A short school bus idles in Larry Goshorn’s rain-slicked driveway. It’s 5:45 in the morning. The hard angles of Cody, Nebraska—the abandoned grain elevator, the belfry at the Methodist church, the water tower—have just begun to reveal themselves in the glimmer of dawn. A light flickers on above the back door of his small, white house, and Goshorn, a 1974 graduate of Cody-Kilgore High School, lumbers out. Come summer, when the students cut loose and the schedule slows down, he’ll move back to his ranch in the hills where the springs used to boil up several feet out of the ground. Until then, he’ll stay here, across the street from the high school and the bus barn, always nearby when the new driver quits, or another bus breaks down, or the new superintendent decides another field trip is in order. He’s wearing a flannel jacket and a camouflage hat, ready for the long and often unpredictable drive ahead.

“This will be my 17th year driving for Cody-Kilgore,” Goshorn says. “You can’t find bus drivers out here very easily. Once you find someone and send them to all the classes and stuff—they last about three trips and they quit. Some think they’re cut out for it, but they’re not.”

By it, he means the isolation. He means a county three times the size of Delaware inhabited by fewer than 6,000 people. The school district alone, despite a student population of fewer than 200, envelopes 553 square miles of grass and sand and sky, spanning two time zones and three area codes. The buses of Cody-Kilgore Unified Schools travel a combined 312 miles every day along quiet highways and country roads. And it’s not just bus drivers who are hard to come by. Recruiting and retaining staff, convincing administrators to custodians to special-education teachers to come to Cody-Kilgore and to stay, is difficult across the board, as it is for most small schools in rural America. It’s the lack of amenities. It’s the loneliness. It’s the feeling of being forgotten by a system that so often seems to prioritize the tribulations of the city. It’s the constant threat of closure, of nonexistence.

Educational Fight or Flight, by Carson Vaughan. Listen to more Pacific Standard stories, read out loud.

And so it’s surprising that Nebraska’s own Deb Fischer—who once represented this district in the state legislature and served on the board of the Valentine Community Schools less than 40 miles down the highway—cast a decisive United States Senate vote in 2017 to confirm Betsy DeVos, a staunch proponent of charter schools and voucherization, as the 11th U.S. secretary of education. If DeVos has her way, places like this will be without public schools altogether. Goshorn didn’t pay much attention to Fischer’s vote, frankly, didn’t care, and if you ask the superintendent, or the state’s rural legislators, or most any local, neither did the rest of the district. Roughly 85 percent of the county voted for Donald Trump. Fischer won re-election in a landslide in 2018, with barely a mention of rural schools or her confirmation vote.

The wipers now part the mist to reveal an empty highway, the Nebraska Sandhills slaloming in every direction, the grass still brittle and brown with winter. Less than a mile out, Goshorn turns south onto an asphalt road that slices through valleys of irrigated farmland before climbing back up and into the void, barbed wire bobbing through the hills like a stone skipping across water. Twenty minutes later, the bus rumbles past Goshorn’s ranch and the old Boiling Spring Bridge, where the Niobrara River cleaves the valley and a recent blizzard has razed the trees. And finally, 12 miles from the start, the bus whines to a stop at CSS Farms, a 1,200-acre potato farm in the middle of nowhere. Six young boys from three different Mexican families step on board. Their parents work at the farm.

“Good morning, Larry!” each one says, gripping books and backpacks. They’re tired but smiling and unfailingly polite. It’s barely 6:30. They woke before the sun.

“Good morning, gentlemen! How are ya?”

Some fall asleep. Some read. One stares vacantly out the window. They rarely study, even if they want to, given all the bumps and bends in the route. Depending on the number of migrant workers in the area, Goshorn will sometimes make more stops, but today this is it. He keeps driving, past a few scattered farmhouses, over another bend in the river, spooking a dozen white-tailed deer from the woods. It’s not the longest route in the district, but it’s often the hairiest, impassable with mud or snow. By 7:00, Goshorn will pull back onto the highway and complete his morning loop. The kids will step off the bus, eat breakfast, finish their homework, catch a few more zzz’s if they’re lucky. Goshorn will begin his next route. At 7:57, the kids will head to first period, and after the final bell rings at 4:00, they’ll gather their things to do it all in reverse. Goshorn will be ready, idling outside the building.

