On September 12, 1918, Dr. Royal S. Copeland put the entire Port of New York City under quarantine. As health commissioner, he needed a way to keep what looked to be a nasty influenza from infiltrating the city. During the previous five weeks, a few dozen sick passengers and sailors aboard the incoming Bergensfjord, Nieuw Amsterdam, and Rochambeau had been met by staff from the city’s health department and whisked into isolation. Although New York had a solid history on health surveillance and inspection, Copeland was not taking any chances.

But there were so many ways into America’s most populous city that perfect containment was impossible. Within weeks of the quarantine order, New York was clearly moving toward an epidemic. “On October 4, physicians reported 999 new influenza cases for the previous 24-hour period, bringing the total number of cases since the start of the epidemic to approximately 4,000,” says The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: A Digital Encyclopedia, a project from the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine. “Still, Copeland was sanguine about the situation. Putting these figures in perspective, he told the public that Massachusetts—a state with half the population of New York City—had 100,000 cases of influenza.”

Massachusetts was reeling. Although there had been cases of flu around the country the previous spring, the first serious cases were reported in Boston in August 1918. The city’s health commissioner, Dr. William C. Woodward, had closed the public schools, theaters, and dance halls; so many people were sick, makeshift hospitals had to be built to accommodate them. There was an acute shortage of civilian medical personnel because many doctors and nurses had been called up to serve in the war. Naval installations were crippled by sickness and death. To prevent the disease from spreading to the South, naval recruits from Massachusetts who would have gone to South Carolina’s Charleston Navy Yard for training were kept in place.

“Non-pharmaceutical interventions do not cure, they do not prevent. They only buy you time.”

At Camp Devens, about 35 miles from Boston, the Army was preparing men for the fields of France, but in the fall of 1918, the young and the strong were dying without leaving America. To figure out what was felling its soldiers, the military called in its finest doctors—among them William Henry Welch, the great pathologist from Johns Hopkins, then in his late sixties, who donned an Army uniform to aid the Army surgeon general.

According to historian Alfred W. Crosby, what Welch and his fellow doctors saw in the Devens morgue was “bodies the color of slate.” They were so plentiful, “the eminent physicians had to step around and over them to get to the autopsy room.”

During his inspection, Welch looked into a cadaver’s chest and “saw the blue, swollen lungs of a victim of Spanish influenza for the first time. Cause of death? That at least was clear: what in a healthy man are the lightest parts of his body, the lungs, were in this cadaver two sacks filled with a thin, bloody, frothy fluid,” wrote Crosby in the 2003 edition of America’s Forgotten Pandemic.

The soldier had died of pneumonia, a secondary infection that often followed attack by the potent flu virus. Inexplicably, the virus was more devastating to people between 20 and 40, a cohort that does not generally die of flu so readily as the very young and old.

That soldier in the morgue was only one of the 675,000 people estimated to have died of flu or pneumonia in the United States in the fall of 1918 and the winter of 1919. For comparison: Less than a fifth that many Americans died in World War I. Globally, 50 million people or more succumbed during the pandemic. Modern antiviral drugs for the flu and antibiotics for the secondary bacterial infection that causes pneumonia might have kept more people alive, as would have an appropriate flu vaccine. But the doctors of the time—working when germ theory was still young—had none of the modern drug armament. Their vaccines were useless, and they had no idea they were fighting a virus.

Influenza viruses weren’t isolated until the 1930s, and the genetic make-up of the 1918 flu virus wasn’t characterized until Jeffery Taubenberger, now at the National Institutes of Health, and his associates announced they had sequenced it in 2005. Their decade-long effort was possible only because they had archival tissue samples from 1918 flu victims, and lung tissue from a woman found buried in Alaska’s permafrost, who had all died at the height of the pandemic. Although scientists have determined that the killer of 1918 was an H1N1 virus and that it is the ancestor of the influenza A viruses that have caused all pandemics since, they still cannot pinpoint where the disease started (despite being called “Spanish” influenza) or why its victims were overwhelmingly young.

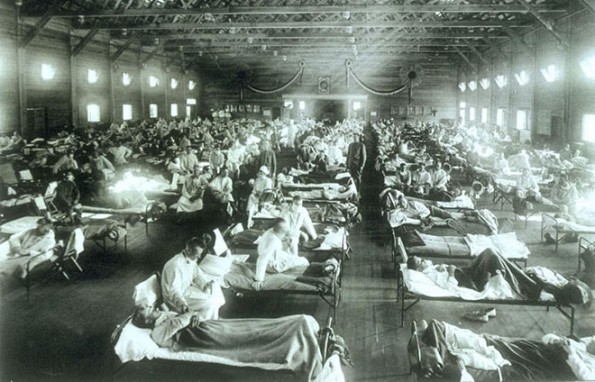

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish influenza at a hospital ward at Camp Funston. (Photo: Public Domain)

Crosby has described the physicians of 1918 as “participants in the greatest failure of medical science in the twentieth century.” But were they so powerless? Were there no pockets of hope where people averted illness and death because of actions taken by health officials? What can be learned from those practitioners of the past? Plenty, it seems.

