Comics scholar Hillary Chute has a curious origin story. Once an unassuming graduate student in New Jersey, her life changed forever when Art Spiegelman saw an obscure Web piece she had written and invited her to a party. Soon thereafter he asked her to collaborate on MetaMaus, the companion book to his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel. It turned out to be the first of many unconventional working relationships Chute has enjoyed with practicing cartoonists like Alison Bechdel.

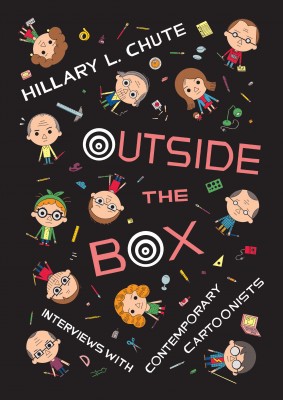

Since 2005, the year she met Spiegelman, Chute has interviewed cartoonists for outlets like the Village Voice and the Believer in parallel with her academic work. Her new book, Outside the Box (University of Chicago Press, 2014), collects 11 of those conversations. She also just co-edited a special comics-centric issue of Critical Inquiry (“academe’s most prestigious theory journal,” per the New York Times). It is probably the only academic publication to date that features cover art by R. Crumb.

Of course, comics haven’t always been the objects of “serious” criticism. Not so long ago, Maus was one of the few graphic texts considered respectable enough to teach in higher-ed classrooms. Over the last 10 years, the field of comics studies has been expanding very, very rapidly, with English departments embracing everything from mass-produced superhero fare to the groundbreaking comics journalism of Joe Sacco. At the same time, cartooning as a practice has become more institutionalized. Underground heroes like Ivan Brunetti have day jobs as art department faculty members, and there is at least one dedicated degree-granting facility, The Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont.

In May 2012, Chute assembled 17 of the world’s most famous cartoonists for a conference, “Comics: Philosophy and Practice,” at the University of Chicago, where she works as an English professor. At the time, I was trying to contact many of the same cartoonists for a writing project. Having all but resorted to carrier pigeons and smoke signals to reach this reclusive bunch, I came to see Chute as a sort of superhero. Certainly, she’s one of the only people in the world who could have gathered such an illustrious group.

But as we all know, with great power comes great responsibility. Through that conference, and through her beautiful new book, Chute has emerged as the foremost comics scholar of our time, as well as one of the few female voices in the world of pop criticism. (As of this writing, The Comics Journal, the central repository for literary comics analysis on the Web, has more than 30 interviews, reviews, and columns on its homepage—all of which were written by men.) As the form begins to draw more interest and scrutiny from all sides, a certain narrative about the history and value of comics is settling into place. While she seems deeply reluctant to acknowledge it, part of Chute’s job is to select who will be the protagonists. I recently spoke with her about this fascinating work.

You were still in graduate school when you first started working on MetaMaus. How did that collaboration (with Art Spiegelman) come about?

He was actually one of the first cartoonists that I met. When I was in grad school, I had none of this access that I have now to the people that I write about. It wouldn’t have ever occurred to me to track down Art Spiegelman and talk to him. But I wrote a piece about Maus for an online comics criticism magazine that was started by one of my former students. My email was attached to the piece, and Art Spiegelman invited me to a cocktail party at his house. It was like winning the lottery for me. I had been spending years and years working on this dissertation, and then suddenly I’m being invited to his house.

We realized that we were both intensely interested in comics form. One of the things that he said that really struck me was that in a lot of academic writing about Maus, although he liked a lot of it, one could read the essay and potentially think it was written about a novel. So somehow the whole idiom of comics was missing from academic analysis. I was intensely interested in comics form, so we got along very well. He asked me pretty shortly after he and I started having conversations about comics to work with him on MetaMaus.

I had already done a lot of thinking about Maus, and I think that’s part of why he and I hit it off. My very first academic article, which is on Maus, had already been accepted for publication. So that was kind of nice timing for me, because the anxiety of influence wasn’t too heavy. I had already done work on my own and I was bringing that to the table as opposed to just being guided by the artist.