While DeVos and her acolytes continue their campaign for the whittling down of the Department of Education in favor of privatization (now deriding public schools as “a dead end”), small, rural districts like Cody-Kilgore, already running on a four-day week, are struggling. They recruit students from other districts, lobby teachers from other schools, dispatch drivers farther and farther away. The Washington powerbrokers like to talk about affording local school districts the freedom to innovate and pioneer new pathways to learning, but out here in the boondocks of the American education system, schools like Cody-Kilgore are forced to improvise just to keep the doors open.

Public schools used to be called “common schools.” After Massachusetts state senator Horace Mann was appointed secretary of the state’s newly created board of education in 1837, he launched a horseback campaign to inspect more than a thousand schoolhouses personally over a six-year period. What he found was a spectrum of discomfort and decrepitude—crumbling buildings, antiquated books, inadequate seating—especially in the most rural areas. One of them was so ramshackle, he wrote, even “the mice have forsaken it.” At the time, schools were funded by local taxes and extra fees charged to the parents, but without any state supervision, the results varied wildly between districts.

To ensure an equal and sufficient education, Mann lobbied for “common schools,” a system of public education with a universal curriculum and one that “throws open its doors, and spreads the table of its bounty, for all the children of the state.” His belief that a republic peopled with uneducated citizens “is the most rash and foolhardy experiment ever tried by man” echoed the earlier sentiments of Thomas Jefferson, who had drafted a bill as Virginia governor to guarantee all children—slaves excluded—at least three years of free education. The bill failed on three separate occasions, a sign of how radical the idea once seemed to a young country recently liberated from the taxation of another. Despite the resistance, the idea of a free, public education ultimately caught on, in no small part due to Mann’s many lectures and annual reports.

After the Civil War, as citizens scrambled to build new lives out West, schools were often prioritized as a means to lure more residents to their patch of the prairie. The value of public education was so inherent that the schoolhouse itself came to represent stability: the future of the community fared better with an educated citizenry—priming the pump for scholars, bankers, artists, doctors, lawyers, and merchants—and early settlers went to great lengths to ensure it. Women recruited from the East often staffed these isolated country schools, and they endured the harshest conditions, both geographically and socially. Nebraskans today still celebrate Minnie Freeman, who led her students to safety during the blizzard of 1888—known now as the Children’s Blizzard—by linking them together with twine and marching them through the blinding snow to a nearby farmhouse.

