The nearly 53,000 people in Georgia whose voter registrations have been frozen, or are “pending,” under a controversial new election administration scheme mostly live in the urban parts of the state. About 98 percent of the names on that list hail from just 10 counties, all of them connected to Georgia’s most urban areas:

- Bibb County, where the city of Macon is. (933)

- Dougherty County, where the city of Albany is. (1,287)

- Richmond County, where the city of Augusta is. (1,557)

- Chatham County, where the city of Savannah is. (2,827)

- Muscogee County, where the city of Columbus is. (3,076)

The other five counties where the bulk of the voter registrations are frozen are in Atlanta’s metro suburbs, and four of those have the highest total number of pending voter registrations in the state. In all but two of the 10 counties, the percentage of pending voter registrations that belong to African Americans is larger than the black share of the population in those counties.

Gwinnett County, in Atlanta’s northeast suburbs, only has a black population of 25.4 percent, and yet 35.4 percent of the voter registrations challenged come from African Americans (Gwinnett also has a population that is 20 percent Latino, which is roughly the same percentage of Latino voter registrations that have been flagged). Fulton County has more voter registrations placed on hold by far than any other county—20,768 compared to DeKalb County, which is No. 2 with 10,541. Roughly 44 percent of Fulton is black, but 75 percent of the voter registrations on hold come from African Americans.

Civil rights organizations are suing Georgia and its Secretary of State Brian Kemp to stop this program. Kemp is presiding over the state’s elections while running as the Republican nominee for governor. His opponent, the Democratic candidate Stacey Abrams, is running to be the first African-American woman governor of Georgia.

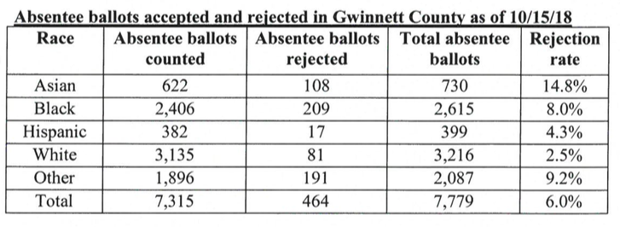

Gwinnett County is one place worth keeping an eye on in this race as it is the locus for several questionable election policies that sound a lot like voter suppression. It not only has the third highest number of suspended voter registrations among all counties, it also has the highest rate of rejected absentee ballots in the state. In fact, Gwinnett County alone is responsible for 40 percent of the tally of rejected absentee ballots across Georgia. And just as with the frozen voter registrations, it’s voters of color who are disproportionately affected—8 percent of African Americans’ absentee ballots and nearly 15 percent of Asian Americans’ absentee ballots have been rejected compared to just 2.5 percent of whites’ absentee ballots that have been returned.

It is not clear why so many ballots are being rejected in Gwinnett County, but the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law sent a notice letter to Gwinnett officials last week requesting the records kept on this matter to find out.

Gwinnett, the second most populous county in the state, is a political battleground in Georgia that Republicans are desperately trying to hold on to in the face of swiftly changing demographics. The county’s white population decreased from two-thirds white to 41 percent white between 2000 and 2013. George W. Bush won Gwinnett in 2000 with 63.62 percent of the county’s votes, and Republicans have held power there ever since. Or at least that was true until 2016, when Hillary Clinton won over Donald Trump, 51 percent to 45 percent. Democrats won several other state legislative and county seats representing Gwinnett from Republicans during that 2016 election as well.

And the population shifts are surfacing racism in myriad ways. Gwinnett County commissioner Tommy Hunter, who is white, was recently reprimanded by the ethics board for calling United States House of Representatives member and civil rights leader John Lewis a “racist pig” on Martin Luther King Day last year. More consequently, after Republican incumbents barely won the state House District 105 in 2012 and 2014, a once solid-red district that encompasses Gwinnett County, GOP lawmakers redrew the district’s boundaries by subtracting black voters and spreading them across neighboring districts, which effectively diluted their voting strength and protected the white Republican incumbent Joyce Chandler.

Last year, civil rights organizations sued the state, with Georgia Secretary of State and Republican gubernatorial candidate Kemp as the named defendant, over this redistricting move, arguing that it constituted an unlawful racial gerrymander, in violation of the Voting Rights Act. A judge who ruled earlier this year on the case said she found that the evidence for racial gerrymandering is “compelling.” The litigation is still pending.

It should be noted that this possible case of gerrymandering is the product of a third wave of redistricting conducted by Republicans in Georgia since 2010. The first two, drawn in 2011 and 2012, had to be pre-cleared—reviewed and approved—by the U.S. Department of Justice because Georgia was, at the time, subjected to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Section 5 was created to prevent states like Georgia, that have long histories of discrimination against voters of color, from continuing to pass racially discriminatory election policies. But the U.S. Supreme Court struck Section 5 from the Voting Right Act in 2013, which gave Georgia free reign to pass any kind of election policy it wanted to without federal review. And that is exactly what Georgia lawmakers did, by serving up yet another round of redistricting in 2015 that included the questionable redrawing of District 105 in Gwinnett County.

The muting of Section 5 in the Voting Rights Act also allowed Georgia to institute the controversial “exact-match” voter registration into law, after earlier versions of it were challenged and rejected on voting rights violation grounds. Had Section 5 still been in place, there would have been federal checks and balances to ensure that Georgia’s new election laws and policies would not discriminate, without the need for costly lawsuits to make these determinations. Between the frozen voter registrations, the rejected absentee ballots, and the gerrymandering, it’s clear which voters are being targeted, and it’s not the ones who will likely vote for Kemp in November.

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.