future campaigns like “Deja de Guadar el Secreto,” and publicly admitting femicides in the activists’ definitions. For clarification, last September, the Fiscalia replied to a Cafis request to acknowledge 114 “criminal types of femicide” in Puebla since Araceli’s in 2013. According to the 11 activists, and to local think tanks, there have been more than 300.

“Although we understand your points, we don’t have any position on the matter,” Martinez says to the 12 of us, 15 minutes in. “There’s not much we can do anyway. The alert is all up to the federal government. Not us.”

After the meeting, Arias and the activists gather out on the plaza without a clear vision of Puebla’s future: Will the government ever truly accept that gender violence is much worse than is being claimed? When I ask Arias how she feels, she responds: “Estoy muy enojada.” Angry.

At the end of April, Arias and half of the activists present at the meeting with Martinez convene in front of the Centro de Justicia Penal, across the street from a four-lane highway and the Plaza Centro Sur. It’s an hour before Sonia’s first hearing with a judge and jury, where her lawyers will present the case to a circuit official. Signs from activists read, “No hay justicia!” and “Yo si te creo!” Without Arias and her associates, it seems, there would be no need for a media frenzy. No big story to tell.

After she interviews with reporters, I ask Sonia what it’s like to have activists here, picketing en masse, for no reason except for solvency. Her dark eyes water, her voice shakes.

“They give me strength,” she says. “And they give me courage. I feel stronger because of them. To move on. That I will be able to fight against anything that comes.”

After two hearings at the Centro de Justicia (the boys didn’t show up for their hearing in April), Lupita’s case still isn’t entirely settled. Puebla’s attorney general said in a statement that it’s “investigating the alleged sexual assault” of the three boys “identified as likely responsible for the incident.” According to the statement, Lupita’s teacher has been let go, and her director received a sanction. As of the middle of June, the three boys have been convicted in front of a judge, though they’re too young in Mexico’s justice system to receive stiff jail sentences. In Arias’ eyes, this is enough to remind her why she works. Why she confronts a culture so against her very being. To see it all evolve.

“Many times I have little hope for change,” she says. “I feel sad, frustrated. Then there are these small things. Hay cosas bonitas. Things that remind you that, all along, your hope rests in the same women you’re fighting for.”