No more carrying a backpack full of clothing to work, not knowing when or where he’ll be able to shower next. No more living deep down on Chicago’s South Side, a psychological world away from family and friends. No more dreading an eviction because he can’t cover rent.

Santos Acosta III is home.

The 30-year-old Acosta plops down on the plush, green living room couch, while his toddler son, Santos IV, naps in the next room. Outside, in the fading autumn light of the half-gentrifying/half-impoverished neighborhood of Humboldt Park, gangbangers might be swapping drugs for cash as mothers shove strollers along the sidewalk. What matters now, though, is that Acosta and his wife have a place they can actually afford.

“If it wasn’t for this building, I’d be so far west it wouldn’t even be funny,” he says, referring to the less-desirable edge of Cook County.

The story of how Acosta landed this two-bedroom apartment began in 2006, when he and his mother-in-law waited outside in an all-night line to add his name to a list of applicants for apartments in a building that didn’t yet exist. It continued as he filled out reams of paperwork. Then, construction of the apartment project was delayed, and Acosta received a raise at work — good news, except that it pushed him barely above the income limit set for these subsidized apartments. He had to beg his way up the political hierarchy to an alderman who made sure Acosta didn’t lose his spot on the list. And finally, in November 2007, his family moved into the completed building, known as La Estancia.

But there’s a complex tale behind Acosta’s modest new home. Until a few years ago, the lot where La Estancia now stands was occupied by a gas station that had shut down. A developer bought the land, planning luxury condominiums — exactly the sort of gentrification that has sparked political strife in the neighborhood, dominated by working-class African-American and Puerto Rican families. Furious about the idea of high-priced housing at the entrance of a five-block commercial strip calledPaseo Boricua (loose translation: “Puerto Rican Promenade”), residents asked their alderman to put the kibosh on it.

With the future of the condos uncertain, the developer — who had several other projects in the area — put the brakes on. In the past, things may have ended there. But Joy Aruguete, executive director of the nonprofit developer Bickerdike Redevelopment Corporation, offered an alternative: For months, representatives of an alphabet soup of local social service and business groups had been meeting, hoping to plan a project on the Paseo Boricua. The old gas station lot would make a perfect spot.

Bickerdike bought the parcel from the developer and acquired additional land nearby. The Chicago chapter of the nonprofit developer and deal-maker known as the Local Initiatives Support Corporation kicked in a $1 million pre-development loan, and the community convened to hash out an agreement on what the buildings would become. This willingness to collaborate, Aruguete says, was a direct result of the New Communities Program, a $52 million, 10-year effort by the MacArthur Foundation and LISC to improve the lives of residents in some of Chicago’s most distressed neighborhoods, including Humboldt Park and its La Estancia complex.

Acosta knows little of the saga behind his apartment and the existence of the New Communities Program. He’s hardly alone; he’s one of thousands who’ve benefited from a long chain of efforts to rebuild Chicago communities coordinated and overseen, often far in the background, by MacArthur and LISC.

For decades, hordes of brilliant do-gooders have tried and largely failed to solve the myriad problems — from violence and diabetes to joblessness and educational deficits — afflicting the poorest residents of the richest country on Earth. The failures of these programs, many begun as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society push to end poverty, are well known. They were often unrealistically short-term, suffered from lackluster management and relied, to a remarkable degree, on untested theories. And they were so generally unsuccessful that they created a political backlash exploited by both Republican and Democratic presidents.

After years of caution, many foundations and governments are renewing their interest in comprehensive approaches to poverty and social ills. Over the last six years, New Communities has attracted $500 million in grants and loans for programs in 16 Chicago neighborhoods. Evidence of change appears in the form of everything from a revamped HIV/AIDS task force to community bike rides.

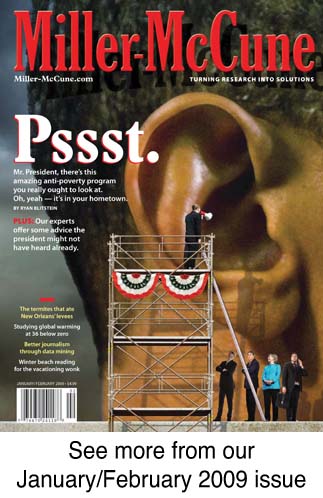

LISC’s national office, heartened by New Communities’ accomplishments, is adapting it for use in 10 other cities, including Milwaukee and Oakland. Meanwhile, the California Endowment and Michigan’s W.K. Kellogg Foundation have announced large-scale plans founded on similarly integrated approaches. And President-elect Barack Obama has pledged to create 20 “Promise Neighborhoods,” modeled on the Harlem Children’s Zone, which employs wide-ranging efforts to aid youth within a targeted area. “People are recognizing that if you’re really trying to talk about community change, you can’t just do it by housing or physical development or by reducing crime or (improving) public health,” says Woodstock Institute consultant Sean Zielenbach. “They’re all inherently interrelated.”

