This story was produced in collaboration with APM Reports.

In many parts of the country, it’s becoming easier than ever for former felons to vote. A growing number of states have loosened restrictions, such as allowing people to cast ballots while still on parole or probation. But there is one region that still has a penchant for purging felons from the rolls: the South.

An APM Reports/Pacific Standard analysis of federal data shows that, in the past decade, the number of registered voters removed from the rolls across the South due to a conviction has nearly doubled. That trend comes at a time when overall crime rates have been declining.

States with the largest voting-aged, African-American populations tend to have some of the strictest laws. And that’s created a disproportionate impact on minority voters. In fact, the laws were initially designed 150 years ago to suppress African-American political influence.

Bans on voting by felons arose in the years following the Civil War, after adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed equal legal protections for all men. African Americans, having gained the right to vote and run for office, were a growing political force in former Confederate states, and, with Reconstruction ending, southern states were scrambling to draft new constitutions. Lawmakers couldn’t legally ban African-American participation. So they found ways to tamp down African-American voting by passing laws that looked race-neutral on their face but were intended to discourage black voters. Between 1890 and 1906, every state across the South adopted bans on felons voting. At the same time, prisons swelled with former slaves and poor whites who were arrested during a crackdown on petty offenses, like vagrancy, under new, so-called Black Codes.

The felon-voting bans were passed ostensibly to ensure election integrity. But the true intent was made clear enough by some delegates intent on suppressing African-American influence. Among them was Solomon Saladin “S.S.” Calhoon, who told fellow delegates at the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890: “We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this will answer.”

More than a century later, many of the legal barriers to voting enacted during the Jim Crow era have been overturned. But the bans on felon voting have survived and are being employed most fervently in the region where they were most widely embraced post-slavery.

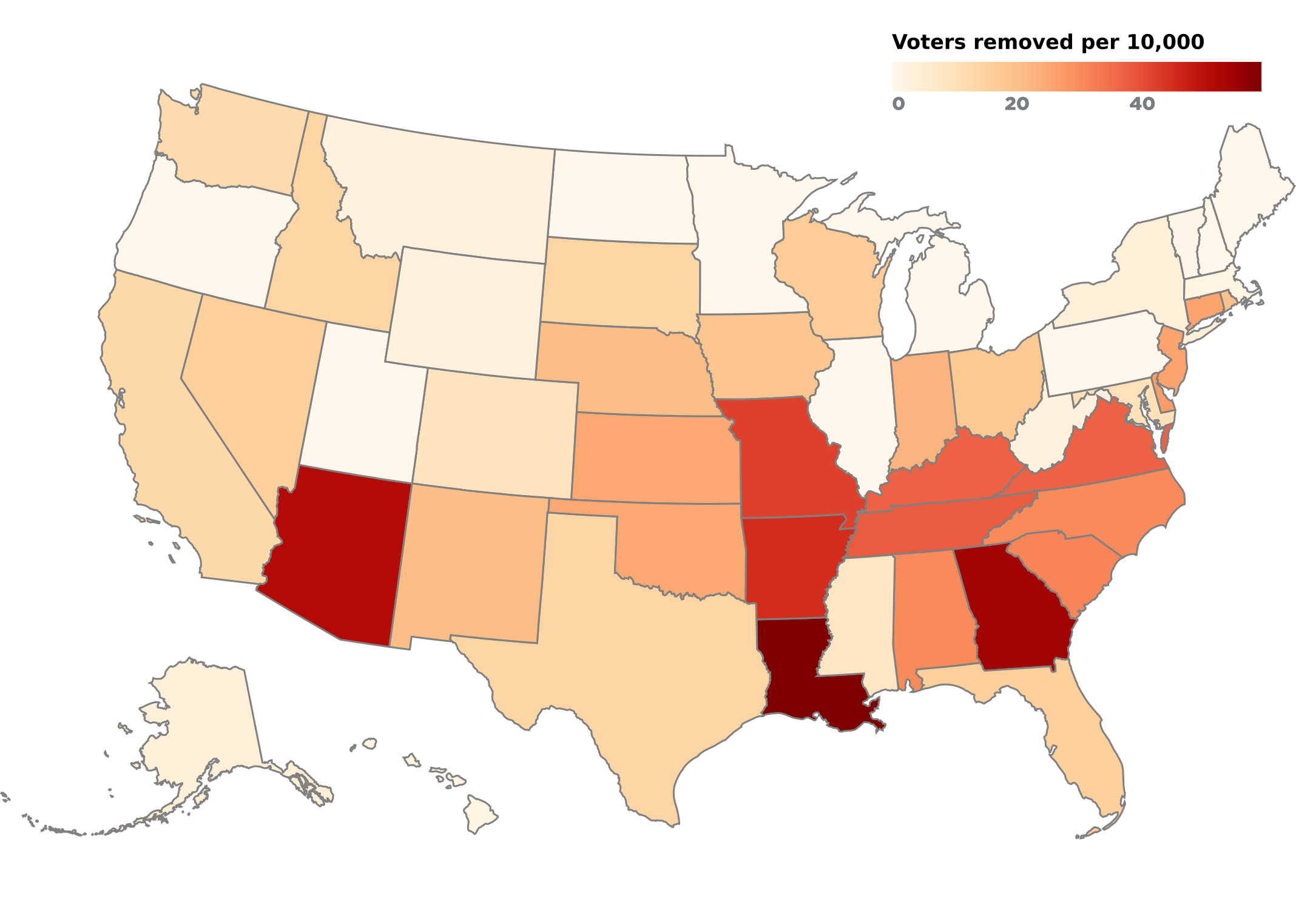

Between 2008 and 2016, nearly 900,000 registered voters were stricken from voting lists in states south of the Mason-Dixon Line, according to the APM Reports/Pacific Standard analysis of data compiled by the United States Elections Assistance Commission. In all, more registered voters were cut in those 14 states than the rest of the country combined.

