Medical researchers are striking back against the fast-growing and oft-fatal global scourge of Clostridium difficile.

The number of Americans struck down with infections of the bacteria in their intestines nearly tripled from 1996 to 2005. The obstinate species can rise up from negligible levels in the gut after the beneficial gut flora around it die—often felled inadvertently by antibiotic treatments. Once this bad bacteria has taken over a victim’s insides it can be relentless, with 30 percent of patients relapsing following antibiotic treatment. Once a patient has been treated twice, they are more likely than not to suffer subsequent bouts.

“Freezing and banking allows us to have the stuff available, and not need to ask the patient to search around for a donor, then test that donor, which all takes time.”

A therapy has been used in recent years that could be as gross to discuss as the dehydrating, malnourishing, and desperate bathroom-hunting symptoms that the infection brings on. Awkward though it might be for a writer to broach such grossness using mild language that won’t drive away readers, the life-saving nature of a medical breakthrough described in Clinical Infectious Diseases obligates me to do my best. So here I go.

You’ve heard of organ transplants, right? Well, you may have also heard that doctors have been transplanting microscopic flora from healthy guts to ones ravaged by infection to help wipe out the bad bugs. It’s a fruitful therapy that’s been around for 50 years, but the new-found virulence of C. difficile has begun pushing the practice into the mainstream.

How do you get gut flora from one person into another? I’ll say this expression once and once only, and then you can feel safe to read the rest of the story without shitting your pants in horror: fecal microbiota transplant.

Finding a donor for this, er, flora, can be difficult and time consuming. Donors, normally relatives, must be screened for infections and parasites of their own. So American scientists set out to figure out whether banking healthy donor flora could help. They froze samples provided by five healthy volunteers, then infused the defrosted goodies into 20 patients, each of whom had endured an average of four relapses of C. difficile infection.

After a single treatment, 14 of the patients appeared to have been cured eight weeks later. Five of the remaining patients were treated again, with four of them cured. That means frozen microbes donated by five volunteers helped cure 18 people of their crippling maladies—a cure rate of 90 percent.

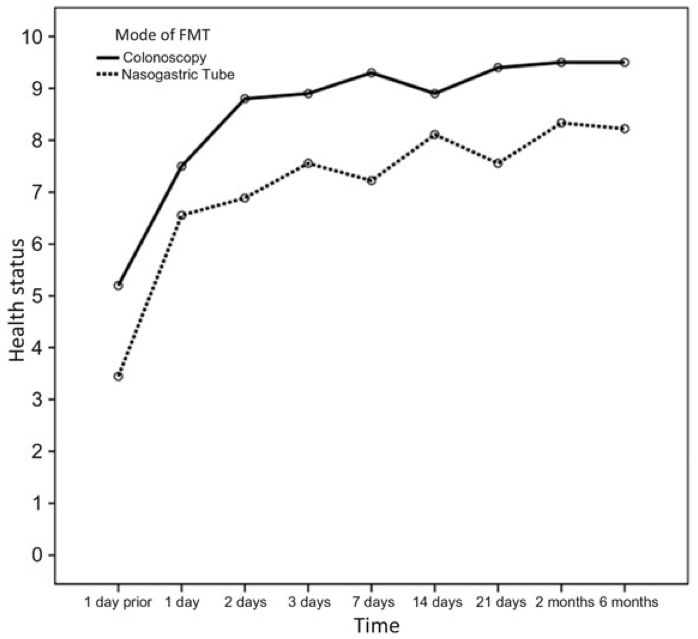

The higher the “health status,” the better the patients’ well-being. (Graph: Clinical Infectious Diseases)

The findings indicate that a donor bank for such therapies should work.

“Freezing and banking allows us to have the stuff available, and not need to ask the patient to search around for a donor, then test that donor, which all takes time,” says Elizabeth Hohmann, an associate professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital who led the study. “We can carefully screen donors and collect samples for two weeks and have enough material frozen from a single donor to treat a number of patients. It’s cost effective and simpler.”