At 16 years old, I interviewed Ian MacKaye.

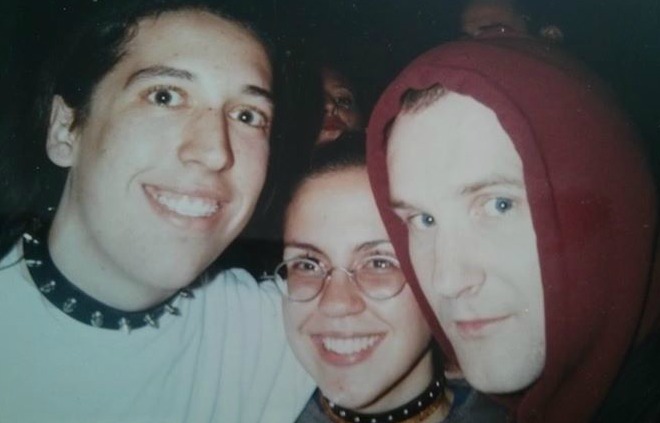

Standing in a weird sort-of tiki hut behind a rock club in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, on April 2, 1996, I stubbed out an unfiltered Camel and asked strange, sometimes stupid questions to this punk rock iconoclast, the lead singer of post-hardcore band Fugazi.

I was talking to the man who founded enormously influential Dischord Records, who created (and later disbanded) hardcore punk legends Minor Threat, who then somehow brought out another great band in Fugazi. With a hooded sweatshirt and combat boots, a dedication to veganism and an élan for eschewing drugs and alcohol, this guy could count himself among the godfathers of American punk rock. And all I wanted to know is whether he might equate the health risks of caramel with the supposed evils of eating meat.

I’m embarrassed even now, recalling that moment. To make matters worse, I’d been pronouncing his last name incorrectly. (You try it.)

With little regret, I’ve since misplaced the cassette tape of that interview. Likewise, most of the magazine copies that contained the ill-fated Q&A are also long gone. But I lost another artifact from that night: At a rock club called the Edge in South Florida nearly 20 years ago, I slipped a second 90-minute cassette into my recorder, which helped burn into my brain a memory—or so I thought—of what I have always said is the greatest concert of my life.

The evening had a lot going for it: I was attending the concert with my co-editor, a woman I sort of thought I loved. (Recall: I was 16.) After the interview, we finally got past security to find the place packed. With luck, though, we found an amazing spot on the mezzanine. I pressed the red button on my recorder. Surveying the venue, I thought about my life at that moment. Months earlier, MacKaye’s record label paid to advertise in my silly music magazine. Just moments before, the founder and singer took the time to do a sit-down interview. Pretty soon, high school would be over. Who knows what would happen? The lights dimmed.

In the weeks and months following that show, I listened to the tape over and over. Remembering the utter chaos of a mosh pit, the way I nervously smoked cigarettes, even the damp men’s room, I invested in that crude field recording a lot of meaning.

Memory is a strange thing, and getting older is tough. Our brains degrade and the sharpness of what we’ve stored dulls. In fact, according to a recent study in the Journal of Neuroscience, every time you access a cherished memory, your ability to faithfully recall the so-called original gets weaker over time. So if there’s some moment you want to cherish, such as a Fugazi concert in 1996, your desire to actually do that cherishing is fundamentally doomed. Unless, that is, you have a tape.

The posters from all the shows I hung up on my wall when I was growing up? Those were all thrown away when I re-painted the family house one summer. All the t-shirts I bought at various concerts? Donated when they began to fray. The seven-inch records I had people sign? Left in a sublet in Brooklyn. I even managed to misplace all three giant cases of CDs I’d been toting around for a decade—losing about a thousand albums, some of them in theory irreplaceable. (Anyone have a signed copy of that Screeching Weasel/Born Against single?)

How hard could it be to hold onto a tape?

Somewhere amid all that time spent rolling around my memories, I grew up. I found another woman, whom I loved and eventually married. I moved on from a self-made music magazine, eventually working for a time at Rolling Stone. I lived in New York and Istanbul and Beirut and Los Angeles. I even had a little girl of my own, five years old, whom I hope one day to introduce to the strange beauty of a band like Fugazi.

All along, through all the airplanes and hotels, whenever my mind drifted off, it would inevitably return to that old memory from the show. And that cassette.