For instance, one might expect that death rates in communities exposed to the 1918 pandemic flu would be somewhat consistent. However, research conducted in 2006 and 2007 for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by the University of Michigan indicates decisions by public officials to close schools, cancel public gatherings, and isolate and quarantine—to practice what are called non-pharmaceutical interventions—made a significant difference. “Cities that reacted early and [in a sustained way] using more than one of those three options did better in terms of mortality than those that did not,” says Howard Markel, a physician and historian of medicine at the University of Michigan.

Essays describing how the nation’s largest cities responded and fared in the face of what’s been called “the most deadly contagious calamity in human history” can be found at The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919. Markel describes the encyclopedia as “a byproduct” of the earlier CDC work, for which they had gathered a mass of great information that would otherwise have gone to waste.

Globally, 50 million people or more succumbed during the pandemic. Modern antiviral drugs for the flu and antibiotics for the secondary bacterial infection that causes pneumonia might have kept more people alive.

Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the CDC, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the site does not seem like a byproduct. It contains records for more than 16,000 newspaper articles, medical reports, and other documents, as well as images from more than 130 archives, libraries, and special collections across the country. Users can search by people, places, organizations, and subjects. Event timelines for the cities give snapshots of when the disease hit, how public health officials responded, and the disease’s impact on the normal running of a municipality.

Baltimore closed its public schools on October 8, and prohibited public gatherings soon after. From Baltimore’s timeline, one learns that cases were first reported at Camp Meade on September 24, 1918, and on October 5, 40 Sisters of Mercy and 60 fourth-year medical students from Johns Hopkins arrived to tend the sick at the camp. People who wanted to play the ponies at Laurel Park on October 21 were out of luck because racing was still suspended, even though the racetrack was an open-air venue, then generally considered to be a bit safer. The last entry for the timeline notes that March 16, 1919, was the first day since the previous September that no flu cases were reported for the city. The city had come through with 4,125 deaths.

A curious entry for October 20, 1918, on Chicago’s timeline notes that an estimated 14,000 persons gathered that day in Grant Park for a project called “Smile Film” that was meant to raise the morale of soldiers. A search on “Smile Film” yields a December 10, 1918, article from the Chicago Herald and Examiner that announced the death by pneumonia of one Rex Weber, director of “Smile Film,” whose “thirty-four reels of solid happiness” were “to greet the American soldier boys in France on Christmas Day.”

According to the newspaper account, Weber had for medical reasons been exempted from military service but had “devoted his entire energies to boost anything aiding the war.” In the family’s window, said the newspaper, “there should be a service star of gold,” a reference to the practice of hanging a gold star to honor a deceased veteran.

The January 12, 1919, entry reports that Chicago’s health department was finishing a survey of drugstores. At the epidemic’s height, doctors were prescribing habit-forming drugs such as opium and morphine. On the same day, Commissioner John Dill Robertson said that the shortage of good nursing staff had accounted for many deaths. To relieve the problem, Chicago’s Training School for Home and Public Health Nursing opened the following July. “Nearly 800 women completed the inaugural class, and within two years some 3,000 women had passed the course. When influenza returned in 1920, 600 of these graduates answered the call for volunteers, exactly as Health Commissioner Robertson had hoped they would,” says the encyclopedia.

Many of the heroes of the pandemic, says historian J. Alex Navarro, were “average everyday citizens.” Navarro, Markel, and historian Alexandra Stern, the encyclopedia project’s director, wrote and edited much of the online flu site.

Doctors and nurses worked incredibly long hours, “really putting their lives on the line,” says Navarro. People volunteered to drive ambulances, and make face masks, and care for orphaned children. “World War I was going on, and this was something they could do on the home front.”

American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards set up inside Oakland Municipal Auditorium, 1918. (Photo: Public Domain)

Yet human nature being what it is, some people came out looking worse for the experience. In San Francisco, the face mask became the weapon of choice in the city’s crusade against the pandemic. The masks were uncomfortable, says Navarro, and women complained they didn’t look fashionable. By late October, all citizens were required to wear them in public: Mayor James Rolph went so far as to say that “conscience, patriotism, and self-protection demand immediate and rigid compliance.” People who refused to wear their masks risked being fined and arrested, a threat that surely rang hollow after Mayor Rolph and Health Officer Dr. William C. Hassler were photographed by police at a boxing match not wearing theirs.

