More than 200 climbers are entombed in the ice on Mount Everest. When wind clears the snow away, clothing and limbs sometimes surface like saplings in a spring thaw. You can tell the older victims by their mid-century ice axes and crampons. The latest are recognizable by their branded parkas and iPhones, still loaded with text messages and snapshots.

The 2011 climbing season drew its usual clientele of rich mountaineers, and it left four more dead, at least one of whom had been trading messages with his office until days before his death. A goateed Irishman of 42 with the gaunt, taut look of a fitness obsessive, John Delaney ran the Dublin-based betting site Intrade, a playground for speculators whose interests extended beyond sports and stocks. At the time, Intrade allowed users to bet on the outcomes of a wide range of events—elections, legal cases, TV talent shows, hurricanes—and to buy and sell their bets using a dynamic stock market-like interface.

Like all bookmakers, Intrade rewarded the prescient. But to the outside observer, it also offered an abundance of exceptionally responsive, fine-grained predictions about current affairs. The site’s collectively generated odds, the reflection of a cacophony of amateur bets, often turned out to render uncannily accurate forecasts of world events—more accurate, even, than the predictions of highly trained experts.

“The problems that Intrade has had are problems that any company could have that suddenly loses a strong CEO who left, unfortunately, incomplete business records,” Bernstein says.

Some economists, especially libertarians, saw Intrade as a sign of markets’ superhuman ability to predict the future. Others saw it as a laboratory for studying the quirks and limits of prediction markets themselves. Investors poured money into the company. And presiding over all of this—the virtual casino itself, the libertarian technocrats, the market behavioralists, and the curious public—was Delaney.

He was a man of consuming intensity. He worked late, then showed up at his health club in the dark hours of the next morning so he’d be first on the treadmill. But in public, John Delaney, CEO, was a cool technocratic presence. He made the rounds on cable news during U.S. election years, calmly explaining in his Irish lilt that the predictions made by Intrade were not his own—he was just an accountant reporting the numbers, not a political expert—and that the numbers should be trusted more, not less, as a result.

As someone who watched odds for a living, Delaney probably knew that by going to Everest he faced a serious risk of death: around 1.3 percent, about the same as that of a U.S. soldier fighting in the First World War. Already he had tried and failed to summit the mountain once, in 2007, due to bad weather. On May 17, 2011—the day he left base camp, at 17,700 feet—he was optimistic, judging by the text messages he sent to his colleagues, his two kids, and his wife Orla, who was 38 and eight months pregnant.

Four days later, Delaney and his Sherpa set out for the peak from their highest camp, a rudimentary facility at 27,000 feet. They began climbing after dark, to take advantage of the overnight hardening of the snowpack and to leave enough daylight to get down safely. Like most climbers on Everest, they anticipated that it would take 10 hours to summit, followed by a half hour or so to bask in glory at the top, snapping photographs, shivering, and huffing canned oxygen.

Delaney climbed fast. His decades as an ultramarathoner and health-food nut were paying off. “They were going very, very strongly,” says Mingma Gelu, a Sherpa with the climbing club Delaney had hired. After leaving camp, the climbers surmounted a few technical challenges. But the last few hundred feet of Everest are a gentle slope. “They already crossed all the dangerous parts. He was very strong,” Gelu says. Then, without warning, 50 yards from the finish, Delaney paused and crumpled to the ground. “They couldn’t go up, and they couldn’t go down,” says Gelu. Three days later, the club posted a message on its website:

John who was a climber on the 7summitsclub’s Everest climb ran into difficulty at 8800 mts. Guides and sherpa’s asisted John but he was pronounced dead at 0430 on 21st May 2011 by guides.

Delaney has been dead now for more than two years, and his collapse was soon followed by another: In November 2012, the U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission, a federal regulator, sued Intrade for operating an unlicensed futures market that catered to Americans. The move prompted Intrade to effectively bar U.S. citizens—who accounted for 75 percent of its user base—from placing bets. Then, in March of this year, in a cloud of half-explained circumstances, Intrade shuttered its markets altogether. Among other things, an audit of the company’s books, obtained and published by the Financial Times, had found “insufficient documentation” for $2.6 million transferred from the business into accounts held by Delaney himself.