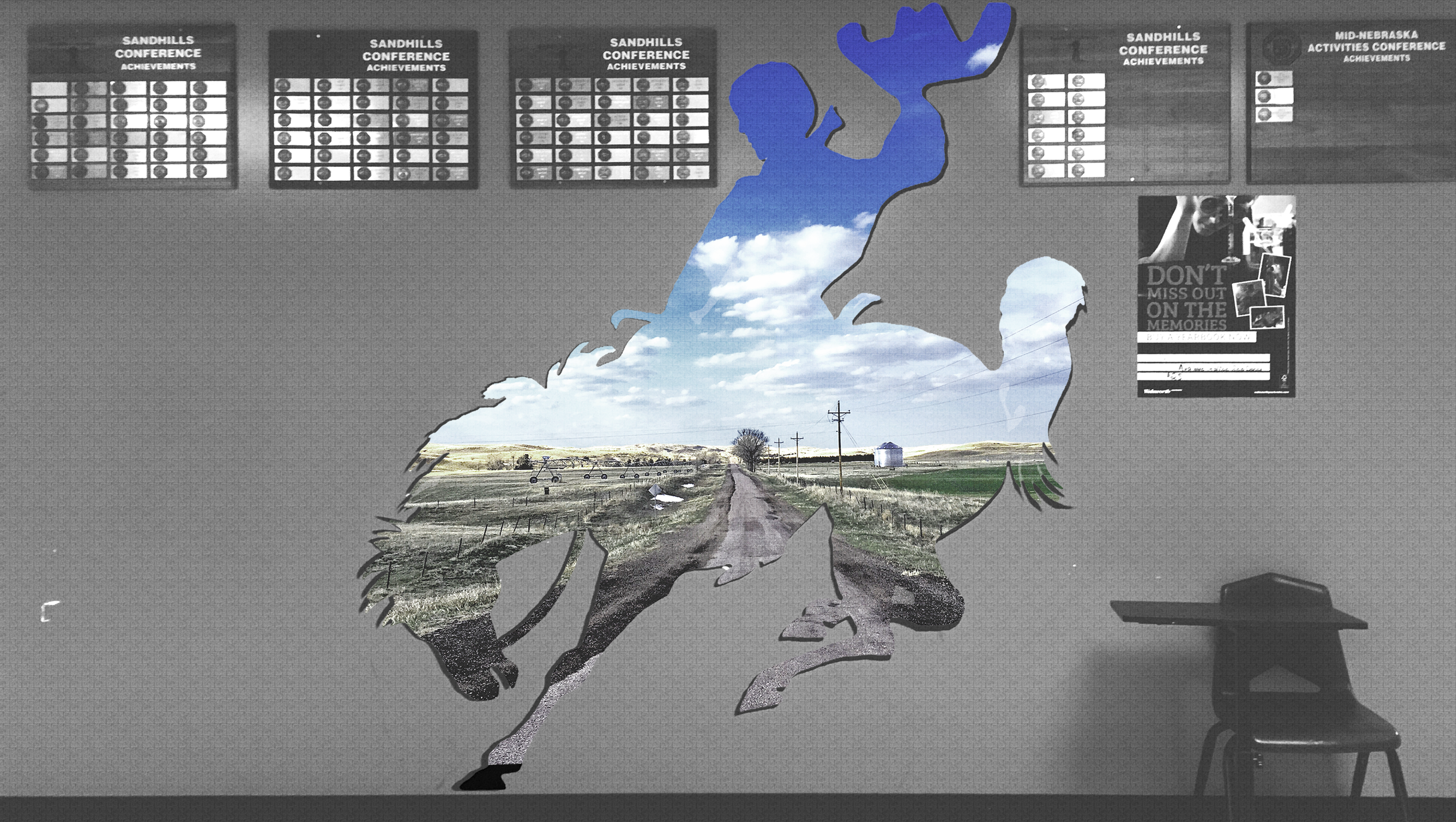

(Photos: Unsplash & Getty Images; Illustration: Ian Hurley/Pacific Standard)

The idea that a community and its school are inextricable—that one is identified and sustained through another—persists in reverse today, as communities all over rural America fight school consolidation, despite the many educational benefits of combining resources. “History, tradition, and culture—those all have some pretty strong meanings in rural areas,” says Jon Habben, former executive director of the Nebraska Rural Community Schools Association. “You don’t just dismiss those lightly because somebody in a big place thinks you’re too small.”

As the graduate of a rural school in central Nebraska, I can personally attest to the power of public schools. Though overwhelmingly white, my class of 73 students included children from all walks of life. Cliques formed outside of class, but during school hours, the rich and the poor necessarily mingled; the farm kids and the town kids collaborated. No question, we lacked many of the resources of larger, more urban schools. I would have jumped at the opportunity to learn French, for example, or to play soccer, which wasn’t offered past elementary school. Some teachers were exceptional, while others were exceptionally indifferent to their profession. Still, I’m often thankful in retrospect for my public-school upbringing: what it lacked in academic resources, it made up for by fostering tolerance and a democratic outlook.

“Education, then,” Mann wrote, “beyond all other devices of human origin, is the great equalizer of the conditions of men—the balance-wheel of the social machinery.”

Kill an afternoon on Cody’s main street and you’ll notice a pattern: a white passenger van shuttling by every hour, past the town park and the community hall, south on Cherry Street at the old filling station, over the decommissioned railroad line, and out toward one of the newest buildings in town—an earthen-stucco straw bale frame with a burgundy tin roof—just off Highway 20. All day long, from the high school to the Circle C Market and back again. Tracee Ford and Stacey Adamson, then both teachers at Cody-Kilgore, came up with the idea for the Circle C, a student-run grocery store in downtown Cody, during a teacher in-service day in 2009.