Despite encouraging progress, it may be decades before New Communities and similar programs will produce anything close to major change. The field’s brightest minds, in fact, are far from certain these new anti-poverty approaches will work better than past attempts. But for the first time in a long time, experts are expressing optimism that a new approach — one borrowing from the methods that venture capitalists use when funding startup companies — could help move entire communities from decay to something that at least resembles economic normalcy.

Questions about the effectiveness of attempts to help the poor are as old as charities themselves. The settlement houses of the 19th-century Progressive Era — Chicago’s Hull House and the Henry Street Settlement in New York, for example — offered food, shelter and education to the urban poor and recent immigrants. Later, pioneer mega-industrialists — think Carnegie and Rockefeller — steered their endowments toward programs aimed at the underclass. None of the programs provided much more than temporary assistance, a small bandage for the gaping wound of systemic poverty.

Post-World War II prosperity brought optimism to much of the country, but one of its most dynamic features — suburbanization — drained cities of affluent people and businesses, as well as the taxes they paid. One-third of Brooklyn became blighted. The famed architecture of Chicago’s downtown Loop was surrounded by a three-mile-wide band of wretchedness. During the 1960s, the frustration of the mostly black poor boiled over into widespread rioting, and a presidential commission warned that America was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

Inner-city decay increased the urgency of government- and foundation-funded urban revitalization programs and the elevation of poverty research into a well-funded social science. Researchers produced heaps of data, but the best ways to address the core problems of entrenched poverty continued to elude the field.

“As a country, when we’ve worried about poor people and poor places, by and large we haven’t stuck with any single, well-thought-out, consistent approach and stayed with it long enough to learn anything about whether it works,” Wayne State University professor Avis Vidal says. “We’ve been at this on and off for the better part of 50 years and have learned almost nothing.”

The recent history of big anti-poverty ideas and solutions is dismal. Urban renewal, which demolished central cities’ low-income housing to make way for “better” developments, was derided as “negro removal.” Despite $7 billion spent between 1965 and 1974, urban renewal destroyed more housing than it created, with neighborhoods often left in ruins.

President Johnson put forward the goals of his Great Society in May 1964, and more than 40 years later, it has a decidedly mixed legacy: The early childhood learning program Head Start continues to help millions, while the long-forgotten Model Cities effort, aimed at comprehensive redevelopment and change, ran into conflicts between local governments and neighborhood groups. The Ford Foundation’s Gray Areas, a comparable private initiative, made little headway, partly because it failed to adequately consult the residents it aimed to help.

Grass-roots-oriented efforts didn’t fare much better: Community organizers united residents, and community development corporations built housing. But limited budgets kept most of these programs from extending beyond the ad hoc; almost none effected anything close to systemic change. While these endeavors collectively aided tens of millions of people for a time, in the long term none cured the larger illness. President Ronald Reagan ended the War on Poverty, essentially declaring poverty the victor.

“We haven’t alleviated poverty,” says Bob Giloth, director of family economic success at the Annie E. Casey Foundation. “One thing people always ask you in this business is, ‘Show me the neighborhood where that’s been done.’

“Where do you point?”

In the fall of 1999, shortly after he took the helm of the MacArthur Foundation, Jonathan Fanton met with Susan Lloyd in her office. Lloyd had been working for years on the Building Community Capacity program, which targeted funding toward five Chicago neighborhoods. Like most initiatives aimed at struggling neighborhoods, its results had been mixed.

At the time, dot-com-fueled millennial optimism was everywhere, and the buzz around social entrepreneurship and innovative philanthropy had foundation heads like Fanton thinking big. With MacArthur’s $7 billion in assets, the former history professor and university administrator had cash to deploy. How much money, he asked Lloyd, would it take for Building Community Capacity to achieve a critical mass toward serious change? And how much could the revitalization of these areas really affect the lives of their residents?

