When CVS Health customers complained to the company about privacy violations, some of the calls and letters made their way to Joseph Fenity. One patient’s medication was delivered to his neighbor, revealing he had cancer. Another was upset because a pharmacist had yelled personal information across the counter.

Fenity worked on a small team that dealt with complaints directed to the company president’s office, assuring customers their situations were rare. “I sincerely apologize on behalf of CVS Health,” Fenity says he’d respond. “This is not how we handle things. The breach of your protected health information was an isolated incident and we’ll do better.”

In fact, Fenity learned—partly from battling CVS over the privacy of his own medical information—that was “a lie.”

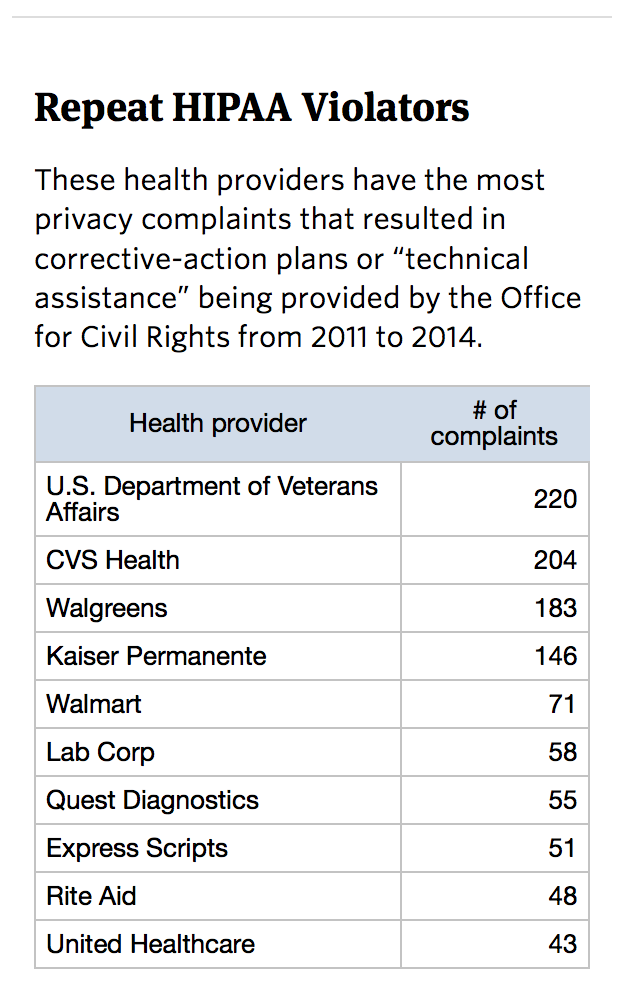

CVS is among hundreds of health providers nationwide that repeatedly violated the federal patient privacy law known as HIPAA between 2011 and 2014, a ProPublica analysis of federal data shows. Other well-known repeat offenders include the Department of Veterans Affairs, Walgreens, Kaiser Permanente, and Walmart.

And yet, the agency tasked with enforcing the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act took no punitive action against these providers, ProPublica found.

In more than 200 instances over those four years, that agency, the Office for Civil Rights within the Department of Health and Human Services, reminded CVS of its obligations under the law or accepted its pledges to improve privacy protections. (CVS did pay a $2.25 million penalty in 2009 for dumping prescription bottles in unsecured dumpsters.)

To be sure, the organizations with the most HIPAA violations are all large health care providers with many locations that serve millions of patients each year. In statements, they said they take privacy seriously. (Walmart declined to comment.)

“CVS Health is strongly committed to protecting the privacy of our patients’ health information,” CVS spokesman Mike DeAngelis wrote. “We have established rigorous privacy policies and procedures throughout the Company to safeguard patient information.”

Over the course of this year, ProPublica has reported on loopholes in HIPAA and the federal government’s lax enforcement of the law. A story earlier in December detailed how the Office for Civil Rights only rarely imposed sanctions for small-scale privacy breaches that caused lasting harm.

The data analyzed for this story shows the problem goes beyond isolated incidents, carrying few consequences even for those who violate the law the most.