That afternoon, Ford and Adamson found themselves wondering aloud what it would take to lure more students and families to District 30. Adamson knew several neighbors near her ranch who would have considered sending their children to Cody-Kilgore, but the numbers didn’t reconcile. Why send their kids to Cody, Adamson asked, only to turn around and drive 40 miles back east to Valentine every time they needed groceries? Adamson remembered seeing an article in People magazine about a student-run grocery store in Arthur, Nebraska, an even smaller Sandhills community two hours south. “We just looked at each other and started laughing,” Ford says. “We’ll have to build a grocery store, I guess.”

One call to the Wolf Den Market in Arthur led to another with Nebraska’s Center for Rural Affairs. The deadline for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development grants was just 10 days away, they told Adamson, but they were so excited by the idea that they volunteered to help write the grant proposal. In the meantime, Adamson and Ford recruited a group of interested students who named themselves GRIT (Growing, Revitalizing, Investment, and Teamwork), and together they broadcast their idea throughout the district: a grocery store run by students, utilized by the community, and doubling as an “entrepreneurial training center.”

The project received that last-minute USDA grant and more money from independent groups like the Sherwood Foundation and the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. But grants come with stipulations, and those stipulations muddied an already complex process. To meet the needs of one grant, they had to apply for a second. They had to host fundraisers, solicit donations and in-kind trades, gather letters of support. Locals began to question the whole idea. When the superintendent refused to allow a formal partnership with the school, Ford and Adamson approached the mayor, who signed off immediately. The village would own the building, and a conglomeration of community members and school board members—the GRIT team included—would manage the program.

It took four years from idea to opening, but today, as Janet Shelbourn, executive director of the Circle C, shows me around “Nebraska’s Only Student-Run Straw Bale Supermarket,” a dozen high school students mill about, some crunching numbers in a small office tucked away at the back of the building, some in the adjacent classroom, some unpacking boxes in the walk-in cooler, some out on the floor, moving up and down the short aisles with a mop or a checklist in hand. The wall above the produce reads: IT’S MORE THAN A STORE. IT’S OUR FUTURE! The kids whisper and laugh, but more importantly, they work. They stock the inventory. They run the register. They open and close the store. They even schedule their own shifts during the summer months. It’s a fact the locals sometimes forget.

“The kids handle a lot of it,” Shelbourn says. In addition to the work-based learning, she teaches accounting, marketing, and personal finance, all from within the store—hence the white van, shuttling students to and from the market throughout the school day. She set up the tax system, the accounting systems, the ordering systems, essentially the entire structure for day-to-day operations, but is careful not to micromanage, allowing the students to learn from their mistakes. “I know people get really panicky when we run out of milk or we run out of bread.” But given the age of the students, she says, given cars and crushes and rodeo, the incidents have been astonishingly few and far between. “Sometimes you get some heat back, but I’m just like: ‘You know, we’re an educational facility. I don’t know what to tell you.'”

Just then, the entry bell chimes and two women step inside, one hunched over a walker. Shelbourn shoots up to greet them at the door, but turns back to me to whisper, “This is your shot.” She’s told me about Eva Nollette, how she makes the best cinnamon rolls in town, how she’s legally blind, how students often personally deliver her groceries—as they occasionally do for a number of elderly locals—not just to her house but straight into her fridge. She’s 91 with a white perm, milky eyes, and slow speech, but her memory is sharp as a knife. Not long after GRIT formed, Nollette attended a meeting at the community building, she says. She knew what a school meant to a community and what a grocery store could potentially mean for both.

“Of course, I’m not a native of Cody,” Nollette says with a raised eyebrow and the hint of a smile. Until recently, she lived in the village of Wood Lake, about 60 miles to the east of Cody. “I can remember the years that Wood Lake was a very up-and-coming little community. They got in an argument about their school. The school board wanted to update their records to stay on top of things. The people in the country couldn’t see that, because it was going to cost money for school taxes. They didn’t get the vote, so their school got closed.” Wood Lake went from a town of more than 300 to barely 60 today. “When a school goes down in a community like Wood Lake,” Nolette says, “it’s saying goodbye.”