In fairly rapid succession, the highest profile prediction market in the world saw the death of its chief evangelist and then the flatlining of its operations. But the collapse of Intrade is more than a story of a single company’s rise and fall. In its brief life, Intrade’s apparent mastery of the future had been held up by dreamers as a model for whole new forms of government. But with legal obstacles piling up for prediction markets in America, it looks increasingly like the dream of a certain sort of utopian technocrat is permanently on ice.

Delaney, back row with red bandana, climbed Aconcagua in Argentina—the Americas’ highest peak—in 2005. His goal was to conquer each continent’s highest summit. (PHOTO: COURTESY OF PAT FALVEY)

THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND is small and flat, with a population the size of South Carolina’s and a tallest peak of just 3,415 feet. Delaney, already a national figure, was the first Irishman to die on Everest, so his death would have been a minor tabloid frenzy under any circumstance. But the tragedy was made especially delicious for the country’s media by an environment in which all Ireland was searching for overconfident financiers to blame for the country’s economic implosion. Delaney seemed almost a caricature of an elite businessman with a utopian faith in markets and data. After his death, film crews stalked his grieving widow, steadying zoom lenses from the edge of the family’s driveway to get the first shot of the fatherless children. When I asked Dan Laffan, Delaney’s interim successor as CEO of Intrade, whether I could visit his offices a month after the death, he asked to meet instead at a downtown hotel, saying my presence in the office would prove “extremely upsetting.” The staff had been hounded by press. This reticence was new for Intrade, which had always courted public attention—and received it, far beyond Ireland.

The idea behind the business was simple: Intrade issued contracts that paid off depending on whether an event occurred or didn’t. If the event occurred (Argo to win Best Picture), the contract was worth $10. If it didn’t (Mitt Romney to win the presidency), the contract was worth nothing.

In the summer of 2011, for example, contracts that promised to pay out $10 in the event of a 2012 Romney presidential victory traded at a paltry $2.80. But over the course of the fall, as the other Republican candidates flamed out and embarrassed themselves, the Romney-to-win contract gained in value—sometimes slowly, sometimes in an instant. When Rick Perry humiliated himself by forgetting one of the federal agencies he wanted to ax (“oops”), the price of his Intrade contract fell by half in a matter of seconds. Romney’s price, in turn, ticked upward.

By Election Day a Romney-to-win contract traded for a bit under $5, just a few cents less than an Obama-to-win. Anyone who had bought at $2.80 had multiplied his money by about 1.7 in a year (provided he sold the contract before Romney’s loss, when the contract became worthless).

But Romney’s Intrade numbers were of interest not only to gamblers. For political junkies, a contract’s price represented an easy-to-read code: When a Romney contract traded for $4.60, the market was implying that there was a 46 percent chance Romney would win.

According to one way of looking at Intrade, that single number—$4.60—represented a distillation of all the available knowledge in the world at that moment concerning the state of Mittmentum. The theory behind this view is called the “efficient market hypothesis,” which is a basic principle of economics and a good reason never to try to beat the stock market. The hypothesis says, in its simplest form, that markets know what they are doing. (Needless to say, since the financial markets imploded in 2008, the hypothesis has come under severe attack.) If the real-world odds of a Romney win are in fact 53, not 46, percent, buyers will rush to buy $4.60 contracts, and the price will very quickly rise until it settles at the right number: $5.30. Markets are good at picking up information quickly and from all directions, the theory goes. Individual buyers might not know why they are willing to pay more, but in aggregate, their hunches add up to real knowledge. “When you aggregate information from a very diverse, large community, or a crowd of people,” Delaney himself said during one of his many sage media appearances, this one on CNBC, “then typically the information that you aggregate has the opportunity to be smarter than any one individual.” You may think that a stock is “overvalued” or “undervalued,” but the market knows better.