“The patterns you’ve identified makes a person wonder how far a company has to go before HHS recognizes a pattern of non-compliance,” says Joy Pritts, a health information privacy and security consultant who served as chief privacy officer for HHS’ Office of the National Coordinator for Healthcare Information Technology until last year.

Pritts says the government is supposed to take into account a health provider’s prior track record of following the law when deciding whether to pursue fines for privacy violations. “You have to ask whether that’s happening,” she said.

The VA was the most persistent HIPAA violator in the data. Time and again, records show, VA employees snooped on one another and on patients they weren’t treating. One employee accessed her ex-husband’s medical record more than 260 times. Another employee peeked at the records of a patient 61 times and posted details on Facebook. A third improperly shared a vet’s health information with his parole officer.

All told, VA hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies violated the law 220 times from 2011 to 2014. For this story, ProPublica counted as violations those complaints that resulted in either corrective-action plans submitted by a health provider or “technical assistance” provided by the Office for Civil Rights on how to comply with the law.

The VA has never been called out publicly by the Office for Civil Rights or sanctioned for its string of violations.

The VA would not make an official available for an interview, but said in a written statement that it “takes veteran privacy and the privacy of medical or health records very seriously.”

“The challenges VA is facing are similar to those experienced across public and private sectors, and we are continuously striving to better protect veteran data,” its statement said, adding that it provides training to staff, investigates complaints, and conducts audits of who accesses health records.

Some privacy problems—whether inadvertent or the deliberate acts of rogue employees—are to be expected. But repeated complaints may signal organizational failures, experts say.

“I don’t think it’s a defense to just say, ‘We do a billion prescriptions a year,’” says Mark Rothstein, chair of law and medicine and the founding director of the Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. “They need to be more assertive to try to figure out what’s wrong. It may be true that you can’t get down to zero, but you need to make a really good faith effort to follow up on the complaints that were filed.”

OCR has broad latitude in deciding how to handle complaints. It can resolve them privately and informally, as it has chosen to do in the vast majority of instances. It also has the authority to impose fines of up to $50,000 per violation, with an annual maximum of $1.5 million. In the most egregious cases, the agency can file criminal charges against violators. It is free to post complaints online, if it protects patients’ identities.

Deven McGraw, deputy director for health information privacy at the Office for Civil Rights, says the agency’s top priority has been investigating breaches that affect at least 500 people, which providers are required by law to report promptly. “Often, when we take a look into those breaches, what we find is that they were not accidents,” she says. “What contributed to the breach of thousands, if not tens of thousands of records, was systemic non-compliance … over a period oftentimes of years.”

Still, McGraw acknowledges, more can be done about health providers with multiple HIPAA violations.

“I don’t like the idea of repeat offenders not being called to task for that behavior and I would like to see us doing more in this regard,” she says, adding that the office’s case management system in the past was an impediment but is now being fixed to proactively flag them.

