I was first diagnosed with depression at the age of 17. Or, to be exact, as having non-clinically significant depressive symptoms. Eight years later, immersed in the stress and despair that is the final winter of a Ph.D. in wet and gloomy Cambridge, England, I really committed to my melancholy and made the jump to the professional leagues.

While cognitive behavioral therapy and a daily dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) worked for me, an estimated 20 to 40 percent of people with depression do not improve with the standard treatment options currently available. Of course, not everyone experiences depression in the same way, with about five percent of the population expressing only a couple of symptoms for a few weeks or months, while another four percent will have chronic, full-blown major depressive episodes that can come and go for years. Regardless of the severity of their symptoms, with at least one out of every 10 Americans being diagnosed as depressed at some point in their lives, this still leaves between 6.3 and 12.5 million people in the U.S. alone who are not getting—or will not get—the treatment they need.

The conventional premise behind depression is that it is caused by a depletion of the neurochemical serotonin in the brain. The theory goes that a combination of specific genes affecting our underlying brain chemistry dictates our responses to general life stressors, which can then place us at a greater risk for developing depression if the circumstances are right.

While some people have naturally higher levels of serotonin, making them more resilient to things like a bad break-up or losing their job, others have greater difficulty coping, getting sucked into negative thought patterns, ruminating about an event, and eventually experiencing feelings of hopelessness, anhedonia, and moroseness.

A combination of specific genes affecting our underlying brain chemistry dictates our responses to general life stressors, which can then place us at a greater risk for developing depression if the circumstances are right.

According to this line of thinking, certain life circumstances might make anyone feel down for a little awhile, but it is your low serotonin levels that keep you there. Alternatively, feelings of depression themselves might affect your neural chemistry, depleting you of serotonin and even causing changes in the structure of your brain.

Regardless of the direction of cause and effect, standard treatment for depression typically involves boosting serotonin levels in the brain, preventing your neurons from taking the chemical back up into the cell after its release, meaning that there is more of it floating around in your synapses for longer. But if the serotonin supposition were true, treatment rates with SSRIs should be a lot better than they are currently. Additionally, the perplexing two- to six-week lag period before any tangible effects from the drug kicks in wouldn’t exist (SSRIs increase serotonin levels almost immediately, but benefits aren’t typically seen for at least another few weeks).

In short, it appears that there’s a lot more going on in the depressed brain than originally thought.

With these questions in mind, the last decade has seen a shift away from the serotonin hypothesis, and researchers have begun exploring other facets of brain structure and chemistry that might better explain the underlying roots of the disorder. This includes new drug therapies investigating psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic mushrooms, and ghrelin, the body’s major hunger hormone, as alternatives to SSRIs, as well as using transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, to zap the brain in a couple key areas to alleviate symptoms.

PSILOCYBIN

Psilocybin’s effect on the serotonin system is what gives so-called magic mushrooms their hallucinogenic properties, like the perception of psychedelic colors or visions that the walls are breathing. This serotonin activity also theoretically contributes to the drug’s ability to increase positive mood and feelings of interconnectedness and wellbeing.

Previous research looking at the effects of psilocybin in the brain has also shown that it suppresses activity throughout several key neural networks, and it is this ability, combined with the drug’s stimulation of serotonin, that has attracted attention in recent years as a possible treatment for depression.

Over-activity in certain areas of the brain, particularly in the amygdala—a region that is essential for processing emotion, particularly negative ones—is related to feelings of anxiety and depressed mood, and depressed people typically show increased arousal in this area, making them hyper-sensitive to stress or threats. Thus, decreasing neural activity throughout the brain could potentially also dampen over-responsiveness, resulting in a possible two-fold anti-depressant effect with the spike in serotonin.

Psilocybin was first isolated from Psilocybe mexicana. (Photo: Sasata/Wikimedia Commons)

Researchers from the University of Zurich decided to test this mood-boosting ability of psilocybin by giving a small dose of the drug to 25 healthy people while they were viewing negative and neutral emotional pictures in an fMRI scanner—like photographs of car accidents, weapons, and mutilated bodies, compared with mundane images of people, animals, and everyday objects. This task commonly results in greater amygdala activation, the unpleasant pictures increasing stress levels. Sure enough, when the participants were on the drug (versus a placebo session) they had less activity in the amygdala while looking at the pictures, although there was no difference in activity between the negative and neutral images, meaning there was no added effect of psilocybin during the stressful condition. The participants also reported an increase in positive mood during the drug session, and these feelings of wellbeing were related to the decrease in amygdala activity.