Around the time Lloyd was rethinking Building Community Capacity, Amanda Carney, then leading a LISC project to help residents in three Chicago neighborhoods, reported some good news. Lloyd had given LISC $160,000 for a nine-month project to create local parks and open-space plans. With little fanfare, the community groups had assembled impressive land-use plans — and also quickly convinced the Chicago Park District to put in $1.7 million to bring the plans to fruition.

Even in a minor community-development project, such rapid success was uncommon. LISC’s leaders, though, had begun to see similarly heartening outcomes elsewhere within an experiment called the New Communities Initiative.

The program was much like MacArthur’s Building Community Capacity — with one crucial difference. Instead of funding a bevy of agencies in a neighborhood, LISC was giving the bulk of each area’s funds to a single lead group, which then worked with other organizations to parcel out grants. The theory was that a single, in-the-neighborhood broker could do a better job of gaining trust, striking deals and staying accountable than multiple smaller groups. And the theory was proving true in practice.

Lloyd and her team began talking with LISC’s management about combining the best of the two programs — and everything else that had come before in communitywide attempts to fight poverty. Most foundation grants last a year or two. The new project would endure much longer. Many philanthropies target anti-poverty and redevelopment programs to specific areas, such as asthma reduction or the fostering of entrepreneurship. MacArthur and LISC would simultaneously invest in numerous efforts, drawing on the experience of programs called comprehensive community initiatives, which emerged during the late 1980s and were based on the consensus that social ills are interconnected.

The all-at-once approach may seem obvious, but the social service world rarely works holistically. There’s a field called work force development, for example, that has to do with job creation and vocational education. Work force development has its own experts and practitioners, its own community-based organizations, its own funding streams. Analogous, separate systems exist for housing, crime prevention and children’s mental health. Everything is siloed; because they are funded separately and have different priorities, social service groups seldom interact with one another, even within a single neighborhood.

In places like Baltimore and Battle Creek, Mich., comprehensive community initiatives have aimed to cross-pollinate, striving for community transformations larger than the sum of the individual programs involved. In practice, however, they often fell short, running into power struggles among foundations, grant recipients, government and residents.

The planners of the New Communities Program knew they had to create something different. They hoped to unite two streams of philanthropy that had been flirting with each other but never quite fused: traditional social work, like preventive health care, and economic efforts, such as business development.

To help settle on best methods, the group held months of round-table discussions during 2001 with poverty research luminaries from Harvard, the University of Chicago and other universities. Lloyd and LISC/Chicago executive director Andy Mooney traded scholarly articles and popular books on related subjects — Hidden Order by economist David Friedman, for example, and Robert Putnam’s social capital research that became Bowling Alone. Lloyd cites a particularly influential series of studies stemming from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, which tracked people’s lives, health and relationships. In one crucial paper, project researchers concluded that what they called “collective efficacy” — trust, neighborliness and willingness to enforce community norms (such as not loitering on street corners) — was more likely to predict a positive outcome than either the poverty level or the race of the people involved.

Many vital ideas were rooted in a report, “Changing the Way We Do Things,” issued in 1997 after LISC’s board brought Chicago’s community development experts together for a yearlong, fieldwide rethink. The discussion, as well as the framework of the final document, was largely built on two early presentations: one by former Missoula, Mont., Mayor Dan Kemmis and the other by a not widely known, newly elected Illinois state senator named Barack Obama.

By 2001, the architects of the New Communities Program decided to use an “intermediary” approach, with MacArthur providing the bulk of the funding and LISC making grants to 14 lead agencies in 16 neighborhoods. The agencies would lead a quality-of-life planning process to figure out what residents and local groups wanted and which people or groups should get grants. In most cases, that meant helping existing groups coordinate; in others, the program would create brand-new groups.

New Communities also borrowed the notion of venture capital grant making from a successful Surdna Foundation project in the South Bronx. Typically, philanthropists dole out money for specific projects, do what they can to aid the recipients and then assess whether the projects succeed after a year or two. New Communities would be more like a Silicon Valley venture capital firm, investing seed money in an idea. If the project failed at first, New Communities might provide money for a new line of attack. If the project morphed into something different from what had been proposed but nevertheless worked, the funders would encourage it. If the project progressed and grew, New Communities would help find other investors. If it succeeded, they’d help it expand or replicate it.

