On the eastern edge of St. Joseph, Missouri, lies the small city’s only hospital, a landmark of brick and glass. Music from a player piano greets visitors at the main entrance, and inside, the bright hallways seem endless. Long known as Heartland Regional Medical Center, the non-profit hospital and its system of clinics recently re-branded. Now they’re called Mosaic Life Care, because, their promotional materials say: “We offer much more than health care. We offer life care.”

Two miles away, at the rear of a low-slung building is a key piece of Mosaic—Heartland’s very own for-profit debt collection agency.

When patients receive care at Heartland and don’t or can’t pay, their bills often end up here at Northwest Financial Services. And if those patients don’t meet Northwest’s demands, their debts can make another, final stop: the Buchanan County Courthouse.

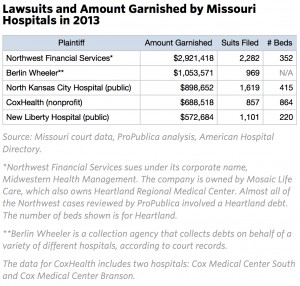

From 2009 through 2013, Northwest filed more than 11,000 lawsuits. When it secured a judgment, as it typically did, Northwest was entitled to seize a hefty portion of a debtor’s paycheck. During those years, the company garnished the pay of about 6,000 people and seized at least $12 million—an average of about $2,000 each, according to a ProPublica analysis of state court data.

Many were uninsured Heartland patients who were eligible for financial aid that would have eliminated or drastically cut their bills. Instead, they were charged full price for their care, without the deep discounts negotiated by insurers, according to court records, interviews, and data provided by Heartland. No other Missouri hospital sued more of its patients.

Even after the 2010 Affordable Care Act, about 30 million Americans remain uninsured, in part because some states, like Missouri, have not expanded Medicaid to cover more of the poor.

Blue-collar workers, Walmart cashiers, nursing home aides, clerical staffers—these types of patients have long been the most vulnerable to unexpected debt. They can’t afford insurance, yet they’re not poor enough for Medicaid. Even after the 2010 Affordable Care Act, about 30 million Americans remain uninsured, in part because some states, like Missouri, have not expanded Medicaid to cover more of the poor.

Earlier this year, ProPublica and NPR reported that the wages of millions of U.S. workers are diverted to pay off a variety of consumer debts. Most states, like Missouri, allow creditors to take a quarter of after-tax wages—an amount that government surveys show is unaffordable for lower-income families.

Consumer advocates say the laws governing wage garnishment are outdated and overly punitive, regardless of the debt’s source. But the consequences are especially dire when garnishment is used to collect unavoidable health care bills—with interest and legal fees piled on.

No one tracks how many hospitals sue their patients and how frequently, but ProPublica and NPR found hospitals that routinely did so in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Alabama, as well as Missouri. The number of suits is clearly in the tens of thousands annually. In Missouri alone, hospitals and debt collection firms working for them filed more than 15,000 suits in 2013.

Court records also revealed stark differences in how hospitals within each state pursued patients who couldn’t pay their bills. In Missouri, a handful of hospitals, Heartland foremost among them, accounted for an outsized portion of suits. But many others, including the state’s largest hospital, rarely, if ever, sued.

Heartland’s aggressive tactics aren’t because the hospital is strapped for cash. Despite being based in an economically struggling county of just 90,000, Heartland reported a $45 million profit last year and paid its chief executive $1.2 million, according to its annual report. The hospital declined to discuss Northwest’s finances.

As a non-profit, Heartland pays no income taxes and no property taxes on the acres of land it owns. In exchange for these tax breaks, it is expected to provide a benefit to the community—most crucially by providing care to lower income patients who can’t afford to pay.

Tama Wagner, the hospital’s chief brand officer, said the hospital does everything it can to fulfill that mission. Patients are offered multiple opportunities to qualify for financial assistance and avoid the possibility of legal action, she said, adding that it’s better for everyone “if we attempt to work on things before it gets to this level.”

But if patients don’t utilize those resources, she said, the hospital must take action. “No one goes into this with the goal or the desire to ruin someone’s life,” she said. “But at the same time, the services were rendered, and we have to figure out how to get them paid for.”

Asked why the hospital sues more patients than any other in the state, Wagner said, “I don’t know.”

Chi Chi Wu, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center, said Heartland’s tactics ran counter to its mission. Non-profit hospitals are given tax-exempt status “because they are supposed to be serving the public and especially the poor,” she said.

But if hospitals are charging low-income, uninsured patients “even more and then garnishing their wages on the basis of these inflated amounts,” there ought to be consequences, she said. “They should lose their tax-exempt status.”