Intrade’s numbers performed freakishly well. In 2004, bettors bought and sold contract saying George W. Bush would win the presidency at higher prices than contracts for a Kerry win—even when major pollsters were confidently predicting a Kerry presidency.

The potential of prediction markets to aggregate and reveal information is so great that some have surmised they might remake whole political systems. Robin Hanson, an economist at George Mason University, has endorsed what he calls “futarchy,” a form of government that would use prediction markets extensively as a policymaking tool. If the aggregated predictions of the market are better than the individual predictions of a few appointed experts, why not let citizens bet on, rather than submit to professional opinion on, for example, which tax policy is more likely to bring prosperity?

Other scholars—the ones who saw Intrade as a laboratory—were more interested in simply using it as an instrument to find out how prediction markets tick. Intrade obliged. The company often cooperated with researchers, listing contracts for sale at their request, and Delaney was a celebrity at academic conferences, where he discussed how the markets were working. Economists had observed smaller, university-run prediction markets, but Intrade allowed the testing of hypotheses on a much larger scale, and on almost any imaginable subject. “We live on data, and when we are in a data-poor ecosystem, we die,” says Erik Snowberg, a political economist at Caltech who has studied prediction markets. Intrade gave scholars a Niagara of data.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Intrade data allowed economists to test the limits of the efficient market hypothesis itself—to find out where markets do well, and where, and why, they break down. Snowberg and his colleagues Eric Zitzowitz and Justin Wolfers observed, for instance, that across all categories, Intrade’s predictions lost meaningful accuracy when odds rose above 90 percent or fell below 10 percent—that is, whenever any event became very likely or very unlikely. (The finding could be read as a validation of work by the 2002 economics Nobelist Daniel Kahneman and his late colleague Amos Tversky, who, using different methods, showed that people are inherently bad at making predictions about very rare events—tending to either wildly downplay or overstate the odds of things like winning the lottery, getting a rare disease, or being mugged.) And one observation that surfaced again and again was that prediction markets rely on heavy trading volume for their accuracy: The fewer the bettors, the less accurate the odds.

On balance, researchers found that while Intrade’s predictions weren’t always perfect, they were nonetheless remarkably accurate in markets—like those for political elections—where trading was high. And at times, Intrade’s predictions performed freakishly well. Throughout the 2004 presidential race, its bettors priced the Bush-to-win contract higher than the Kerry-to-win, even when most major pollsters were confidently predicting a Kerry victory. The 2006 U.S. mid-term elections were another moment of Intrade glory: Its bettors predicted the winners in every race. And they picked Joseph Ratzinger as the favorite to succeed John Paul II at a time when many experts scoffed at the notion that the cardinals would elect an ex–Hitler Youth.

It wasn’t just Intrade’s ability to predict the outcomes of competitions that thrilled its advocates. Intrade also operated where there was no competition, satisfying a demand for foresight on questions that previously had no reliable forecasting industry at all. Will weapons of mass destruction be found in Iraq? Will Israel bomb Iran? The answers could alter global economics and politics—and Intrade ventured them, sometimes appearing to reflect insider information in the process. On December 13, 2003, U.S. military forces discovered Saddam Hussein in his spider hole in Tikrit. Up to that week, the Intrade contract for his capture had traded at a dismal 40 cents, indicating merely a four percent chance of his capture by the end of the year. Then, in the days before his capture became public, the contract registered unusual trade volume—driven, one can only assume, by someone who knew what was about to happen. By the time Paul Bremer said “We got him” to reporters, Intraders already knew. Anyone who bought a Saddam contract a week before had made a profit of 2,500 percent.

For serious prediction-market supporters, this kind of insider trading is a feature of the model, not a bug. To some economists, markets that aggregate not only the best amateur hunches, but also the best inside dirt, are displaying “strong-form” market efficiency—something one rarely sees in more tightly regulated settings.