Adam Lambert, Cody-Kilgore’s latest superintendent, wearing a fitted white shirt and the only skinny tie in Cherry County, reclines behind his desk, sun filtering through the cheap orange curtains behind him. He’s got a swimmer’s build and an accountant’s glasses. A nest of electric cables lies at his feet, and a small American flag hangs overhead. The walls are covered in district maps and school calendars, loose-leaf certificates and messy portraits crayoned by his children. For nearly an hour, he has been unraveling Nebraska’s state aid formula. It sounds simple enough, he tells me: Needs – Resources = Equalization Aid. But in an agriculture-intensive state, the formula quickly begins to crack.

Nebraska relies more on local property taxes to fund its public elementary and secondary schools than almost every other state in the country—52 percent compared to a national average of 36—and it has for many years. Many farmers and ranchers feel saddled with a disproportionate amount of taxation compared to those in more urban or residential areas, especially when land valuations skyrocket, as they did in Nebraska between 2012 and 2016. When property values rise, state aid drops. All of this would seem more appropriate if farm incomes were rising at the same rate, but just the opposite is true. Since the 2015–16 school year, Cody-Kilgore’s annual state aid has dropped by more than $300,000, while farm income has been cut nearly in half.

All of these variables contribute to the perennial debate over state aid and tax inequities in Nebraska, often waged between urban and rural districts. But in the Cody-Kilgore district, specifically, the debate is further complicated by a host of aberrant factors. First, the Samuel R. McKelvie National Forest swallows almost a quarter of the district, more than 65,000 acres, none of which are taxable. Those acres alone, Lambert says, account for nearly $55 million in lost valuation to the district. Second, the Cody-Kilgore district is surrounded on three sides by the Valentine Community Schools district. (The fourth side is the state line.) In the late 1990s, the state required Class 1 schools (K-6 and K-8) to affiliate with a neighboring K-12 district. When landowners were given the choice, nearly all of them chose to affiliate with Valentine where the tax levy was smaller.

If every student in the Valentine district attended a Valentine school, this particular quirk might pose less of an issue. But Nebraska offers an “Enrollment Option,” allowing students to attend public school in districts where they don’t reside. Almost half of Cody-Kilgore’s students opt in, mostly from the Valentine district, often to cut travel time. The state pays each district a fee if it ends up with more students than it started with, what it calls “net option funding,” but it calculates that funding as a resource for the district, not a need, to prevent double counting. “For districts that don’t receive state aid,” Lambert says, not mentioning Valentine Community Schools by name, “that’s just free money. For us, the state deducts that. So we get kicked in the balls even more because we’re accepting state aid.”

With such scant resources, Lambert has to recruit new teachers into the system by touting benefits most other rural schools don’t offer: full family insurance with a low deductible, the four-day school week, the Circle C Market. And now, he’s toying with an idea to provide better and more housing options for teachers. Lambert and his family live in a school-owned home that he is currently renovating by himself. When he’s finished, he’d like to build more: a few homes, maybe a duplex or two, tie it all together with the same type of inter-local agreement he contracted for the market. “Nobody from the outside is going to invest in a town like this,” he says. “It’s going to have to be from the inside out.” And often, that’s the problem.

When Lambert arrived in Cody, he came on strong, the proverbial big-city guy with his fancy ideas—though in fact he’d grown up in several small farm towns himself. He suspended a student on the first day of school. He recommended the cancellation of a teacher’s contract. He bought two new vans and two new cars for the district. He updated the track and the football field. He spearheaded construction of a new weight room. He’s currently mulling over a new bond to further update the facilities. He’s pushing for progress in Cody, whether they’re asking for it or not, and for a time that made people skittish. “They’re nervous about it because they’ve never experienced it,” he says.