This nimble strategy seemed ideal for a program managing dozens of simultaneous projects. To aid in evaluating grantees in real time, MacArthur funded a team of writers — including seasoned ex-Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times wags — to provide sometimes-blistering internal critiques. The MacArthur Foundation pledged a total of $21 million over five years, which LISC would eventually leverage, bringing the stage-one total in government funds and private financing to more than $250 million of investment in new housing, store and office space and public facilities. Last year, MacArthur added another $26 million to finance a second stage of the overall project and has funded millions’ worth of related projects in the same neighborhoods.

Early one Saturday in October, Karin Norington-Reaves stands behind a lectern in the meeting room of a 100-year-old church, attempting the local political equivalent of herding cats. Three dozen people, ranging from clergy to housing activists, sit two per table, most ready to tell her she’s wrong.

“You are the die-hard, core group that comes out every single time, and we really appreciate you being here,” she says.

When Norington-Reaves signed on last year as chief of staff to newly elected Alderman Willie Cochran, organizing a community nonprofit was not in her job description. But the New Communities Program was advancing too slowly in Washington Park, a neighborhood adjacent to the University of Chicago (and virtually in Obama’s backyard) where half of residents live below the poverty level. LISC has had to swap out and replace a handful of lead agencies — evidence of the program’s imperfection but, perhaps more important, proof that it actually holds grant recipients accountable for errors. LISC’s leaders asked Cochran and Norington-Reaves to incubate a new lead agency inside the alderman’s office.

Until the Washington Park Consortium launches next year, she is in charge. This morning, the participants are offering critiques of a draft of the quality-of-life plan for Washington Park; it’s a document that will define the neighborhood’s redevelopment strategy for the next five years.

It seems as if everyone has his or her pet project or cause that the final plan absolutely must mention — adult sports leagues, rent-to-own housing, medical research. Many nitpick over language that was supposed to be settled after months of work by smaller committees. Norington-Reaves is the arbiter of what’s relevant, what’s worth a five-minute minidebate and what should be relegated to the comment sheets.

Several participants quibble with a section about holding residents “accountable.” Doesn’t that, they ask, blame the community for problems not of its own making? Norington-Reaves explains that residents want accountability if, for example, kids throw bricks at cars.

One woman responds that the entire plan feels negative and oppressive, overemphasizing problems instead of highlighting solutions. A handful of others echo her disapproval.

“I hear what you’re saying,” Norington-Reaves says, “and we’ll wordsmith it.” And then she moves on.

When outsiders create revitalization strategies, leadership and plans are often pushed down to residents and community groups. Figuring out how they’re all going to function in concert comes later. New Communities turns that process on its head; everyone who’s interested is invited to assess the neighborhood’s needs and assets and to help develop a plan for fixing the problems. At the outset, there are few preconceptions; the only guides are facilitators from LISC, the lead agencies and some outside consultants. “The genius of this approach is to say, ‘We will let the range of neighborhood problems, as defined by the community, determine what the response should be,'” says Malcolm Bush, a researcher at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall Center for Children.

Because it’s open-ended, this kind of planning looks messy. But in several neighborhoods — even those, like Washington Park, where a lead agency is developed from scratch — the process has led to realistic plans and significant progress. “What doesn’t work is the cookie-cutter approach, when a foundation or intermediary says, ‘Here’s the way we do it, and we’re going to do it the same everywhere,'” LISC director of programs Joel Bookman says.

In nearby Englewood, more than 650 people participated in a yearlong quality-of-life planning process that’s beginning to bear fruit. Once home to the 63rd and Halsted shopping district, the retail center of Chicago’s South Side, Englewood became a poster child for the government failures that decimated neighborhoods across the Rust Belt. After suburban malls cut into Englewood’s retail sales, the city directed $17 million in redevelopment funds to turn the shopping district into a pedestrian mall. But poor siting of parking lots meant little improvement, and the displacement of 250 middle-class homes instigated a protest march led by Martin Luther King Jr.

A pair of much-hyped revitalization efforts during the 1970s and 1980s left the area in even worse shape: A major hospital closed, and thousands of homes were abandoned. Steel plants and stockyards shut down; between 1975 and 1990, Englewood lost half its jobs. Violent crime skyrocketed, and locals dubbed a two-block stretch “Little Beirut.” Between 1970 and 2000, population plummeted from roughly 90,000 to 40,000.

Yet the Rev. Rodney Walker, executive director of Teamwork Englewood, thinks this neighborhood still has a fighting chance. From an office near the hallowed corner of 63rd and Halsted, the local pastor and former health care administrator presides over New Communities’ efforts toward revival. “People are, for the first time in a generation, feeling that change is possible,” Walker says.

