If you’ve been to the movies recently, you may have seen one of the ads after the ads but before the other ads where the entire screen plays an action scene at a volume that only your partially deaf great-grandfather would find tolerable. Gradually, the image shrinks while the sound gets minimized and distorted until you realize you’re watching an ad for going to the movies (despite the obvious meta-irony that you’re already at the movies). The upshot: movies deserve giant screens and state-of-the-art sound, not your tiny TV screen at home.

Let’s say you buy this 70-inch HDTV for $1,500, pair it with this upscale 5.1 surround sound system for $330, and throw in another $80 for a Blu Ray player and $100 for Apple TV. If you sit roughly 15 feet from your brand new setup, this will give you a similar distance-to-screen-size ratio as sitting two-thirds from the front in a movie theater. At the average movie-ticket price of $8.16, you will have to watch 246 movies to even out not going to theaters (and that’s assuming you don’t pay for any of the movies you’ll watch at home). Unless you spend a significant portion of your waking life watching movies, it often makes economic sense to see movies at the theater.

Until we acknowledge there’s no right way to watch a movie, we’ll be stuck in a place where everyone’s being rude to someone.

Contrary to this calculation, people who spend a significant portion of their lives watching movies are precisely the ones going to theaters. Last year, according to the MPAA, 13 percent of the population accounted for 57 percent of tickets sold. The other 87 percent are either watching most of their movies at home or not watching at all. A report by Goldman Sachs analysts found that movie theater attendance per person in the United States and Canada hit a 25-year low in 2011.

As such, screen size and ticket prices aren’t enough to explain why people prefer seeing movies at home, which has led many to question the theater experience as a whole. Increasingly, asking any random person to sit still and watch a movie (even one they have chosen as fitting their entertainment preferences) for roughly two hours is asking too much, since any number of things on their phone beckon for attention.

And thus the debate over phone use in theaters. At CinemaCon 2012, a panel of movie executives debated whether it’s time to let patrons use their phone during movies. Most of the panelists were open to the idea of exploring alternatives to the absolute (but hardly enforced) no-cell-phone policy most theaters advertise, offering vague generalities about the changing nature of social engagement and attention spans. (Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf Of Wall Street—with its 179-minute running time—must not have gotten the message.)

The lone dissenting voice on the panel was Tim League, the founder of Alamo Drafthouse (a chain of 14 theaters in the U.S.), who has the opposite opinion of why the theater experience is driving customers away. League believes it’s not the absence of cell phone use that curtails attendance, but the abundance of it. As a result, Alamo Drafthouse has perhaps the strictest policy in the country, which League described to me over email as: “We will warn you once. If you persist, we will kick you out without a refund.” Of course, Alamo isn’t trying to lure people in just to kick them out. With Alamo’s consistent expansion—League told me “our business is great”—he believes he’s found a way to bring people back to the theaters.

IMPLICIT IN THE MOVIE THEATER theater etiquette debate is the imbalance of power: a tiny minority can ruin the experience for everyone. This may seem like a new problem—every problem involving technology is perceived as unique to its time—but the debate over how to act in movie theaters is as old as movie theaters themselves. In his book Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture, Peter Kobel details the first instances of movie culture etiquette:

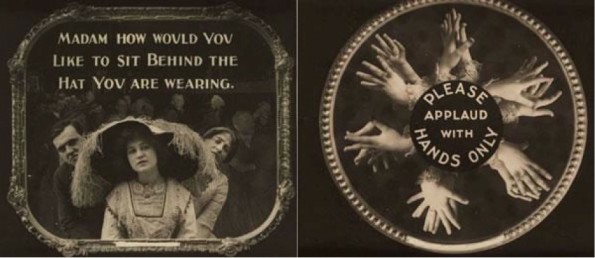

Glass slides (or lantern slides, as they were originally called) were used as pauses when reels were being worked on or changed. They were also known as “etiquette” slides because of the lighthearted instructions for patrons’ behavior when viewing the show.

While generations of moviegoers past didn’t have to deal with distracting glowing screens, we don’t have to deal with hats large enough to sneak in a popcorn machine. When the “movie palaces” came to the U.S. between the 1910s and 1940s, a debate ensued over the appropriate attire to match the lavishly decorated interiors. Going to the movies used to be “a dress-up occasion,” wrote Ron Grossman in a 2012 flashback for the Chicago Tribune. The problem is not that technology has outpaced etiquette, but that people don’t abide by it.

According to a 2009 study by University of Arkansas-Little Rock professors Janet L. Bailey and Robert B. Mitchell, 97 percent of college students surveyed found it rude to take a call in a movie theater during a movie, but 24 percent had done so. Of course, this contradiction is not at all exclusive to movie theaters. In the same study, almost 90 percent of participants found it rude to answer the phone in a library, yet almost 50 percent admitted to committing the ethical faux pas.

There are still PSAs—ohsomanyPSAs—that try to convince people to abide by the most basic social considerations during a movie. If you’ve patronized a theater recently, you know they tend to be ignored, so other methods have been explored to mandate theater ethics; cell phone jammers were briefly considered until the FCC banned them because they prevent emergency calls. Hence, the strict policy at theaters like Alamo Drafthouse.

While there are those who might not agree with League, some, in fact, have the complete opposite opinion. Perhaps most infamously, a venture capitalist doesn’t want to make his living room more like a movie theater, but vice versa: Hunter Walk wants Wi-Fi and computers permitted at theaters so he can “look up the cast list online, tweet out a comment, talk to others while watching or just work on something else while Superman played in the background.”

Although this vision is anathema to League’s theater utopia of quiet patrons enraptured in the glow of a really big screen, their underlying concepts share something fundamental. Walk wants to “segregate us into environments which meet our needs.” League told me regarding his strict policy: “The folks that are kicked out sometimes don’t take it very well. That’s fine with us. They can find another theater to frequent.”

Ultimately, they have diametrically opposed visions of the ideal movie theater but the same solution: find somewhere else. This is only a debate about ethics because the current theater system mandates we share a singular vision of theater decorum. Some people might avoid the movies because they can’t use their phones—or don’t feel like being publicly shamed for doing so—while others are sick of playing the enforcer and/or want to enjoy a quiet, dark atmosphere. Until we acknowledge there’s no right way to watch a movie, we’ll be stuck in a place where everyone’s being rude to someone. That is, unless we’re in our living room.