The center has recommended that federal regulators prohibit debt collectors from garnishing wages based on the high prices hospitals charge uninsured patients.

In interviews, former patients said they’d run up debts to Heartland mostly because, in an emergency, it’s their only option. They never expected the hospital to seize their wages if they couldn’t pay.

Northwest first sued Keith and Katie Herie when they couldn’t afford the $14,000 bill for Katie’s emergency appendectomy. While Northwest was seizing Keith Herie’s pay for that suit, it sued him again over another hospital visit. Since 2006, the Heries have paid almost $20,000 and still owe at least $26,000, with interest mounting.

ProPublica and NPR shared Herie’s case and other findings with Heartland’s board of trustees, which is now reviewing the hospital’s debt collection practices.

“Make it so people can make a dent in it,” said Herie, 51, a drill operator. “There’s a lot of people who want to be able to pay their medical bills…. But they’re not going to jeopardize their household for it.”

DOCKET FILLED WITH PATIENCE

On a morning last month inside Buchanan County’s historic courthouse, the docket was stocked with more than two dozen Northwest cases.

“You have quite a few today,” the judge noted with easy familiarity to Northwest’s attorney, who last year filed more than 1,000 such suits.

In 2013, Northwest won judgments in 77 percent of its cases, usually because the defendants didn’t show up, court records show. Only three percent of those sued had an attorney. And all of the judgments tacked on a nine percent interest rate to the debt, the most allowed under Missouri law.

Most of the defendants who made it to court that day waited glumly, not entirely sure how the proceedings were supposed to go. Some had been served with lawsuits at work: Denny’s, Walmart, a pig slaughterhouse, a local charity. A woman and her daughter had both been sued.

Whether debtors show up or not, the outcome seldom varies.

Some former patients agree to payment plans to avoid garnishment. But since Northwest requires these arrangements to be renegotiated or paid “in full” after six months, the plans are not a guaranteed reprieve from court action. A Heartland spokeswoman would only say the periodic reviews were company policy.

When her case was called, Tammy Berry, who earns $8.20 an hour working at the fast food chain Taco John’s, told the judge incredulously, “They’re already garnishing my paycheck.” The judge acknowledged that might be true. But not, he said, for the case on the docket that day.

Berry, 48, and her husband Keith, 47, were first sued by Northwest in 2009. Since then, Northwest has garnished $4,500 from Tammy Berry’s pay, almost all of it going to pay off interest (Keith Berry said he does not work and is applying for disability payments). The couple still owes $7,000 on that debt. The couple has had a number of ailments including issues with Keith’s heart, but they are unclear on which led to the suits.

Court data shows that in 2013 Northwest garnished the wages of hundreds of lower income patients—including more than 50 employees of fast food restaurants such as McDonald’s and more than 100 Walmart employees.

Then, while still being garnished for those bills, Berry said she fell ill with pneumonia and went to Heartland for treatment again. Northwest sued them for $4,600 more.

Federal law only protects the poorest of the poor from garnishment, and Tammy Berry is not poor enough. If she takes home more than $870 a month, her wages can be garnished. On the weeks she works full-time, the garnishments bring her take-home pay below the minimum wage.

The Berrys had qualified for charity care at Heartland for bills at other times, so the hospital has known that their finances were precarious, yet they were charged full price for Tammy Berry’s treatment for pneumonia. Heartland spokeswoman Tracey Clark declined to explain this, but said “information has to be a two-way street.”

At the judge’s urging, the Berrys said they met with Northwest’s attorney and offered to pay $20 every two weeks. The attorney told them he was not authorized to accept such a low offer and they would have to ask Northwest directly, the Berrys said. In the end, they agreed that they owed the debt and Northwest received a judgment against them.

Outside the courtroom, the couple slumped on a bench dejectedly and said they were uncertain how they would absorb this latest blow.

“We’re living paycheck to paycheck,” said Tammy Berry.

LOW-INCOME PATIENTS OFTEN SUED

Non-profits, which make up nearly 60 percent of U.S. hospitals, have a history of aggressive debt collection.

In the early 2000s, several faced lawsuits challenging their tax-exempt status based on their use of such tactics. In 2003 the Wall Street Journal ran a series of articles detailing the frequent use of garnishments by hospitals, including the prestigious Yale-New Haven Hospital.

“When the public saw that, they were shocked,” said Rick Wade, then the spokesman for the American Hospital Association.

The AHA asked its members to review their debt collection policies. Many hospital executives were surprised by what they found and decided to revamp their practices, Wade said.