While the science all seems pretty sound, there are a couple of big problems with the study that need to be addressed before we all start eating mushrooms to help cure us of the blues.

With at least one out of every 10 Americans being diagnosed as depressed at some point in their lives, there are between 6.3 and 12.5 million people in the U.S. alone who are not getting—or will not get—the treatment they need.

First, all of the participants were healthy volunteers, none of whom were currently diagnosed with depression. Thus, it is impossible to know whether the same effect would be seen in people who are actually clinically depressed, or if the boost in positive mood on psilocybin would be enough to have an impact in treating serious depression.

Also, the researchers don’t mention a pretty large aspect of using psychoactive substances—the hallucinations. There is no mention in the paper about how strong the effects were and whether the participants found it unpleasant or not. What’s more, it’s unclear how long these mood-boosting effects would last. Would you have to trip every day to get any benefit, or would there be a carry-over effect for a couple of days or weeks? So while initially the study’s results look promising, there are a lot of follow-up questions that need to be answered.

GHRELIN

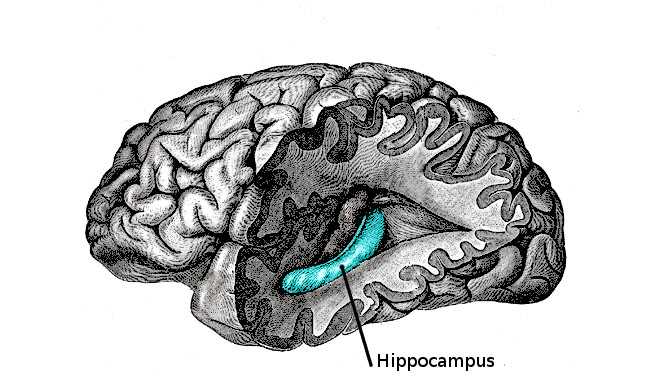

Another area of the brain that has received a lot attention in depression research is the hippocampus, a region most famous for its role in forming new memories but that is also involved in regulating mood. Several studies have shown that in depressed people, the hippocampus is both smaller and less active than in healthy people, and things like chronic stress and social isolation—key triggers for depression—are known to prevent the development of new cells in this area.

Healthy behaviors like exercise and being in a socially and intellectually stimulating environment—activities that can colloquially help protect against the development of depression—have also been shown to foster cell growth in the hippocampus. In fact, one theory posits that SSRIs’ antidepressant effect is actually achieved through their facilitation of new cell growth, particularly in the hippocampus. Thus, a new line of research for depression treatment is aimed at looking at encouraging neurogenesis in this area.

Your hippocampus is located in the medial temporal lobe of the brain. (Photo: Public Domain)

While perhaps not the most obvious choice, one new study has looked at the role of ghrelin, one of the body’s major hunger hormones, in hippocampus cell development and resilience against depression. Normally, ghrelin is produced when we’re hungry, signaling to our bodies that it is time to eat, but other external factors can also influence its release. Ever felt the need to binge on nachos and M&M’s before a big exam? Stress eating is thought to be caused by an increase in ghrelin when we’re feeling anxious, our brains telling our bodies to load up while we’re under pressure. But beyond just giving you a bad case of the munchies, this surge in ghrelin may actually be acting as a protective factor against the development of depression from either chronic or acute stressors.

Circling back to the hippocampus, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center decided to test this theory using four different groups of mice. They genetically manipulated two of the groups so that their cells no longer produced ghrelin and then researchers placed some of the mice—half of which had normal ghrelin levels and half that did not—into a high-stress environment. Even on first glance, the mice without ghrelin appeared to be more anxious than the controls, cowering in the corners and expressing other mouse-like symptoms of depression.