As Lambert sees it, the financial straits of public education in Nebraska require scrapping for every dollar. Being the superintendent of Cody-Kilgore, he reminds me, also means being the principal of the high school in Cody, principal of the elementary school in Kilgore, and special-education administrator and curriculum director for the whole district. But more than that, he often substitutes as a bus driver and a custodian too. In the spring and fall, he’s frequently the person mowing the football field and moving the sprinklers. It’s like this for all of the educators in the district. So Lambert has begun exploring with the school board the idea of sending a bus all the way to Valentine, hoping to poach a few students and to increase enrollment at Cody-Kilgore.

“You just survive,” Lambert says. “You do what you have to do.” He’s worried if Cody-Kilgore doesn’t keep looking for aggressive ways to attract more students and teachers, they’ll be staring down the barrel of consolidation—or, more likely, closure. “There’s no one to consolidate with,” he says.

From above, the Sandhills enveloping Cody, Nebraska, mirror the ripples of an empty beach, each shallow trough an irrigated valley or spring-fed lake. Zoom in. Speed east on Highway 20 until you reach Nenzel, population 20, seven and a half miles later. Head south on Route 16F for 24 miles, past the tiny post office, past the vineyard, over the bridge at the Niobrara River, straight through the 116,000-acre Samuel R. McKelvie National Forest, established in 1902 by a proclamation from Teddy Roosevelt, less a forest than a homesteader’s desperation for one. Keep going, past the signs for Steer Creek Campground, until the two-lane narrows to one and the few tight acres of hand-planted pines vanish as quickly as they arrived.

Keep going.

Keep going until you hit the Y at Schoolhouse Lake, surrounded by marsh and cattails, knee-deep in the middle and glistening in the sun, the runway for a squadron of pelicans, herons, cormorants, and mallards. Stay left. Keep going another 10 bumpy miles, cutting through dunes so large you’ll feel suddenly transported to the desert Southwest, to southern Arizona, past Twomile Lake and across the Snake River, until the next fork in the road. Stay left. Curl into Grove Valley and down, finally, toward Boardman Creek. There, 42 miles from Cody, just under an hour’s drive, is the Ravenscroft Red Angus ranch.

“We’re a weird little ranching community,” Shannon Ravenscroft says, so weird—so detached from the rhythms of society—that they literally operate on their own time. “We don’t change our clocks.”

To give me a sense of the miles covered each day by the buses of Cody-Kilgore, Lambert has driven me out to see the Ravenscroft place. The ranch lies in the Valentine Community Schools district—and their tax dollars follow suit—but Shannon and her husband Eric now send their four kids all the way to Cody-Kilgore. Sometimes the kids drive themselves. Other times their parents drop them off at Schoolhouse Lake, where they catch the bus. In either case, the mornings are early, the days are long, and the planning never ends. They text all day. Shannon maintains her teaching certificate—she could homeschool the kids if she chose—but out here, so isolated from the rest of the world, her husband and she take seriously the need for human interaction.

“That’s probably one of the hardest things when you live out in the middle of nowhere,” she says. “I wanted my kids to have experience with other adults. I felt like we needed some kind of socialization.”

Both Eric and Shannon attended high school in Valentine. Back then, boarding out was typical for ranch kids. Rather than make the journey every day, they’d pair up with a family in town. Today, Shannon says, that’s exceedingly rare, though few of the concerns have changed. Miles are miles, and even the most responsible children make mistakes.

“I trust them, and I know they’re good drivers, but you can’t help that you’re tired. Once a year, you hear about a family where a brother and sister were driving and….”

She drops the hypothetical. It’s one Eric and she have had to worry about more than they’d like. Which is why several years ago, they purchased a second home in Cody; or rather, due to Cody’s limited housing options, they purchased a new modular home and planted it one block from the high school. At the time, their oldest daughter, Jaylynn, was beginning her junior year, and the schedule was filling up with extracurriculars.

“It was getting tough, and I was just like, I really need to pray about this,” she says. “Well, then she had a little accident, and I’m like, I think we just need to look for a house. It was just wearing everybody out. Thank God they had four-day school weeks, because on Friday we were, like, done.”