I know your relationships with Spiegelman and other cartoonists have been important to your work. And I also know from my own experience that many cartoonists are really difficult to reach. Do you think that it’s important for academics that work on comics to engage with people who are practicing in the industry like you have? And is it even realistic to think that they could?

Nothing about my own career was ever consciously trying to model anything for anybody else. I was a freelance writer the whole time I was a graduate student, so I published a lot of interviews with cartoonists just for fun. It didn’t necessarily seem like an extension of my academic work. Sometimes those conversations made it into my own academic writing, but I was just sort of doing different kinds of writing in different kinds of venues, which I find very sustaining.

I don’t think that one needs to go talk to a living creator if one is researching the work of that creator. The artist’s voice is incredibly suggestive and incredibly provocative, but it isn’t the final word on anything, necessarily. It’s more like an opening up than a closing down. But I think that boundary can sometimes be hard to work with when you’re a scholar who studies living creators, so I don’t know that I would recommend it. It happened to have been really useful for me.

With your 2012 conference, the focus was on practitioners. Why did you do it that way? You could have just as easily organized a more traditional academic conference.

I wanted theory and practice to be more in conversation. I really didn’t want it to be an arid academic conference where the cartoonists felt like objects. They would sort of show up as objects and the real explainers, the academics, would be there to, like, elucidate everything. That’s not the way I think it actually works. I think theory and practice are in much more fruitful conversation than a lot of typical conference models would indicate.

At the conference it seemed like there were two schools of thought: the people who really seemed to enjoy picking things apart like Art Spiegelman and Alison Bechdel, and then the people who seemed a little more resistant to that mode of inquiry, like R. Crumb and Lynda Barry.

The cartoonists had a bunch of different responses to the conference that got sort of performed in different ways. Lynda was someone who, I think, felt uneasy or uncertain about what an academic conference about comics would do. But it’s worth noting that Lynda is a professor at University of Wisconsin. And the thing that I loved about R. Crumb at the conference was that he had had all this sort of resistance upfront. He sent me these postcards. I hope the conference isn’t too boring. Remember it’s about comic books—that type of thing. But he was so interested. He was calling out comments the whole time from the first or second row, which I just got such a kick out of. I loved having an academic conference with so many shout outs from the audience.

There was a certain tension between high and low (culture) at the conference. The discussion between Crumb and Françoise Mouly (who is theNew Yorker’s art director) about his rejected New Yorker cover was one of the stickiest moments where these ideas were pushing against each other.

“We thought, ‘Rejected by the New Yorker, good enough for Critical Inquiry.'”

I actually loved when they were disagreeing, even though it kind of stressed me out in the moment. Because I felt like, OK, a conference where people disagree is a real conference for people who are hashing out real issues. I didn’t want it to just be a cheerleading for comics conference.

But I don’t think the high/low tension necessarily persists in a way that we can map out onto individual figures. Before the conference, Crumb had a show at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. On the other hand, the New Yorker has done some of the most interesting experimental work in comics under Françoise Mouly over the past 10 years. All sorts of really, really interesting work, like serial narratives that start with the cover and pick up on the interior. So it might be that one of the serious locations for avant-garde work in comics right now is the New Yorker, which is kind of fascinating.

This issue of Artforum [the Summer 2014 issue, which recounts the history of underground comics in between full-page ads for galleries] is kind of a watershed moment in that the art world is marking its interest in comics so openly. It doesn’t necessarily know how to go about it, and I don’t think cartoonists feel entirely comfortable with it. Everyone is a little bit ill at ease, but sort of interested in what could happen.

Do you think this unease with the high/low thing is generational to some degree? Is your impression that younger cartoonists really care about the same issues?

I don’t know if I think that they do care in the same way. Their battles weren’t as hard-won as the battles of people like Lynda Barry and Art Spiegelman and Robert Crumb and Phoebe Gloeckner and people who have been in the trenches doing comics for a long time. I think some younger cartoonists tend to take this primed, open comic-friendly landscape for granted in a way that certain older cartoonists couldn’t.