In the weeks and months following that show, I listened to the tape over and over. Remembering the utter chaos of a mosh pit, the way I nervously smoked cigarettes, even the damp men’s room, I invested in that crude field recording a lot of meaning. (There are nights when things go right—and you cling to them as evidence that you can and should go on.)

So: According to science, we forget stuff, or we can’t remember it right, or we are doomed to degrade the memories we want to cherish most. It turns out it’s just as easy, if not easier, to misplace a physical object. And it’s maddening.

Over the years, when I was home from whatever weird adventure had taken me to Indonesia or Alaska or wherever, I tried desperately to recapture what I’d lost. Rooting through boxes or pestering my mom for intel, I’d wonder: Did my copy of the cassette break? Did I give it away? Did it even come with me when I left Miami? Or was there, painfully, some moment when I thought I didn’t want it anymore?

Flash-forward nearly 20 years later, to the spring of 2014. My first book was coming out and I was in a nostalgic mood. In one obsessive Google search, I came across Dischord Records’ massive database of Fugazi shows, many of them apparently available for download. I browsed until I found the one dated April 2, 1996.

It was the greatest rock show I’d ever seen.

In my memory, there was this moment when the power went out. The lights dimmed and the guitars went silent, but drummer Brendan Canty kept going, pounding out the beat. It was, to me, one of the most remarkable moments in rock history—at least my rock history. I’d told and re-told it: to my wife, to friends, at parties, to fellow editors at Rolling Stone. How, for 10 minutes (or was it five? Or just 30 seconds?) the drummer played on, while we all stood there, transfixed.

So I’m stumbling around Google. I find the show and I start downloading.

My wife walks into the bedroom soon after I hit play. She knows something is up. I have the music blasting. It’s “Sieve-Fisted Find,” a driving, haunting song I still love, with lyrics like, “Here comes another problem, wrapped up in a solution.” But it’s not the studio recording. It’s too ragged, too raw, to be a studio recording.

The lights dimmed and the guitars went silent, but drummer Brendan Canty kept going, pounding out the beat. It was, to me, one of the most remarkable moments in rock history—at least my rock history.

“Is it that show?” Kelly says. “The one you always talk about?”

Our bedroom feels like a séance. As I listen, I tag on Facebook the one guy I’m sure I gave a copy of the tape to. Man, I’m listening to that show from 1996, the one where the power went out. He responds, saying he too remembers the show—the packed house at the Edge, the glee that they were playing so many of their hits, the skinheads Ian MacKaye asked to leave. But the power outage, he writes, I don’t know.

I listen. The recording is amazing. I’ve forgotten how perfectly they performed “Promises.” But by the time I make it to minute 30, I get a bad feeling. Nowhere is there an inspiring stretch of silence; nowhere is there a moment when the drummer keeps playing. But I can remember it so well. I’m sure it happened. Aren’t I?

At a certain point, whether the memories are physical or mental, the things you once cherished are gone, replaced by newer things you think you claim to now care more about. Occasionally, old flickers or accidents can remind you that perhaps some things are better forgotten.

Music is perhaps different, in the way it endures or doesn’t, in the way an old song once loved can become a song loved anew, especially if you have children. But in many cases, who we listened to as kids doesn’t always retain its ostensible valuable. To be honest, I rarely listen to Fugazi anymore; certainly not as much as I did when I was 16.

Back at my house, the recording plays on. There’s no power outage, and no silence, at least that I can hear. But damn do they sound good.

Just like that, the band is thanking the crowd. “Peace,” Ian MacKaye says in farewell. It’s over. There’s no drum solo. There’s no power outage. I begin to wonder if the silence ever happened.

So here I am, face-to-face with a kind of truth. I say it to myself, like some sort of chant: From 1987 to 2002, Fugazi played more than a thousand shows, all of them for five bucks. The one I saw is the one I’ll never forget.

Why does it matter so much to me? Isn’t the idea that it happened enough? After all, I’ve told the story enough that it’s taken on its own kind of life. (Plus, I reason with a flicker of hope, if this recording went through the soundboard, it was probably on a deck that was using power itself. So when the juice cuts, so would the recording, right?)

It’s all so confusing. Maybe this is what we can say: Sometimes the fragile things we hold in our minds are more valuable than any physical manifestation, more important than the truth, and more real than anything we can dig up on the Internet.

I hit play again. If nothing else, there’s something incredibly pleasant—incandescent, marvelous, delicious, pointless, untrue, maybe—to have been gifted this swirl of contrasting possibilities. Fugazi was incredible live.

Lead photo by linesonpaper/Flickr.