“A specter is haunting the punditocracy—the specter of Intrade,” wrote The New York Times’ John Tierney in 2005. As a columnist, Tierney counted himself among the many prognosticators threatened by the prediction market. “If recent history is any guide, their collective wisdom could be a lot more valuable than ours.” Columnists in newspapers and talking heads on TV are subject to bias, wishful thinking, groupthink, and ordinary myopia. But they pay little to no price for making bad, or even preposterous, predictions (see: Morris, Dick). By contrast, gamblers in a prediction market have money at stake, and therefore a direct incentive to get things right. And not just the punditocracy but the Pentagon took notice: In 2003, the Defense Department’s blue-sky think tank, DARPA, floated a plan to set up its own prediction market to forecast threats in the Middle East. The idea was eventually scuttled. But for a while, the clear-eyed rationality of prediction markets looked ready to shape military strategy, depose tenured figures like opinion columnists and pollsters, and democratize prognostication at the same time as it perfected it.

Economists were thrilled with Intrade’s data; they could put efficient market hypothesis—the idea that markets see the truth clearly—to the test.

JOHN DELANEY WAS BORN on New Year’s Day, 1969, the son of a dairyman in Ballinakill, County Laois (pronounced “leash”), about an hour southwest of Dublin. His upbringing was unremarkable, and he chose what many would consider the dullest of financial-sector careers, that of accountant. He earned an MBA from University College Dublin, then spent eight years counting beans for a number of companies in that city, including Oppenheimer International Finance, and AIB Fund Managers.

In 2001, Delaney was recruited to be the chief financial officer of Global Sports Exchange, or GSX, a futures market for sports. (In Ireland, as in the United Kingdom, betting on sports is legal, common, and culturally accepted. There are betting parlors on every major pedestrian thoroughfare, and bookmaking firms sponsor sports leagues, teams, and even individual players.)

At the time, GSX was attempting to expand into the U.S. market, but its efforts were hampered by U.S. laws that restrict sports betting. So GSX’s then CEO, Ron Bernstein, decided that betting on non-sports events—elections, natural disasters—was the answer. It wasn’t hard to see that the move would position GSX atop a potentially huge market: “Almost any event that had a yes-no result,” Bernstein says, could be turned into a wager. And the business model seemed foolproof. GSX, like any bookie, would profit off the vigorish—the small commission charged on every bet placed. To placate American investors fearful of getting tangled in illegal sports gambling, GSX spun off the non-sports betting market as a separate operation, and called it Intrade. Delaney had joined GSX with only a casual knowledge of futures markets, but in late in 2001 he took over as CEO after just a few months with the company.

Mark Irvine, a Scottish-born friend of Delaney’s and former Intrade executive, describes the young CEO’s daily regimen in those days as starting at five in the morning with a check of all the company’s active markets, to see how traders in the Antipodes had reacted to the night’s news. Then it was off to the gym. Since adolescence, Delaney’s fitness routines had grown ever more intense. Members of his fitness club complained that during his treadmill sessions—which he ran carrying a backpack of rocks—his sneakers filled with sweat, and his every step sprayed a fetid geyser onto the machines behind him. At two o’clock on the morning of his wedding in 2005, he woke up and ran a marathon, followed on a bike by his best man, who groaned with a hangover but accompanied dutifully.

The wedding came after a period of great strength for Intrade as well. The company was accepting bets on subjects ranging from disease outbreaks to elections to Academy Award winners, and the number of active users was in the tens of thousands. James Surowiecki’s 2004 book The Wisdom of Crowds—which related dozens of stories about uncannily accurate market forecasts and the collective genius of amateurs—was a bestseller. And among the chattering classes, mentioning Intrade was becoming a mark of sophistication.

The absolute peak of Intrade’s powers may have been the 2004 U.S. presidential election season. That year, Irvine recalls, someone tried to manipulate the market by buying up thousands of John Kerry contracts, thereby raising their price and the implied probability that Kerry would win. But the Intrade system demonstrated its resilience. It absorbed the roughly million-dollar Kerry dump—and immediately reverted to the original price-point.