A handful of states subsequently passed laws either restricting how non-profit hospitals can collect on debts or dictating how much financial assistance they must provide.

But in most states, there are no clear guidelines, and over time, public scrutiny has faded, said Nancy Kane, a professor with Harvard’s School of Public Health. “Hospitals are not looking for opportunities to give away charity care.”

Under federal law, non-profit hospitals must offer care at a reduced cost to lower income patients, a service often called charity care. But crucial details—how poor patients need to be, how much bills are reduced, and how policies are publicized—are left to the hospital. The Affordable Care Act empowered the IRS to set new requirements for publicizing this information, but those have yet to be finalized.

At Heartland, uninsured patients with household incomes up to double the poverty line ($23,340 for a single person without dependents) qualify for free care. Those with incomes between 200 percent and 300 percent of the line (up to $35,010) are billed at a rate similar to what an insurer pays, then have their bills cut in half.

Last year, about 8,700 Heartland patients had their bills cut or zeroed out, according to data provided by Heartland. About half were uninsured, while the rest were spared full payment of deductibles or other obligations not covered by their insurance.

But uninsured patients like the Berrys who don’t receive charity care—either because they were turned down or never applied—are billed at Heartland’s standard rates, the sticker price that insurers never pay. In 2013, more than two-thirds of the accounts Northwest handled involved uninsured patients, according to data provided by Heartland.

If a patient can’t pay and Northwest obtains a judgment, it’s too late. Hospital policy says once the collection agency has “incurred legal fees” on a case, the patient is ineligible for charity care, regardless of earnings.

Charity care, Clark said, is reserved for patients who “seek it and legitimately work with us.”

Court data shows that in 2013 Northwest garnished the wages of hundreds of lower income patients—including more than 50 employees of fast food restaurants such as McDonald’s and more than 100 Walmart employees. Heartland’s Clark said that Walmart employees constituted “only 3.6 percent” of the thousands of patients currently being garnished by Northwest.

The employees of a local pig slaughterhouse were Heartland’s most frequent target. One of the largest employers in St. Joseph, Triumph Foods processes six million hogs a year and has 2,800 employees, according to its website.

In 2013, at least 255 Triumph employees had their wages garnished by Northwest—about one of every 11 employees.

EIGHT YEARS OF GARNISHMENTS, NO END IN SIGHT

Just after Christmas in 2004, Katie Herie got sick and then sicker with sharp pains in her stomach, nausea, and vomiting. “I was running a fever,” she said. “It was bad.”

But Herie was uninsured, so for four days she held off going to the hospital. Finally, she said, “enough was enough.”

Her appendix had ruptured. Surgeons operated at 2 a.m., Herie recalled. After four nights at Heartland, she was discharged. The pain was gone. But in its place was a bill for more than $14,000—including a charge of nearly $3,000 for the room alone, according to court records.

At the end of each year, BJC writes off tens of millions of dollars in bad debt it believes comes from low-income patients who should have received charity care.

It was a staggering debt for the Heries. At the time, Keith Herie worked as a truck driver, earning around $30,000 annually, and his job didn’t come with insurance. The couple had two young children.

When the surgery took place, Heartland’s financial assistance policy restricted aid to those with household incomes below the federal poverty level. For a family of four, that was $18,850, so the Heries didn’t qualify.

Monthly payment plans were also out of reach, they said. Heartland’s guidelines state, for instance, that balances up to $5,000 should be repaid within 18 months. For a $5,000 balance, that would be a minimum of $278 per month, a sizable burden for lower- and middle-income families. There’s nothing in the guidelines about still larger balances. Patients who can’t pay the minimum may be eligible for a “special contract agreement,” but that could add on nine percent interest.

In a statement, Heartland’s Clark said the interest is added because “more operating costs are incurred the longer an account is active.” Patients have a host of options to pay, she said, including credit cards or loans “from family/friends.”

“They will tell you to borrow the money from somebody to pay the bill. They don’t care,” said Katie Herie.

Clark said records show that Northwest spoke twice with Keith Herie about a payment plan in 2005, but that he “would not commit to an arrangement.” Herie said he doesn’t recall those conversations, only feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of re-paying the debt.

So, in March 2006, Northwest sued the Heries, but not just for the appendectomy. The suit included a host of other outstanding bills, from a 2001 chiropractor bill for Keith Herie to a $10 pediatrician’s bill for their son. It turned out that Northwest handled accounts for local medical practices as well as Heartland. ProPublica reviewed hundreds of Northwest cases and almost all of them involved at least one Heartland debt.