“Flu really was an equal opportunity disease,” says Navarro, which may or may not explain why there was less ethnic scapegoating than might be expected. Still, in Denver, Italians and Eastern Europeans were blamed for the continuation of the disease.

While the encyclopedia’s archives contain many interesting documents, Markel considers the U.S. Census Bureau’s Weekly Health Index for 1918-1919 the “Rosetta Stone” for the CDC project and, by extension, the encyclopedia.

To determine whether interventions by public health officials resulted in fewer deaths during the pandemic, Markel and his colleagues needed to know what exactly cities did and when they did it. They also needed reliable death data that had been collected in a standardized way, not mixed and matched from multiple sources.

The rich 1918 literature—newspapers; local, state, and federal health reports; records of military installations—allowed researchers to address the first problem, but finding the documents that would provide good numbers was a little trickier. Markel knew there were census health data, but he wasn’t able to find them at the Library of Congress, the Census Bureau, or the National Archives. He found the only known copy of the U.S. Census health indices in the basement of the New York Public Library on a microfilm reel.

The discovery was a testament to the value of old-fashioned historical library research. “Not everything is yet up on the Internet,” he adds.

The Census Bureau’s reports provided the team with weekly pneumonia and influenza mortality data for 43 cities from September 8, 1918, until February 22, 1919. Using that information and death rate data from 1910-16, researchers were able to calculate what’s called the “excess death rate” for the nation’s largest cities during the pandemic, which they presented in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2007. The concept of an excess death rate begins with the premise that every year a certain number of people will die of a particular malady, pneumonia, for instance. When the death numbers for pneumonia for a year surpass expectations, the difference is counted as excess deaths. Where there is no unusual health crisis, the excess death rate should be close to zero.

So how did the excess death rates vary from city to city? Users of the encyclopedia can find those answers by clicking on the events timeline in the individual city essays. Comparing just three cities—St. Louis, New York, and Boston—is enlightening. St. Louis had an excess death rate of 358 per 100,000. In contrast, New York’s was 452 per 100,000, and Boston’s was an astounding 710 per 100,000. What was different about the three cases?

Navarro credits Dr. Max C. Starkloff, the health commissioner for St. Louis, with acting swiftly. Starkloff was following events in Boston, and in early October decided that St. Louis should close its schools and cancel public gatherings for about 10 weeks. Business hours were restricted, a plan criticized by the local business community, and the commissioner went so far as to have policemen in department stores to keep people moving. A perusal of the St. Louis newspapers during the pandemic shows a commissioner willing to be unpopular: He shut down churches, public dancing, Halloween parties, and football games. To educate the public, Starkloff wrote for the newspapers and took the unusual step of creating a Bureau of Information.

Even with the lowest death rate on the Eastern Seaboard, New York still experienced a total of 20,608 flu-related deaths. It’s hard to imagine what the total might have been had Copeland and the city’s health officials behaved differently. “New York reacted earliest to the gathering influenza crisis,” say Markel and his colleagues in their JAMA paper. The city “rigidly enforced application of compulsory isolation and quarantine procedures” for more than 10 weeks and required staggered business hours for a month. However, unlike other cities, it did not close schools. New York also required that influenza cases be reported, and that people identified as having the flu, under its sanitary code, be isolated.

The capital of Massachusetts, on the other hand, was “one of the worst hit cities in the United States,” says the flu encyclopedia.

“In reality, there was probably very little Boston could have done to have made its epidemic less severe.” The disease was rampant before city public officials really grasped what had hit them.

The historical record shows, among other things, that well-chosen and well-timed non-pharmaceutical interventions made a difference in 1918. But how relevant are such methods now that the public health community has drugs and vaccines? Very relevant, as it happens.

Mexico, for example, in the early weeks of the 2009 flu pandemic, which was caused by a novel H1N1 virus, used public gathering bans and school closures to slow the spread of the disease, and there was a drop in cases, says Markel.

“Non-pharmaceutical interventions do not cure, they do not prevent. They only buy you time,” says Markel. They are also expensive and socially disruptive. But in the case of a deadly flu outbreak, they could delay the entry and spread of the flu virus. This might buy enough time to make a vaccine, a process that is getting faster with each passing year.

This post originally appeared on Humanities as “The Devastation of 1918.” In 2010, the University of Michigan was awarded a $315,000 Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant to support The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1919: A Digital Encyclopedia. In 2012, NEH also made a Digging Into Data grant of $124,000 to support “An Epidemiology of Information: Data Mining the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.” Nancy Bristow of the University of Puget Sound received a grant in 2003 to research the social history of the 1918 flu pandemic. Bristow’s book, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic, was published in 2012 by Oxford University Press.