While some people have naturally higher levels of serotonin, making them more resilient to things like a bad break-up or losing their job, others have greater difficulty coping, getting sucked into negative thought patterns.

Comparing the brains of the four mice groups—a combination of “wild” or ghrelin-deficient, and stressed or left alone—both groups of stressed mice showed a decrease in hippocampus size compared with the unstressed mice, but the ghrelin-deficient stressed mice had by far the biggest reduction, with significantly fewer brain cells than their wild stressed counterparts. Interestingly, there was no difference in hippocampus size between any of the un-stressed mice, regardless of their ghrelin levels—only in those that had been stressed.

The researchers think that this effect is driven by a protective influence of ghrelin on the development of new cells in the area; specifically, that ghrelin helps prevent the death of these new cells that can occur with stress. Confirming this theory, the stressed ghrelin-deficient mice had significantly higher levels of certain proteins that signify cell death than any of the other three groups. Taken together, this suggests that stress can result in cell destruction in the hippocampus, particularly in young cells, but that ghrelin crucially protects against this kind of neuronal suicide and the accompanying symptoms of depression and anxiety that are associated with stress.

So far, this research has only been done in animals, so it’s unclear if the same effects would be seen in humans. Additionally, the side effects of feeling hungry all the time and the likely resulting weight gain from increasing ghrelin would probably put some people off, so more research is needed before doctors start prescribing starvation and binges as a viable treatment option.

TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATION

Another alternative to SSRIs is focused on changing activity in the brain using magnets instead of chemicals or hormones. While electroconvulsive shock therapy has given neural stimulation a bad name, developments in this technology using magnets rather than electricity has opened the door for safe, localized, non-invasive treatment options.

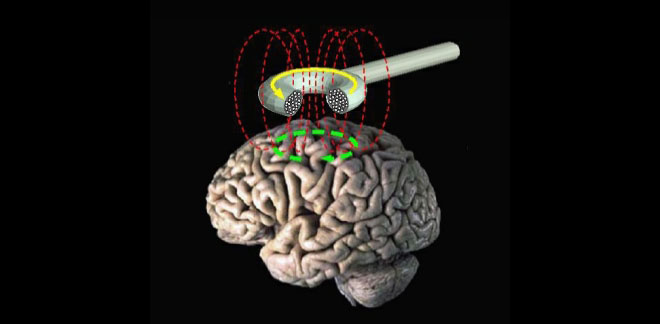

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (schematic diagram). (Photo: Public Domain)

TMS uses magnetic pulses to either ramp up or tone down electrical activity in the brain—activating or suppressing certain key regions. Severalstudies have shown that when these magnetic pulses are applied specifically to the left dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), TMS is as effective as antidepressants at alleviating symptoms of depression and improving quality of life.

The dlPFC is located on the top, outside part of the brain, positioned approximately over your temple at your hairline, and it is essential in working memory and attention, as well as aspects of self-control and future planning. Several studies have also shown that activity in the dlPFC is depressed in people with, well, depression, so TMS is used to increase activity in this area.

While cognitive behavioral therapy and a daily dose of SSRIs worked for me, an estimated 20 to 40 percent of people with depression do not improve with the standard treatment options.

Researchers are still unclear how exactly TMS works as an antidepressant, but they think it has to do with the connections between the dlPFC and other areas in the brain that are involved in emotion. This means that activation of the dlPFC can affect these networks further downstream, altering activity in regions like the amygdala that are involved in stress or emotion and that might be contributing to feelings of depression or anxiety. This includes the potential for influencing the release of serotonin and other neurochemicals that travel through these areas.

One problem with TMS is that it requires a substantially greater time commitment than just taking a pill—zapping your brain with magnets not exactly being something you can do at home. This means having to go in to the doctor’s every day for at least six weeks to receive the treatment, which can be difficult to get people to follow through with. Because of this, TMS is currently only used as an alternative when SSRIs fail.

While each of these new treatments tap into different circuits in the brain, they all still seem to potentially interact with the serotonin system in one way or another. And so although all of these new options have significant potential for depression treatment, none of them are simple or foolproof enough to become the new standard of care, meaning the search continues for a better way to help all 121 million of us who suffer from the affliction worldwide.