The Heries’ total debt stood just shy of $17,000. But then came the interest. To start, there was $1,654 of “prejudgment interest,” and, for as long as the balance remained outstanding, the Heries would incur interest on it at a rate of nine percent a year.

Shortly after winning a judgment, Northwest moved to garnish Keith Herie’s pay. It did the same to Katie Herie, who had begun work at Sam’s Club. Missouri law allows Northwest to sue both spouses, regardless of who received the medical care. An operations memo for Northwest states that both spouses should be named in a suit if the balance exceeds $1,500.

Over the years, the garnishments have tracked the couple, following Keith to a better paying job, where he operates a drill for a firm that inventories coal stockpiles. Most of the time, Northwest has taken 10 percent of his after-tax pay, a break Missouri gives debtors with children.

Unfortunately for the Heries, other visits to the hospital followed—for chest pains, for the flu. For these Heartland visits, the Heries would have qualified for charity care if they had applied because Heartland had changed its policy to include patients making up to three times the poverty line. But the couple says no one told them.

In 2010, when the Heries were still being garnished as a result of the first suit, Northwest sued the couple again for $17,630, including a nearly $1,600 attorney fee and about $2,900 in interest.

Over the past several years, the Heries’ wages have been garnished almost continuously, with the money sometimes going to pay down one debt, and sometimes the other. They have chipped away, paying nearly $20,000, but still owe more than $26,000.

Northwest also has a lien on the Heries’ home, meaning that they are unable to sell it or refinance their mortgage without resolving the debt. According to the company operations memo, this is done in all cases in which the company has won a judgment exceeding $1,000.

“It’s like a never never plan—you’re never going to get rid of it and you’re never going to get ahead of it,” said Keith Herie.

SOME HOSPITALS RARELY SUE OVER DEBTS

Other hospitals in Missouri have found ways to avoid suing low-income patients.

BJC HealthCare, a non-profit, operates a chain of 12 hospitals, including Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, the largest in the state. In 2013, Northwest filed about 2,300 lawsuits in Missouri courts. BJC filed 26.

Unlike Heartland, BJC automatically slices 25 percent off its standard rates for uninsured patients and never includes interest on payment plans, said June Fowler, BJC’s spokeswoman.

Despite being based in an economically struggling county of just 90,000, Heartland reported a $45 million profit last year and paid its chief executive $1.2 million, according to its annual report.

As recently as only a few years ago, one BJC hospital often pursued patients in court. But BJC’s CEO Steven Lipstein said the chain’s new policies are both more efficient and more in line with its charitable mission. Patients who can pay a portion of their bills are more likely to, he said, if they learn about financial assistance and payment options early in the process.

Mark Rukavina, a Boston-area consultant who advises hospitals on billing issues, said many non-profits actively seek to identify low-income patients who might qualify for help because they don’t want to try to collect from those who can’t pay.

At BJC, patients are often classified as eligible for financial assistance based on factors like their workplace, job title, or whether they live in a zip code with a low average income, Fowler said. While these patients might never complete the application process and be officially granted financial assistance, the hospital does not attempt collections on the accounts, she said.

At the end of each year, BJC writes off tens of millions of dollars in bad debt it believes comes from low-income patients who should have received charity care. By contrast, in its 2013 tax filings, Heartland says that none of its nearly $17 million in bad debt came from patients who were eligible for financial assistance.

For Natalie Elardo, 44, who has also been sued twice by Northwest over debts incurred at Heartland, policies like BJC’s would have helped. Elardo had back surgery in 2000 and later received follow-up care for continued pain. She and her husband have paid more than $19,000 in garnished wages since being sued by Northwest in 2001. Their debts now exceed $80,000.

“I assume we will be paying them off until we die,” she said.

Weighed down by similar medical debts, Keith Herie has considered declaring bankruptcy, but said he has focused mostly on working his way out, piling up as much overtime as he can.

“I’ve been putting it on hold, because I keep believing that somewheres I can make a difference, I can get ahead of this,” he said.

The lawsuits and garnishments have had collateral effects. Herie’s current job provides insurance for him, and he has added his children, but there is not room in the budget to add Katie. He has nothing saved for retirement.

Recently, Herie asked Northwest for a printout of all his debts. It ran to four pages filled with rows of charges in tiny type. It made him think bankruptcy may be the only answer.

“I’m catching up to 52 years old come spring, and I don’t think I got another 10 years of this,” he said. “I’m tired. I’m just mentally tired.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “From the E.R. to the Courtroom: How Nonprofit Hospitals Are Seizing Patients’ Wages” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.