Though Shannon herself now feels busier than ever, constantly traveling between her husband on the ranch and her kids in Cody, the new house has lifted a significant weight from her shoulders. The weeks are still hectic, the texting never ends, but the kids no longer face a long and lonely drive into the hills after a grueling day at school. And it’s not only their own kids who benefit. The Ravenscrofts frequently open their house to other kids from the ranching community who need a place to stay for a quick night before rising early for an FFA conference or a track meet or a choir recital. They’re not the first ranch family to circumvent the travel this way, and they likely won’t be the last.

“It just eases my mind knowing they’re not out late at night on the road,” Shannon says. “The house has taken away a lot of that stress.”

Despite the gargantuan effort necessary to attend, the Ravenscrofts—both children and parents—praise the Cody-Kilgore school system. Their teachers understand the complications of remote living, they say, and the teachers are more than willing to accommodate, whether it be rescheduling a test or meeting with a student outside of regular school hours. The students appreciate the small class sizes, the closeness they feel with their peers, and the opportunity to try out so many different activities, despite having a much narrower range in course offerings and extracurriculars than their peers in larger districts. Overall, they say, a student at Cody-Kilgore cannot succeed in the extracurricular without first succeeding in the classroom.

“So it makes me feel good,” Shannon says, “because you always question whether you made the right choice.”

As we drive back, the miles blur—the prairie, the pines, the sand. Lambert can’t stop thinking about the myriad complications of the district: the rising valuations, the forestland, the unfavorable district lines, the need for more investment in the community, how they’re all knotted up together in a byzantine system he’s constantly trying to navigate. Ideally, he’d like to see the district boundaries redrawn, to carve out a portion of Valentine’s tax base for Cody-Kilgore. He’s not holding his breath. He could appeal to the state, but the vote will return to the people, and the people, he says, are in Valentine.

“You think they’re going to say, ‘Oh, yeah, you can have that land’? No, they’re not.”

So in the meantime, he’s stuck relying on state aid for roughly 45 percent of the budget. “That’s where it gets scary,” he says. “One wrong decision by the legislature—we’re closed.”

Nearly two centuries after Horace Mann introduced the basic principles of the common school, students like those at Cody-Kilgore and others in America’s most far-flung places are again at risk of receiving substandard instruction and training. Established explicitly to balance the scales, the public education system has gradually withdrawn from the farthest reaches—despite vastly improved communication and ease of travel—leaving rural schools to consolidate or compete against each other while their towns continue to wither, their graduates flocking to greater opportunity in the city. Given the circumstances, is brain drain in rural America that difficult to comprehend? When education is no longer prioritized, when mere existence is the goal, is it so baffling that aspiring minds might look elsewhere? When they do, they take their potential with them. Their ideas. Their diversity. What they often leave behind is the status quo.

By the time we return to the highway, we’ve rehashed nearly everything we discussed earlier in his office. By nature, Lambert is an optimist, but there is no denying the challenges facing Cody-Kilgore Unified Schools and other rural districts like it. And though Nebraska is currently one of just six states without a charter-school law, Governor Pete Ricketts has been a staunch school-choice advocate, and the philosophy of cutting expenses at every turn is alive and well in the legislature. Lambert steers with one hand loose on the wheel, eyes trained on Cody as we approach.

“They’re pushing charter schools because the biggest line item on the budget is education. So they’re trying to get rid of it. They’re trying to be the savior, but they don’t realize they’re going to really piss off people.”

We pull off the highway at the Circle C, keep going past the town park and a small electric sign touting the old Cody motto: A TOWN TOO TOUGH TO DIE.

“If they put it on the ballot for the state of Nebraska to vote off property taxes for education,” Lambert says, “there will be a huge storm. What are people going to do when they can’t send their kid to a school?” ❖

Author: Carson Vaughan is a native of Broken Bow, Nebraska. A freelance journalist who writes frequently about the Great Plains, his work has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, the Guardian, Outside, Pacific Standard, Slate, The Atlantic, and other publications. Zoo Nebraska (2019) is his first book.

Editor: Ted Genoways

Researcher: James Gaines

Picture Editor: Ian Hurley

Copy Editor: Leah Angstman

This story is part of the Unseen America project, stories about the struggles and challenges being faced by the misunderstood middle of our nation.