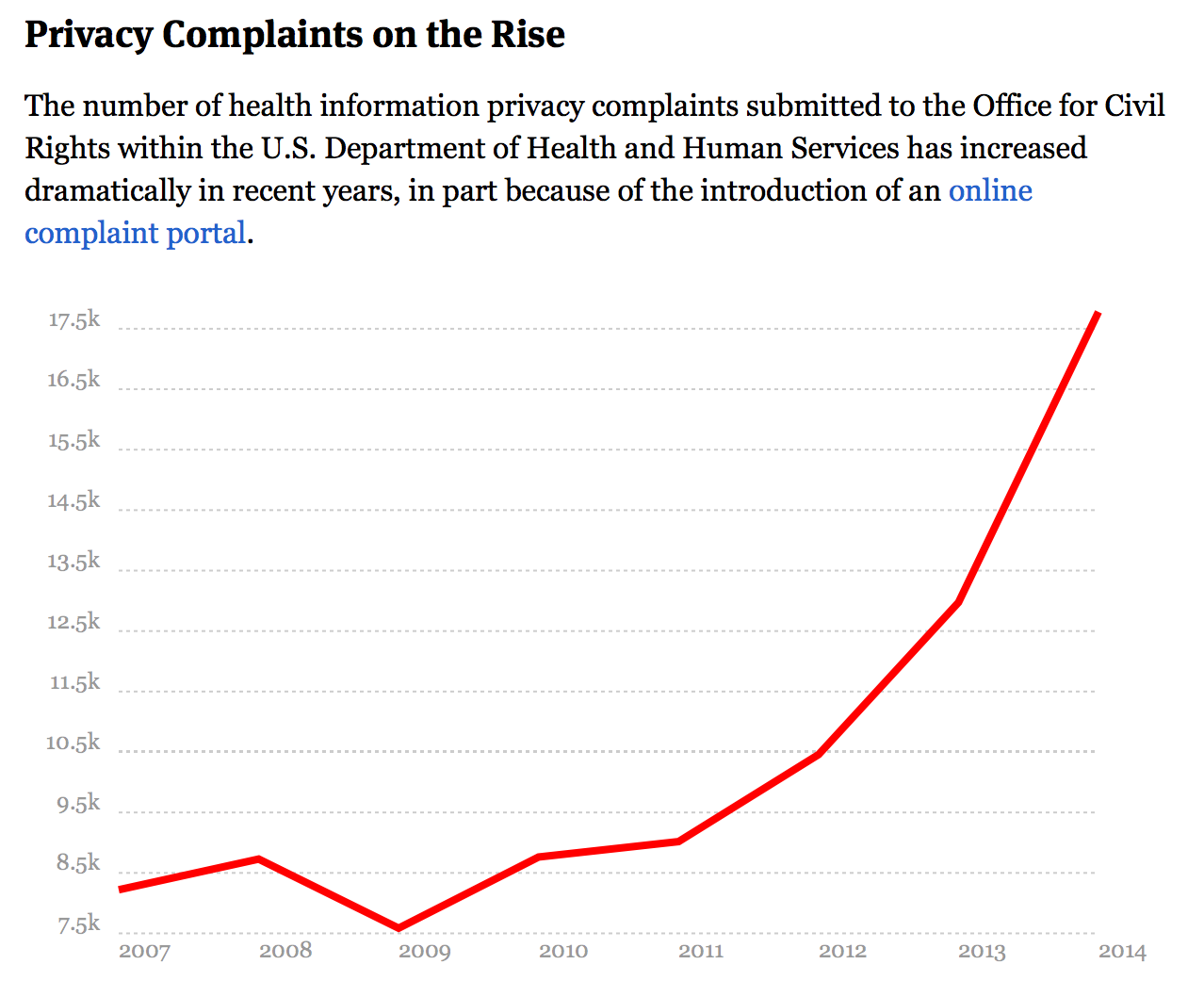

Although the Office for Civil Rights receives thousands of complaints a year—nearly 18,000 in 2014—it issues only a handful of financial penalties. The agency posts details online about the fines violators have agreed to pay (fewer than 30 since 2009), as well as a listing of large breaches. But that represents a tiny share of the incidents investigated by the office; the rest have been hidden from the public.

Asked why the office did not post details of repeat violations online, spokeswoman Rachel Seeger wrote in an email: “Entities who are the subject of complaints are not necessarily guilty of a crime or a civil wrong. Our office makes public details of cases that result in settlements and formal corrective action agreements or civil monetary penalties on our website.”

Despite the VA’s status as the top serial HIPAA violator in ProPublica’s analysis, McGraw says, “that doesn’t mean that we treat them any differently in terms of our overall enforcement philosophy.”

Using data provided by OCR under the Freedom of Information Act, ProPublica is launching a new tool, HIPAA Helper, which allows users to look up reports of privacy violations by provider for the first time. OCR’s material often referred to the same entities by multiple names. CVS was listed as “CVS,” “Pharmacy, CVS,” “Caremark, CVS,” “CVS Caremark” and more. Kaiser Permanente was identified as “Kaiser Foundation Hospital,” “Kaiser Hospital,” “Kiaser Permanente,” and even “KP.” We have standardized organizations’ names to make searching easier.