As someone who watched odds for living, Delaney probably knew that by going to Everest he faced a serious risk of death—about the same as that of a U.S. soldier fighting in the First World War.

Despite these successes, Intrade’s founders knew that the company was on shaky footing in America, where it operated in a moral and legal gray zone. In the U.S., Intrade presented regulators and the public with a puzzle: Was it a commodity futures market—in which case it needed to be regulated and have its books scrutinized, like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange? Or was it a gambling saloon—in which case it needed to be policed and controlled, if not outlawed completely, like online poker? Those regulatory questions were going to be resolved sooner or later. In May of 2005, Delaney seized the initiative and wrote to the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, asking the agency to regulate Intrade. Six months later the CFTC responded by ordering the company to cease and desist from soliciting Americans to trade in commodities like oil and gold.

Shortly thereafter, Congress dealt a second setback with the Unlawful Internet Gambling Act of 2006. That law, which was tacked on to a bill relating to port security in a last-minute legislative sausage-making session, forbade U.S. financial institutions from dealing with online gambling operations. Intrade executives sensibly worried that the company might be on the wrong side of this law. On the advice of lawyers, Delaney ceased traveling to the United States for fear of being arrested, and the company began erecting barriers to keep out the thousands of Americans who wanted to buy contracts—and who were the majority of its customers.

In 2008 Delaney again wrote to the CFTC, making the case that Intrade deserved oversight and legal recognition—to no avail. By the time Delaney set out for Everest in spring 2011, Intrade was hobbling.

The setbacks did not dim Delaney’s focus on preparing for the mountain. He had already conquered six of the world’s “seven summits”—the high points of each continent. And despite a 2009 surgery to remove a benign chest tumor, he was in rude health. Mindful of his failed attempt to summit due to bad weather in 2007, this time he left as little as possible to chance. Before leaving Ireland, he changed his usual diet of salads and health food, subjecting himself instead to meals that included unwashed vegetables and other foods covered with dirt. The idea was to toughen his guts and prepare him for the bowel-busting Tibetan and Nepalese camp food he would have to eat while acclimating.

Almost 4,000 climbers have reached the top of Everest, the vast majority of them in the past two decades. The cost of the trip—tens of thousands of dollars—has made it most feasible for wealthy professionals, businessmen, and CEOs like Delaney. They make up a strange tribe. Despite all their high-tech gear and the support infrastructure that has grown up around the mountain, the climb is in many respects as dangerous for them now as it was for the first men who summited in the 1950s. Biology hasn’t changed, and in the thin air above 26,000 feet—what climbers call the “Death Zone”—the body conspires against its owner in a variety of macabre ways. Massive headaches strike at random as the body, trying to maintain sufficient oxygenation, pushes extra fluid into the brain. The pressure builds up, and the brain slowly squeezes to death. In some cases, the lungs also fill with pink frothy sputum; even if your brain still works, you must descend quickly out of the Death Zone—or you will drown, five and a half miles above sea level.

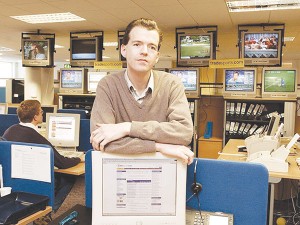

Delaney (2003) spun Intrade out of an Irish sports-betting market to get around American squeamishness about gambling. It didn’t work. (PHOTO: JOHN COGILL/BLOOMBERG)

WHEN INTRADE SHUT DOWN its markets last March, it posted a cryptic note stating that it had recently discovered “circumstances” that “may include financial irregularities.” Intrade no longer had all the money its customers had deposited with it—it was $700,000 short—and it intended to recover $3.5 million from two parties. One was reported to be Delaney’s estate. But, facing the immediate threat of a run on its remaining funds, Intrade said it would have to shut down and liquidate unless its account holders agreed not to demand their full balances back immediately. The customers agreed to forbear, and Intrade still exists—as a legal entity, not a normally functioning business.