It’s more than empty talk. In 1999, the city announced a $250 million redevelopment plan that has already relocated Kennedy-King College to 63rd Street. New housing has popped up, and a new shopping complex will soon replace several block-sized vacant lots. Instead of begging for investment from the outside, Walker finds himself helping developers partner with the community to decide which stores belong in the mall. Kennedy-King is now home to Sikia, the first non-fast-food restaurant to open in Englewood in 20 years, operated by the Washburne Culinary Institute.

Walker’s Teamwork Englewood has become the hub of unconventional deals struck among schools, governments, community agencies, corporations, law enforcement organizations, religious groups and residents. He helped lure $100,000 from the city for a prisoner re-entry center, which aids recent parolees and ex-convicts in cleaning up their records and finding jobs. In another program, paid for by the Metropolitan Agency for Planning, Englewood students spent a summer mapping the large number of Clear Channel billboards that advertised cigarettes and alcohol in Englewood. Block club members called Clear Channel to complain, and the company pledged to replace some with health-oriented promotional messages developed by locals. Unlike traditional community organizations, Teamwork Englewood doesn’t have to wait six months until the next grant-making cycle to respond to change; it just approaches LISC staffers, who have discretion to make immediate grants as large as tens of thousands of dollars.

At City Hall, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley has embraced the New Communities effort, asking a deputy chief of staff to act as his liaison with LISC and lead agencies. A few years ago, after a series of shootings rocked Englewood, Daley asked city agency heads to develop ideas to address the crisis, with Teamwork Englewood playing a coordinating role in the community.

For all Walker’s accomplishments during barely a year on the job, though, he’s realistic about the prospect of digging Englewood out of a 60-year history of trouble. “We’re looking at several generations of economic challenges, financial challenges, social challenges,” he says. “I think there’s no quick, easy fix. I think that’s fantasy. I think it sounds good, but in reality it’s 20 years of change.”

On unsightly blocks southwest of Walker’s office, children traipse home from school across vacant lots, passing boarded-up buildings and men drinking from 40-ounce bottles in paper bags. In one church parking lot, a bespectacled young man named Qaid Hassan rests on a lawn chair, a laptop perched on his knees.

He’s the manager of this farmer’s market, created by Teamwork Englewood. Its impetus was Englewood’s “food desert” status — the neighborhood lacks options for healthy eating. From the lot’s two tables, farmers sell fresh collard greens, garlic, sweet potatoes and other produce. Hassan, a University of Chicago graduate student, is among the vast crop of twentysomethings at the bottom of the New Communities pyramid who see what happens when the rhetoric actually meets the residents.

During the course of an hour, only a few customers appear. Recently, some vendors have become so disappointed with the scarcity of buyers that they stopped coming. Hassan and Walker hunted for a location closer to public transit and foot traffic, but bureaucracy got in the way, so the market’s stuck here, at least for this year. As Hassan laments weeks later, after the market has closed for the winter, “I didn’t achieve what I wanted to achieve, what I had in mind, what I envisioned.”

Scenes like this contradict the cheery marketing materials produced by New Communities. The failures of some New Communities efforts leave the program’s leaders in an awkward position: Every time they highlight accomplishments, they risk coming off as overly upbeat about a program that faces daunting obstacles.

The MacArthur Foundation can truthfully point to signs of overall progress: During 2007, for instance, school graduation rates increased in two-thirds of the neighborhoods served by New Communities. The rate of business growth was up 2.5 to 3 percent in all the areas, versus a 0.5 percent decrease citywide. A 2006 report on New Communities commissioned by MacArthur concluded, “The overall process, while not perfect and still evolving, has worked remarkably well.”

The program, though, confronts serious challenges just by virtue of its ambition. In many of the communities, it has created an infrastructure network that’s incubating a range of promising ideas. But there’s little evidence the projects can attract enough outside investment to mature into independent, sustainable organizations. As Craig Howard, MacArthur’s director of community and economic development, acknowledges, “It’s not clear where the resources are going to come from.”