The database also includes the large breaches self-reported by health providers to the Office for Civil Rights, privacy incidents logged separately by the VA, and violations cited by the California Department of Public Health, which can impose its own fines against hospitals for failing to protect patient privacy.

Two reports issued this fall by the HHS inspector general faulted the Office for Civil Rights’ case-tracking system for its inability to track repeat offenders.

The Office for Civil Rights said it is taking steps to fix those problems.

To gain a better understanding of the nature of the complaints received by OCR, ProPublica requested dozens of letters sent by the office to health providers detailing the allegations and how they were resolved.

In the case of CVS, common complaints included giving drugs to the wrong patients, speaking too loudly when discussing health information in front of customers, and faxing medical information to the wrong places (including to random strangers).

Many of the letters culminate with the admonition: “Should OCR receive a similar allegation of noncompliance against CVS in the future, OCR may initiate a formal investigation of that matter.”

But that doesn’t seem to have happened.

DeAngelis, the CVS spokesman, says the company’s 200,000 employees who work in pharmacies, medical clinics, and call centers are required to complete privacy training when they are hired and every year afterward. That’s in addition to regular on-the-job-training on privacy practices, he wrote.

Walgreens ranked third for the number of privacy complaints resolved with corrective actions or technical assistance, ProPublica’s analysis showed. Spokesman Jim Graham wrote in an email that the company “takes the privacy and security of our customers’ information very seriously. Walgreens thoroughly investigates any concern about privacy regardless of how it is brought to our attention and will voluntarily improve practices if necessary.”

Beyond the cases in OCR’s data, there have been other incidents indicating that Walgreens sometimes struggles with patient privacy. In 2013, an Indiana jury ordered the company and one of its pharmacists to pay $1.44 million because the pharmacist looked in a patient’s prescription records and told her ex-boyfriend that she had stopped taking birth control pills before becoming pregnant. The verdict was upheld by the Indiana Court of Appeals.

Nicolas Terry, a professor and executive director of the Hall Center for Law and Health at Indiana University’s law school, says the Office for Civil Rights has moved more aggressively in recent years to impose fines against health providers that have had large-scale breaches or have done “dumb things,” such as a cardiology group that used a publicly accessible online scheduling system. Still, he says, the agency could do more.

“If you see the same offender continuing along the same line of conduct, then at some point, you’ve got to ramp up and say, ‘You are not taking the hint that we are dropping,’” Terry says.

For patients whose medical information is exposed, the effects can be far-reaching.

The breach involving Fenity occurred in September 2014, when he couldn’t re-fill a prescription for a controlled substance—a medication to treat Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—at a CVS pharmacy and called the company’s helpline (as required) for permission to get the drug elsewhere.

All CVS employee calls were routed to the center in San Antonio where Fenity worked, and he soon discovered that a co-worker who assisted with the call hadn’t kept his inquiry confidential. Walking down a hall a couple of days later, Fenity heard the co-worker mention his name and the medical lingo used to describe controlled substance overrides.

Deeply shaken, he told a supervisor and, after investigating, the company fired the co-worker and counseled two others who were told the information. Fenity remained so anxious and embarrassed by the incident that he took a leave of absence. (He was terminated this August for not returning.)

“It was incredibly difficult for me to reassure members that we would appropriately handle their [personal health information] or take accountability by working to avoid any additional HIPAA violations when I was experiencing the complete opposite,” he wrote in an email.

After trying to resolve the issue within the company, he filed a privacy complaint against CVS with the Office for Civil Rights. He said he believes the company’s systems for protecting his health data were—and still are—inadequate. It is pending.

CVS’s DeAngelis says the company investigated Fenity’s complaint promptly and fired the employee to blame.

DeAngelis also notes that employees can request that their calls be routed to a single employee who “would be the only representative authorized to access their prescription account. In fact, following Mr. Fenity’s incident, this option was offered to him and he accepted.”

Fenity can still recall the chill of realizing the information about his medication was out.

“It’s like feeling your clothes have been ripped off in the middle of work,” he says. “That’s what it feels like. You feel so exposed.”

This story originally appeared on ProPublica as “Few Consequences for Health Privacy Law’s Repeat Offenders” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.