It’s still a mystery what happened to those misplaced funds reported by Intrade’s auditors, and why they appeared in an account of Delaney’s. But it’s clear that Intrade was suffering in the months leading up to his death, and that it never really recovered. With trading volume down, Intrade’s ability to predict winners waned in the 2012 election. (Perhaps reflecting the libertarian longings of the remaining Intrade betters, the market overrated Ron Paul’s chances of winning.) The site also stopped being as valuable a source of data to economists and other social scientists. “[There] are questions that we needed data to answer,” Snowberg says. “And because of the slowdown in prediction market activity, there hasn’t been data to answer [them].”

In November 2012, the CFTC sued Intrade, saying its contracts on the price of commodities like oil and gold (will it trade above $1,400 per ounce on January 1?) amounted to illegal futures trading. Within hours, Intrade closed itself off entirely to U.S. bettors, and according to Ron Bernstein, the company lost 75 percent of its remaining accounts.

Bernstein, who helped found the firm in 2001, returned to Intrade last year to help sort out the mess. He acknowledges that the CFTC lawsuit devastated the Intrade markets: “Liquidity has to be very high for prediction markets to be valid,” he says. But he is adamant that none of the company’s current legal problems reflect inherent flaws in the prediction market model. “The problems that Intrade has had are problems that any company could have that suddenly loses a strong CEO who left, unfortunately, incomplete business records,” Bernstein says. “It absolutely has nothing to do with the fact that it was running prediction markets.”

Delaney had long claimed that Intrade was a powerful financial invention whose wisdom would be recognized once the public’s fear of new things subsided—and once regulators agreed to oversee it and grant their stamp of approval. There is plenty of history to support this idea. “Nearly all financial instruments we use today were at one point or another considered illegal and immoral,” says Hanson. Life insurance, for example, was long considered evil, because it is, effectively, gambling on human life. (And indeed, in the 19th century, when laws allowed people to take out an insurance policy on a stranger’s life, “life insurance murders” were a real, if rare, problem.) The government could have outlawed life insurance, but instead moved to regulate it. Now life insurance is safe, boring, and—most everyone would agree—socially beneficial.

Delaney wanted prediction markets to go much the same route. In his 2008 letter to the CFTC, he listed the ways in which Intrade predictions would save America money: by forecasting, say, the results of media format wars (Blu-ray vs. HD DVD) so as to help firms avoid wasteful investment; by helping Floridians prepare for bad weather; and by generally giving people the tools to navigate uncertainty. The CFTC should embrace prediction markets; “To do otherwise,” he wrote, “would be a societal travesty.” He acknowledged, too, that Intrade stood to profit from allowing the CFTC to examine the company’s books regularly and make sure it was a fair and dependable steward of its traders’ money.

Intrade was never given the CFTC oversight it sought, so it’s not clear how well the company played by the rules, including its own. For example, it forbade its employees from playing its markets—it would not be fair for them to bet if they could peek at the trading positions of other bettors—but Bernstein declines to say whether they did so anyway. If the insufficiently documented funds mentioned in Intrade’s audit do end up being linked to wrongdoing by Delaney, then it would appear that by beseeching the CFTC to regulate Intrade, he was beseeching it to save Intrade from himself.

The collapse of Intrade is more than a story of a single company’s rise and fall. Intrade’s apparent mastery of the future had been held up by dreamers as a model for whole forms of government.

ADVOCATES AND STUDENTS OF prediction markets like Snowberg and Hanson continue to think the theory behind them is sound, even if their reputation is in tatters. But the chances of another Intrade’s coming into existence are slim. Hanson points to the Hollywood Stock Exchange, a prediction market for box-office figures, as another example of the fates awaiting prediction markets. Soon after that exchange’s first success, Congress passed a law explicitly outlawing trading in movie futures.