As time passes, residents flow in and out of neighborhoods; a typical American moves about once every five years. So, too, do the people in charge of nonprofit programs — both Lloyd and Carney have left, on good terms. Such fluidity adds to the challenge of sustaining a complex, massive effort like New Communities, particularly when macroeconomic forces can wreak havoc on the best-laid plans. The foreclosure implosion, for instance, has so ravaged New Communities neighborhoods that in October, MacArthur announced a $68 million loans-and-grants package directed at the problem. The overall credit crisis and recession may set some of the target neighborhoods back years.

Certain academics who study poor communities express skepticism that any locally focused initiative, no matter how well conceptualized or well funded, can effect true change, even in the best of economic times. During recent decades, the nation’s political economy has featured stagnant wages for low-paying jobs, fast-rising health care costs, a limp job market for low-skilled workers and frequent layoffs by even the sturdiest corporations.

In America’s inner cities, program after program has swum against this tide. But without systemic economic change — on tax, welfare and regulatory policy, among other issues — the approach may not work.

“There’s this persistent search for the better intervention: ‘Let’s fix the intervention; let’s tweak this piece to make it more comprehensive; let’s make it a long-term investment,'” says Alice O’Connor, a social policy historian at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “(But) they’re intervening in a situation in which they have limited capacity to deal with larger structural and political forces that are undermining these communities.”

If New Communities does have a huge impact, it will be difficult for MacArthur and LISC to prove. Simple charity work is easy to evaluate: If you’re a low-income housing developer, your funder just counts up the number of units you built. Comprehensive community change, however, is multifaceted; even statistical experts have trouble appraising what’s happening, much less what is responsible for change. It’s impossible to apply the traditional rigor of social science experimentation: There are no control groups or random assignments. Instead, there are a nearly infinite number of variables, and everything is dependent on just about everything else.

It’s not hard to see why program officials are wary of making sweeping statements. Even as LISC adapts New Communities methods to other cities around the country, MacArthur’s Julia Stasch, vice president of human and community development, says it’s a program with promise but not enough proof of expansive success. “We’re actually a little bit hesitant about saying that it’s a national model that others should emulate,” she says.

It took years just to produce the quality-of-life plans, and six years after New Communities launched, even the most advanced neighborhoods have only recently begun implementing the ideas in their plans.

“We’ve got to be cautious,” MacArthur’s Howard says. “We’re still in the startup period.”

Based in an office just north of the Loop, Bookman and Susana Vasquez, LISC New Communities Program director, probably have the most complete picture of the immense initiative. For them, New Communities is less a single startup than a vast network of them.

Both joined LISC well after New Communities had launched, fully aware that the project was tackling problems that had bedeviled colleagues for decades. Vasquez, who has thick, curly black hair and pearl earrings and was in September about-to-burst pregnant, had spent years as a nonprofit administrator and taken a midcareer break to study at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Bookman, ever the stiffly affable civil servant, has been involved in community development for about 30 years, mostly on the city’s northwest side.

Since then, they’ve seen small ideas grow into something far beyond their expectations. A youth basketball league in a single neighborhood (Pilsen) has expanded to seven leagues and a citywide tournament, promoting safety, building relationships between residents and police and acting as a forum for health fairs and arts activities. A summer job program for 100 kids in Englewood, instigated in response to neighborhood violence, has expanded to hire 660 young adults in several neighborhoods.

The 16 New Communities neighborhoods are changing at varying paces partly because, for all their common problems, they’re dissimilar. In Englewood and Washington Park, little social service infrastructure or collaboration existed before New Communities. In Humboldt Park, where Acosta lives in La Estancia, social service organizations and connections were already well established. The Humboldt Park quality-of-life plan was focused on preserving local culture and identifying overlooked problems. For example, a 2004 report by the local Sinai Urban Health Institute alerted the community to serious health issues — one-third of residents smoked, one-third were obese and 14 percent had been diagnosed with diabetes. Bickerdike Redevelopment and its partners set up a Communities of Wellness project in which 50 area organizations — from community groups to major hospitals — coordinate efforts on issues that include asthma and HIV/AIDS.

But Communities of Wellness isn’t an anomaly. On any day or week or month, New Communities includes dozens of ventures aimed at improving quality of life, with many more under development. For Bookman, Vasquez and their colleagues, just keeping track of the intricacies of the New Communities world is a nearly full-time job. They watch as each neighborhood, little by little, chips away at some tiny part of an intractable set of problems that, at the beginning of a recession, often seem only to get worse.

“Can we control these systemic things? Absolutely not. What we can do is make a little difference in lots of different places,” Bookman says. “In community development, what we do is really on the margins. But the margins are everything.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.