With the release of Baz Luhrmann’s latest film version of The Great Gatsby, fans and advertisers have gotten really excited about the glitz and glamour of the Jazz Age. Stunning clothes, fancy parties; glorious lifestyles of leisure and sport. Don’t we all wish we could live in West Egg?

Americans trip all over themselves to imitate The Great Gatsby, hosting “Gatsby-inspired soirees” on Long Island and trading recipes to bring 1920s food and drink to the average suburban household.

But isn’t this a little, well, inappropriate? All of this Great Gatsby party time is making some literary critics, or just devoted fans of the novel, a little anxious. Wasn’t the point of the book that all of this stuff was a little wanting? That all of these possessions generated by the surge of new money just made us shallow and cruel?

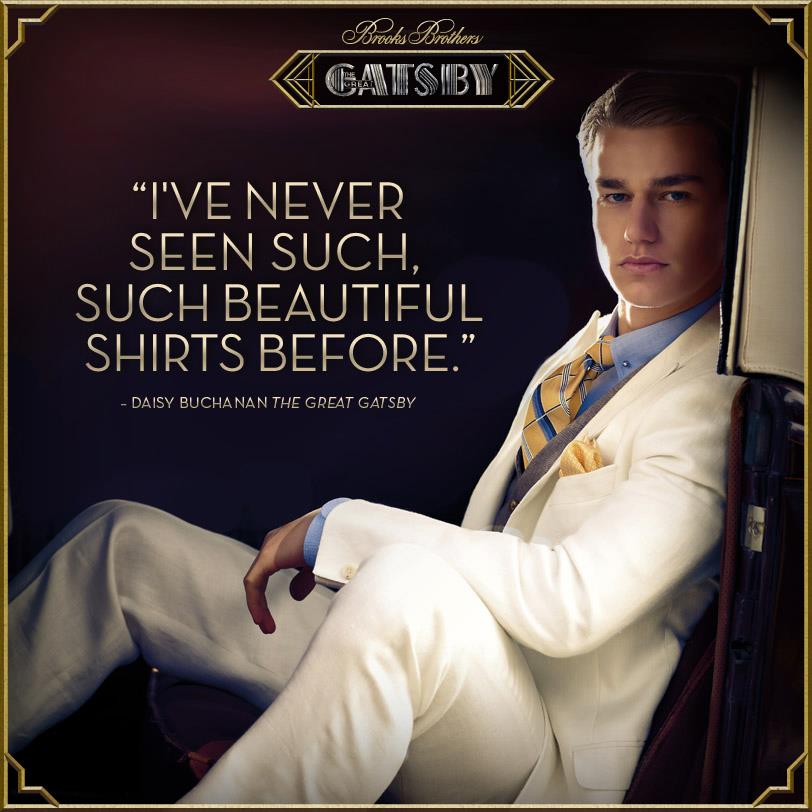

Particularly strange was this Brooks Brothers advertisement:

This, of course, is all wrong. The full quotation, delivered by Daisy Buchanan in a particularly memorable moment as protagonist throws expensive clothes across his bedroom to show her his money, is “It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.” She doesn’t mean she’s impressed by the shirts.

Why aren’t we getting this? Did anybody actually read the book, wondered Zachary Seward at Quartz.

No, don’t worry. We read the book. We even understood the book. We just like to wear the fancy clothes. This wearing-the-luxury-duds even when the luxury represents something wrong, or slightly evil, is nothing new, and it’s also not exclusive to the United States, Gatsby’s self-invented man, aside. Enthusiasm for the clothes of The Great Gatsby don’t indicate blindness toward the tragedy of the story. The tragedy is part of the appeal.

Women have been showing up at costume parties dressed as Marie Antoinette for 200 years. And she’s not exactly an enviable or sympathetic character. It’s not as if women across the world are thinking “Wow, I’d really like to be the hated wife of an incompetent man with ambiguous sexual problems who heads a debt-ridden state on the verge of collapse. That would be awesome.”

No, they just want to wear the diamond necklace and a high powdered wig, not because they want to connect to Marie Antoinette, but because they simply want to connect to a sense of drama larger than themselves.

The costume allows the wearer to envision himself as something else. Not necessarily a better or happier person but, well, perhaps a slightly more interesting person. As Valerie Steele, director and chief curator of the Museum at FIT, once explained:

In traditional societies you’re usually identified according to a category like you’re a married woman versus a single woman, you’re a member of this tribe versus that tribe. In early modern society it tended to be, this is aristocratic dress, this is urban middle class dweller dress, this is peasant dress.

The clothes, it appears, give us freedom to play someone else.

Nowadays you’re identified not just by class or ethnicity or religion, let alone marital status, but rather by different tastes and interest groups. So if you’re into Hip-Hop you’re wearing Hip-Hop-related clothes, if you consider yourself a fashionista you’re wearing certain types of clothes, if you see yourself as a businessman you’re wearing certain kinds of clothes. So, it does provide information, but that information now is more free-floating than it was in the past.

Show who you are by what you wear.

It is not exclusive to novels or movies. It also plays a part in political activism. Witness the success of the 2004 political street theater projects known as Billionaires for Bush. People showed up at events wielding signs ostensibly praising the 43rd president for his billionaire-friendly tax and spending policies while dressed, exaggeratedly, as the super-rich. Even if the actual display of this tended to look a little Gatsby too (there’s nothing easier to find in a costume shop than 1920s evening wear) the point was to dress like you were just rich. Plastic tiaras, tuxedos, champagne flutes, etc. This was supposed to emphasize that George W. favored the rich.

To emphasize the reverse point—that Bush’s policies favored the rich to the detriment of the poor—might be less likely to attract supporters, because it might just be kind of depressing, and the costumes would be uglier. No one wants to go to a Winter’s Bone-themed party. And no one wants to be a meth-head for a costume ball.

All of this doesn’t mean, however, that we don’t get it. Americans don’t want to wear Daisy and Gatsby’s clothes because they think it will render them happy; they want to inhabit the real characters, even if they suffer from noticeable problems.

Indeed the costume party, which dates from the French masquerade balls of the 15th century, has always been infused with an element of the tragic. Anthea Jarvis writes in the Berg Companion to Fashion that in the 1830s a particularly popular costume was that of Mary Queen of Scots, who was deposed as queen of Scotland, kept under house arrest for almost 20 years, and finally executed by her cousin. The queen was appealing because her “story combined legendary beauty, doomed love, and tragic death.” Even earlier, the Swedish King Gustav III of Sweden was actually assassinated at a masquerade ball in 1792, while dressed as a woodsman. This did not cause the popularity of the costume ball to decline markedly.

It’s possible, in fact, that dressing in the luxurious fashions of beautiful, tragic people doesn’t necessarily cause the wearer to identify with actual rich people but, rather, to identify what’s going on. Or, to put it differently, because Jay Gatsby is handsome and stunningly turned out doesn’t make you blind to his flaws. Indeed, the elegance of his presentation make his flaws all the more apparent.

Think of this as the Bret Easton Ellis phenomenon. The more beautiful your stuff, and the more unhappy you seem, tragically, gut-wrenchingly unhappy, the more heightened our awareness of what’s wrong. Luxury might not make you feel better, but it least it makes you feel something. Excess is a form of adrenaline, too.

All of this is nothing new. Indeed, The Great Gatsby itself is pretty clear about the appeal of excess and the emotions it triggers. “Anyhow, he gives large parties,” the character Jordan Baker says of Jay Gatsby. “And I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.” Bigger, grander, more expensive, this is the secret to understanding. Baker might have been wrong, but she appeared to have some idea what all of this was really for.