The lights come up all at once during Easter Vigil, a service that takes place the night before Easter morning. It’s the most dramatic moment in the liturgical calendar, and one of the Church’s most ancient offices, a ceremony of light that precedes the mass of the resurrection. The symbolism isn’t difficult to decode: Light is life; darkness, death. But Catholics are keenly attuned to spiritual geography (see: Dante), and so we ask: Where was Jesus in that darkness? Where was he when he was not with us?

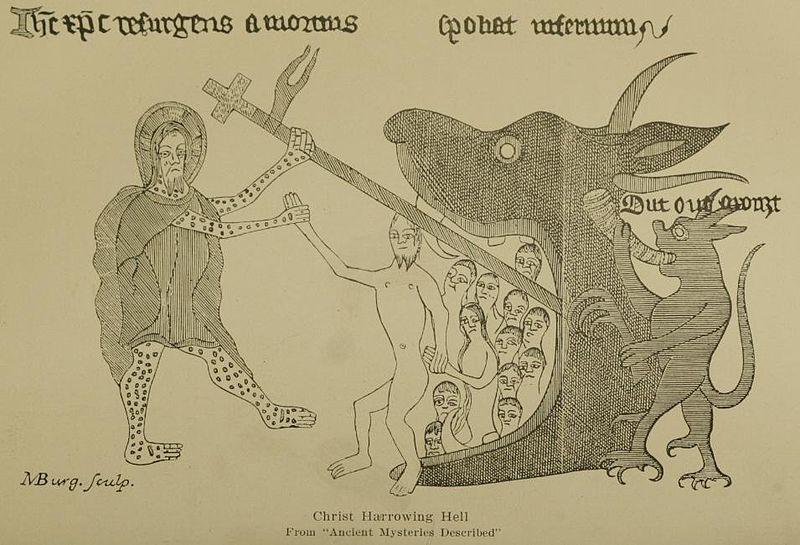

The answer is supplied in the Apostles’ Creed and echoed by many works of art. “He descended into hell,” the profession of faith declares, but as to what Jesus did there, the Apostles remain silent. In England, this journey came to be called “the Harrowing of Hell,” a term coined by Aelfric the Grammarian around the year 1000. According to popular belief, Jesus—left with some free time between Good Friday (his death) and Easter Sunday (his resurrection)—opened the gates of hell to release the righteous who had died before his birth—Adam and Eve, Moses, King David, and so on—and point them to heaven. Visual artists and composers took up the story with gusto. It’s one of the most popular subjects of the Early Modern period.

In one 17th-century engraving of the harrowing, a pockmarked Christ (or maybe he just has freckles?) pries open the literal mouth of hell with his own crucifix. I wasn’t taught this story in church, but so much about the Church I wasn’t taught in church. Most of what I learned about hell was through art.

I don’t know that I ever believed in the devil as a child. My parish preached the “hell is the absence of God” kind of Catholicism; damnation was boring, a cliché. I understood landscapes of terror—I had dreams where my block was populated by ghouls or my world became a river of lava—but I never connected them to the diabolical figure around whom Catholicism would have me organize them. And so while the medieval and Renaissance depictions of hell I’ve encountered (all from Europe, nearly all by Catholic artists) depict an uncanny and gruesome world I recognize—they are not unlike my childhood nightmares—they don’t share my childhood’s religious worldview. The images are at once both strange and familiar.

I found Satan in Italy. It was my first week anywhere in Europe—my Rome-based study abroad program had shipped us off on our arrival to the Apennine Mountains, to Umbria. The high relief sculpture on the façade of Orvieto’s Duomo, a large-scale confectionary of religious architecture without the height of French gothic but all the color of Italian, caught my eye immediately. In it, a fanged and grinning figure wreathed in a crown of snakes clutches his hands before his chest in what looks like an expression of glee. It’s not unlike the gesticulation Wallace, from the British series Wallace and Gromit, makes when he spots a particularly fine specimen of cheese—except this figure’s wrists are manacled. His hips are wrapped in the torso of a great serpent, doubling as some kind of modesty garment. (What will I wear today? Oh I know, a living two-headed dragon.) He stands on bent backs. His feet, too, are chained.

I puzzled at his open-mouthed smile, his fettered limbs: This Satan was, somehow, an embodiment of everything I, an adult non-believer, understood about Catholicism. I had no faith in the details of the Bible—virgin births or vomiting whales—but I recognized suffering and sin and redemption. Staring at this sculpture in Orvieto, though I could not believe in fallen angels or a land of eternal flame, I did believe in this grinning prisoner. I could not put my finger on him, and his resistance to meaning made more sense than anything I had felt in a long time.

The Church officially believes in Satan. It’s on the books—specifically part one, section two, chapter one, article one, paragraph seven of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “It is a great mystery that providence should permit diabolical activity,” the Church teaches, but original sin required “a seductive voice opposed to God,” which tradition recognizes as Satan. Moreover, “the Church, which has the mind of Christ, knows very well that we cannot tamper with the revelation of original sin without undermining the mystery of Christ.” In simpler terms: The existence of Christ requires the existence of original sin, and the existence of original sin requires the existence of Satan.