Hanson continues to do academic research on the value of Intrade-like entities, and is chief scientist of Consensus Point, a company that sets up prediction markets for businesses seeking insight into crucial questions of future supply, inventory, and sales. (Best Buy has been a client.) But Snowberg says he has written his last paper on the subject, and believes the moment of prediction market vogue has passed now that the regulators have throttled off the data flow.

Still, Intrade isn’t giving up. Ron Bernstein says the company may try to operate in a way that would allow it to pass U.S. regulatory muster. He won’t give specifics about how a revived Intrade might work, but he suggests that the desire for status and reputation, rather than the desire for money, could motivate bets. Users might pay an entrance fee to enter a fake-money casino, and if they traded with intelligence and foresight, they could, say, put Intrade badges on their Facebook pages and brag about being super-predictors. And since users would hazard no real money, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission would have no jurisdiction over the market.

Other entrepreneurs are looking to evade the heavy hand of government more directly. The Dublin-based prediction market Predictious debuted in July. It deliberately avoids using the traditional banking system—the principal choke point for regulators—by forcing users to bet with Bitcoins, the peer-to-peer digital currency. “The U.S. blocked [dollar-denominated] transfers and could control Intrade by ordering the banks not to trade with them,” says Predictious’s founder, Flavien Charlon. “With Bitcoin that is impossible.” And he points out that the open nature of Bitcoin allows anyone to see exactly where the money is in the accounts, and whether there is any fraud. Predictious has only seen a few tens of thousands of dollars of bets placed, and Bitcoin has problems of its own (most damning, its extreme volatility). But the market is still young, and it will be harder to legislate out of business than Intrade.

Delaney appeared in public often, calmly professing Intrade’s freakishly accurate predictions. But is accuracy what people really want?

WHETHER THE REVIVED INTRADE or Predictious succeeds may depend on how their legal issues resolve. But there is also the unsettling possibility that they will fail because the product they deliver—accurate predictions about the future—is not a product people actually want. For all its promise, Intrade never expanded its user base far beyond the niche world of gamblers and hobbyists, and its employee head count never rose above double digits.

Startlingly little of the bounty once expected from prediction markets has materialized. John Zogby and the people at Gallup still have jobs, and inflict their numbers on us every day in the newspaper, even though their track records of prediction are awful. Meanwhile, one of the most accurate political predictors in history is fending off creditors, and the visions of futures-market utopians still sound like science fiction.

It’s perhaps no great surprise that we haven’t embraced Hanson’s “futarchy.” Our current political system resists dramatic change, and has resisted it for 237 years. More traditional modes of prediction have proved astonishingly bad, yet they continue to run our economic and political worlds, often straight into the ground. Bubbles do occur, and we can all point to examples of markets getting blindsided. But if prediction markets are on balance more accurate and unbiased, they should still be an attractive policy tool, rather than a discarded idea tainted with the odor of unseemliness. As Hanson asks, “Who wouldn’t want a more accurate source?”

Maybe most people. What motivates us to vote, opine, and prognosticate is often not the desire for efficacy or accuracy in worldly affairs—the things that prediction markets deliver—but instead the desire to send signals to each other about who we are. Humans remain intensely tribal. We choose groups to associate with, and we try hard to show everybody which groups we belong to. We don’t join the Tea Party because we have exhaustively studied and rejected monetarism, and we don’t pay extra for organic food because we have made a careful cost-benefit analysis based on research about its relative safety. We do these things because doing so says something that we want to convey to others. Nor does the accuracy of our favorite talking heads matter that much to us. More than we like accuracy, we like listening to talkers on our side, and identifying them as being on our team—the right team.

“We continue to have consistent results and evidence that markets are accurate,” Hanson says. “If the question is, ‘Do these things predict well?,’ we have an answer: They do. But that story has to be put up against the idea that people never really wanted more accurate sources.”

On this theory, the techno-libertarian enthusiasts got the technology right, and the humanity wrong. Whenever John Delaney showed up on CNBC, hawking his Intrade numbers and describing them as the most accurate and impartial around, he was also selling a future that people fundamentally weren’t interested in buying.