I think that’s a good thing and a bad thing. The good part is that it’s easier for young people to break into comics. There’s something incredibly democratic and encouraging about that. But I’m a person who always cares a lot about history. I hope the younger cartoonists have a sense of comics history, because the 1970s—the period that basically created the serious adult comics field we have today—weren’t really that long ago.

The rejected cover that Mouly and Crumb were talking about is now the cover of a special issue of Critical Inquiry that you co-edited.

We thought, “Rejected by the New Yorker, good enough for Critical Inquiry.”

In addition to the usual academic stuff, it has transcripts from the conference and original artwork from Lynda Barry and many others. How did that combination come about and how much of a departure is that for Critical Inquiry?

Part of what I was interested in doing was trying to take stock of comics on its own terms. So not just to run an issue that would have sort of arid critical essays on comics, but to try to make a different kind of critical object.

It’s also a different size than every other issue of Critical Inquiry that exists, so that was a major departure. You know, that doesn’t seem like a big deal to the outside world, but in this world it’s a huge deal to have an issue that doesn’t look like any other issue. This is a journal that’s been preeminent for over 40 years.

I’m thrilled out of my mind that we got original art from people like Lynda Barry. There’s a brand-new five-page piece from Phoebe Gloeckner, the first comics piece in a long time from Françoise Mouly, and a brand new comics piece from Justin Green. Just really, really, really exciting stuff. I’m so grateful to the artists.

One criticism you’ve received with regard to the conference and your new book (Outside the Box) is that you tend to feature cartoonists who are too white. More than once, you’ve said that your work really only reflects your personal interests and that no one should consider it canon. Every time I’ve read that, I’ve totally agreed with you. But at the same time, since you’re at the forefront of a relatively new sub-discipline, isn’t anything that you do going to be a de facto canon, even if that’s not what you want personally? Who is in a better position than you to make sure that the canon isn’t just white people?

I don’t mean to be disingenuous when I say these are just my personal choices. I think what I’m assuming is that everybody feels as empowered as I do. And I don’t think one needs to be institutionally empowered here, but that everyone feels like they could publish a book with their own canon of cartoonists or organize their own conference. I’m not trying to be the voice that squashes out other voices. I’m trying to be one voice among many. And I love the idea that someone else could put on a conference and organize it differently, or that someone else would publish a book of interviews and organize it differently, or someone else would edit an issue of a journal on comics and do it differently—which has happened, and which is great. I’m never trying to be the be-all, end-all in terms of the canon. The idea of a canon is always already porous and unstable.

This is oversimplifying a lot, but to me a lot of that criticism has read as men who just rattle off a list of their favorite male cartoonists that you didn’t include in the grouping. I haven’t seen a lot of acknowledgment of the critical attention you’ve given to women like Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Françoise Mouly whose contributions to the form have been sort of overshadowed by their husbands’. Was there a point that you thought to yourself, OK, part of my job is going to be to correct the record and give these women their due?

My appreciation of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Françoise Mouly was really borne out of a place of deeply respecting their work. So it really comes out of my own attachment to the work, but I’m happy that it is also corrects the record, which I think does need to be corrected. I went to stay with the Crumbs [in France]. I think it was in the summer of 2009. I was there to interview Aline, and I think that Robert Crumb got such a kick out of that. The person I was there for was her, and that wasn’t borne out of any desire to correct the record. It was borne out of my deep sense of fascination with her work. I felt like I could sit around and read her comics all day. I was deeply surprised to discover there wasn’t a whole body of critical writing on her.

One of the real benefits of coming to comics from a scholastic perspective more than a fan perspective was that I felt no onus upon me to pay massive tribute to Robert Crumb in my own writing and my own thinking (though I do think he will come up a lot in the book I’m writing now). I just kind of liked what I liked and wanted to figure why I found it so fascinating. I didn’t have this sort of conventional comics history sitting on my shoulders. I think that has earned me some skeptics, but that’s OK.