The Catholic churches of Europe, and especially in Italy, are full of the dead. Skulls sit on velvet pillows crowned by wreaths of artificial flowers. Waxen bodies lie in glass coffins beneath altars. Skeletal fingers—separated in death from the hands to which they belonged—are encased in gold. Churches and museums are full of gruesome or bizarre images: Santo Stefano Rotondo’s panoply of martyrdoms that look like something out of Saw; the Prado’s multiple depictions of the “miraculous lactation” of Saint Bernard, when, yes, the Virgin Mary offered a grown man her breast milk. (In some pictures the Christ child, who she is inevitably always holding, helps direct the stream.)

It was hard to imagine the spare, neoclassical church I grew up in had anything to do with the gilded and marbled spaces (some of them literally classical) I explored during my semester abroad. The former was bloodless, the latter blood drenched. This Church was not illegible, but it was vastly more complicated than the one I was raised in: antiseptic, ahistoric, and apparent. This Catholicism was all body, all past, all mystery.

What is it about a hellscape? Tourists pack the tiny jewel-box room of Orvieto’s Chapel of the Madonna di San Brizio to look up at a mass of gold-leaf and pastel bodies, many of which are contorted in pain. The frescos, begun by Fra Angelico in 1447 and completed by Luca Signorelli in 1499, depict the Apocalypse and Last Judgment. In one panel, three armored and blonde angels look coolly down on a field of bodies, human and demon, like bored security guards. The diabolical figures are easy to point out: they have wings, horns, and technicolor flesh. They grapple with their resistant human charges, gestures that often look sexual if rarely consensual. (One woman’s twisted and tortured pose looks much like Giambologna’s iconic sculpture, Rape of the Sabine Women, and may have inspired it.) Telegraph art critic Alastair Sooke calls the scene “as much porno as it is inferno.” It was the first time I had ever seen such a thing inside a church.

No one really knows what hell, or the devil, looks like—not even the Church. Images of hell often, necessarily, eschew realism. They are also largely non-iconic, with no set repertoire of signs to pull from. (Our modern-day devil—red skin, pointed tail, horned, and humanoid—was codified much later.) It’s the irregularity of these demonic figures in medieval and Renaissance art that I love. Sometimes Satan is a snake, sometimes he is a dragon, sometimes he is a proliferation of lizards all joined up into one Power Rangers-like Megazord body. Sometimes he is a man, a man with wings, a man with horns, a man with wings and horns. Sometimes he looks like a satyr. Sometimes he looks like a chicken. He can be small or large, handsome or ugly, red or blue or even kind of Aryan-looking. He may suffer alongside the damned, rule them, or manage some manner of both. While there was a great deal of exchange—of motifs and color and concept—among artists, there was still no overriding ecclesiastical vision to guide them in their depictions of the devil, demons, and hell. As a result, nearly every medieval or Renaissance painting of the diabolical is a kind of compromise, a proposed solution to a yet-unsolved equation.

Artists, while they were still regularly commissioned to paint the harrowing of hell or carve last judgments, to moralize or conjure fear or inspire obedience, filled up that space with untrammeled and exuberant weirdness. This is not just the weirdness of time or of context—the expressiveness and variety of centuries of European hellscapes created a category of strikingly original and imaginative work, especially when viewed next to hundreds of almost identical annunciations, thousands of near duplicate crucifixions.

Images of the harrowing of hell heighten these contradictions: holy (and so well-regulated) bodies set against unholy (unruly) spaces. One 15th-century Spanish painting shows Christ wearing a cloak so fine it’s translucent, standing astride the crenellated doors of hell. Lurking under a kneeling Adam’s leg, and crushed beneath the doors Jesus had knocked down, lies a wide-mouthed demon gripping a snake whose mouth inches up next to a righteous man’s foot. It curls its tongue upwards and out beyond his many needle-like teeth, as if it can taste something good or bad. Its face, alive with desire and anger, is so much more interesting than Eve’s placid, pious one. She prays on her knees behind her husband.

Behind the haloed figures of the Old Testament struggles a sinner, his tongue hooked by a flame-shooting device operated by a squat half-ape, half-insect and a tall dragon-fish with Don King hair. The striking thing about this painting is not the demons (though I love the variety of forms the artist employs) but the sinner, who continues to be tortured even as Jesus enters the scene. If Christ is powerful enough to throw open Satan’s doors, why not end hell altogether? But this is the harrowing of hell story’s central point: What matters isn’t that Jesus went to hell, it’s that he left it. And that he left it intact.

On one of my first days in this complicated place, I found a kind of key on the side of a church: a manacled figure, grinning and strange. My first Satan, outside the Orvieto Duomo—the first I really noticed and admired and, yes, felt affection for—coiled and curled with snakes for crowns and serpents for clothes. He was so very much himself, real and bizarre at the same time. This devil thrived on and even seemed to celebrate contradiction—both animated and restrained, joyous and tormented, beautiful and grotesque, transgressive and disciplined. This work—and all the works that followed—showed me space in the Catholic universe where believers explicitly made it up as they went along, and where I, a non-believing Catholic, might make something new. Not belief, exactly, but understanding. It was an entrance back into the light, right through hell’s mouth.