(Map: U.S. Election Assistance Commission Election Administration and Voting Survey; Geoff Hing/APM Reports)

On November 6th, Florida voters will decide whether to lift that state’s lifetime ban on felon voting. Advocates say that restoring voting rights bolsters civic engagement, which is good for communities. And they question why people should be punished if they’ve otherwise paid their debt to society. While voting rights advocates hope that Florida will set an example in breaking from the past, in other states, like Georgia, there’s reluctance to start a debate.

“I don’t know if Georgia is ready for that. We are in the Deep South,” says Doug Ammar, who heads up the Atlanta-based legal aid non-profit, the Georgia Justice Project. There’s tension in pushing for changes because lawmakers might end up making it harder for people to vote, which has happened in other states.

In Georgia, officials have been under scrutiny for a string of alleged voter suppression tactics, from polling-place closures and voter purges to registration obstacles. A recent APM Reports investigation found that that state had purged an estimated 107,000 people in 2017 largely for not voting in prior elections.

At the same time, Georgia has kicked more people off the voter list over a criminal offense (nearly 147,000) than any other state in the country during the past decade, federal data shows. It’s a process with layers of bureaucracy that begins with the corrections department periodically sharing lists with election officials of people who ought to be purged.

African Americans have been disproportionally affected by the purges: Since 2016, they’ve accounted for 52 percent of felony removals, according to an analysis of records obtained from the Georgia secretary of state’s office. That’s nearly twice their share of the state’s voting-age population, census data shows. Meanwhile, whites make up 36 percent of removals, almost half their share of the voting-age population in that state.

Courts have been unmoved by the disparities, repeatedly upholding the laws dating back to 1974, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Richardson v. Ramirez that felony disenfranchisement does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

Despite the legal affirmation, state legislatures have actively loosened restrictions for years. In the past decade alone, at least 11 states have made it easier for people with a past conviction to vote, according to research by the National Conference of State Legislatures. In most places today, people can have their rights restored after they’re released from prison, probation, or parole. In two states—Vermont and Maine—people can still cast ballots while they’re incarcerated.

But lifetime bans remain in Florida, Virginia, Iowa, and Kentucky. And, across the South, the impact of those laws adopted a century ago continues to afflict voters, even those who’ve put their criminal pasts behind them.

In Georgia, for example, Kerry Bird realized that shedding his criminal record wasn’t going to be so easy as he stood before the State Board of Elections, snarled in a voter fraud investigation in 2014. Four members of the board, headed by Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican who’s been criticized for zealously investigating voter fraud, were debating whether to recommend that the state’s attorney general investigate the six times that Bird voted while on probation.

People in the same situation have faced prison sentences. Earlier this year, Crystal Mason was sentenced to five years in prison for casting a ballot in Texas while under court supervision. In North Carolina, a dozen people were recently charged with illegally voting in the 2016 presidential election under similar circumstances. Each faced up to two years in prison, but some have since pleaded guilty and were sentenced to probation.

Bird, now 63, is a farmer who tends cotton in Metter, a rural town in Georgia about an hour northwest of Savannah. He’s married to a teacher and has children. But in 1989, he was convicted of theft, which he blames on a drug addiction that he broke decades ago. By 2004, his probation had officially ended but he began voting in elections before his case was closed.

A decade after he thought he’d put his criminal past behind him, it reared up again, and the state began investigating him. “It was a scary thing,” he says. “I was thinking that all of this should have never happened.”

In each of the six elections that Bird voted in, poll workers never hinted at a problem with his status. But it turned out that, even though his probation officer had released him, Bird was still technically under court supervision. This is not an uncommon scenario in Georgia. The state’s probation population is the highest per-capita in the nation, which experts say is, in part, the result of backloaded sentences that are a combination of a lenient prison time and extended supervision. The state is trying to get a handle on a system in which roughly 61,000 people have been under supervision for a decade or longer, according to a 2016 report by the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform.

Ammar’s organization, which does legal aid for hundreds of felons reintegrating into society, writes letters to judges and probation officers requesting documents for clients who hit voter registration barriers. The system is fraught with miscommunication, he says, and a lot of people don’t even realize they’re eligible.

Georgia’s state elections board examines dozens of voter fraud investigations like the one that flagged Bird each year. After hearing the facts in Bird’s case, election board members concluded that too much time had passed. Ultimately, they dropped the case.

The investigation rattled Bird, but it hasn’t kept him from participating in politics. He’s paying close attention to the governor’s race in which Kemp is running against Democrat Stacey Abrams. Bird’s been through enough, from military service to being banned from voting, that he thinks it’s vitally important to stay involved.

But he warns others who have been convicted of felonies to double-check whether they’re eligible to vote before going to cast a ballot.

“You don’t want to try to do the right thing, and you get more trouble for it,” he says.

Geoff Hing with APM Reports and Johnny Kauffman with WABE, the public radio station in Atlanta, contributed to this story, which was produced in collaboration with APM Reports, a division of American Public Media.