The Trump era has, so far, been a violent one. Since Donald Trump announced his presidential campaign in the summer of 2015, assaults of pro-Trump and anti-Trump protesters, as well as journalists covering the 2016 campaign, have made headlines. Meanwhile, Federal Bureau of Investigation data has found that hate crimes against Muslims increased by 67 percent in 2015, while the Council on American-Islamic Relations reports that those same crimes increased by 44 percent in 2016. In response, leftist activists and minority groups have turned to a form of activism that some might not typically expect from liberals: to counter and prevent violence, they are heading to the gym to learn self-defense.

The list of these new self-defense initiatives is long: Among other efforts, Minneapolis’ Oh Hell No bike rides patrol neighborhoods to prevent sexual assaults and harassment; Chicago resident Zaineb Abdulla hosts self-defense seminars for Muslim women; the company Trigger Happy Firearms Instruction holds firearms lessons for women in several cities across the United States with the ultimate aim of teaching a million to shoot. And in April, the Chicago-based group Haymaker Collective formed—and is currently raising funds—to open a sliding-scale fee gym where anyone (except politicians and police officers, who the collective does not trust to keep them safe) can take self-defense classes and work out regardless of income, gender, sexuality, race, ability, or religion. Their end goal is to help people “learn the skills they need to stay safe in Trump’s America,” according to their Indiegogo campaign.

In American culture, self-defense is usually associated with conservative policies that aim to preserve (and/or broadly interpret) the Fourth Amendment and national security. Consider Stand Your Ground laws, which allow residents of some states to use lethal force in self-defense against intruders without first attempting to flee; or the language of protection that Trump and members of his administration have used to promote the administration’s travel ban on several Muslim-majority countries. Nevertheless, leftists have long prepared for violent, politically divided times too—albeit with a very different approach. While conservatives have often organized measures that ostensibly help keep everyone safe but ultimately serve to preserve a status quo, leftists have historically practiced and taught self-defense techniques to empower marginalized communities.

Like several other Trump-era self-defense initiatives, Haymaker says it wants to provide a space for vulnerable people in Trump’s America to feel more autonomous. The goal of the activist collective, some of whom identify as anarchist and antifascist and others who do not, is to empower individuals to protect themselves and their communities—with the help of rowing machines, treadmills, and punching bags.

Five members of Haymaker—who requested Pacific Standard publish only their first names to protect their safety—wrote in a group statement that they began crowdfunding their gym because they didn’t trust justice institutions to protect them. Instead, the members—Sonu, Joie, Naila, Amy, and Oliver—say they “[chose] to learn how to defend ourselves in the moment” by establishing Haymaker. The collective is young—all 10 members are between the ages of 21 and 37—and diverse: All are members of minority groups in the U.S.

On its website, the Haymaker Collective states that their group was, in part, inspired by Pacifico Di Consiglio, a 17-year-old Jewish boy from Rome who organized an anti-fascist boxing gym after Benito Mussolini passed several anti-Semitic laws in 1938. Di Consiglio organized groups of Jewish boys who fought fascists in the Jewish ghetto; he once managed to escape an SS vehicle by punching out a guard as he was driven toward Fossoli di Carpi, a deportation camp.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

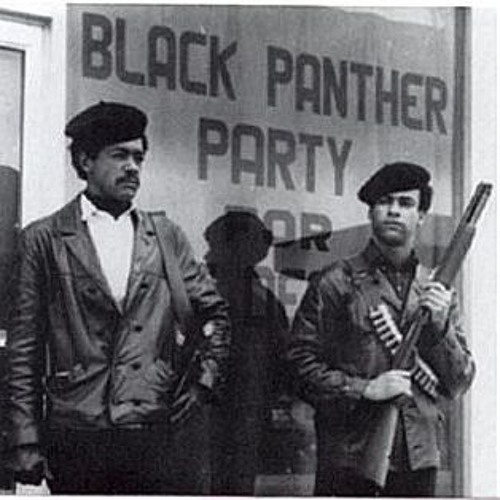

But Di Consiglio and his crew are hardly anomalies in the history of leftist activism—minorities and equal-rights activists have practiced self-defense during times of significant political unrest for over a century. 1886’s Haymarket Affair, and martial arts training within the United Kingdom suffragist movement, were early examples of physical leftist agitation. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s civil rights movement, black activists were routinely attacked during non-violent demonstrations and race riots that occurred in New York, Detroit, Newark, and Los Angeles, among other cities. And while non-violence was indeed a prominent tactic in the civil rights era, practiced and encouraged by Martin Luther King Jr., the militant defense organization the Black Panther Party famously carried weapons openly to protect themselves. But they weren’t the only ones with guns.

In his book This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible, professor and former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee field secretary Charles E. Cobb Jr. explains that it was also common for black people in the South to own guns in the 1950s and ’60s. Black people at this time responded “to terrorism the way anybody else would,” Cobb told NPR in 2014. Like all people and movements, black activists of the era had “contradictions,” he said, but were ultimately “ordinary people” who did what they felt was necessary to stay safe—which sometimes meant owning a gun.

Not long after, the women’s liberation movement both passively and aggressively defended themselves. In the 1960s through ’80s, violence against women was commonplace, at home and in pop culture: A 1975 study on domestic violence in the U.S. found that up to 16 percent of families in the U.S. were involved with domestic violence each year, demonstrating that partner abuse against women was more than a one-off issue. At this time, Ms. magazine encouraged readers to send in sexist ads for their “No Comment” section: One, for a bowling alley in the ’70s, read: “Have Some Fun. Beat Your Wife Tonight.” Though the women’s liberation movement began with avoidance measures, such as avoiding nightlife and traveling in groups, physical self-defense became more popular as the feminist movement progressed.

Around the country in the 1970s and ’80s, women’s rights activists held self-defense trainings in martial arts studios and on college campuses, providing evidence of a shift toward aggressive approaches to violence. Founded in 1989, Rape Aggression Defense, a self-defense program that is still in existence today, trained women to physically ward off would-be rapists.

LGBTQ people, too, made widespread use of self-defense practices. In the early 1970s several formed a self-defense organization called the Pink Panthers Patrol nodding to the Black Panther Party. The Pink Panthers kept watch in New York City’s West Village neighborhood on weekend evenings in order to prevent violent attacks against gay people during an era when anti-gay hate crimes had only just begun to be monitored and recognized by the government. The patrol group still exists today, now called the Pink Panther Movement.

Today, black rights activists, women, and LGBTQ people have reprised self-defense, even arms training. In August of 2015, the Black Women’s Defense League was founded in Texas to offer self-defense and arms training for “abused, underserved black women and marginalized genders.” This year, The Trigger Warning Queer and Trans Gun Club formed to “educate and organize queer and trans people for self-defense,” according to the group’s Facebook page. In the Trump era, self-defense organizations have particularly marketed their services to Muslim women: As reports of attacks against the Muslim community mount, self-defense practitioners in Manhattan, Chicago, and Antioch, Tennessee, are offering self-defense courses specifically for Muslim women.

Today’s physical leftist resistance adheres to many of the philosophies and tactics employed by their predecessors from the 19th century and later, focusing on grassroots self-defense measures by and for the people who are most at risk. In periods of tense political and social tension, communities and activists still fighting for equal rights have sought not only to build physical, but also existential, strength, which comes from joining together in times when they feel threatened.