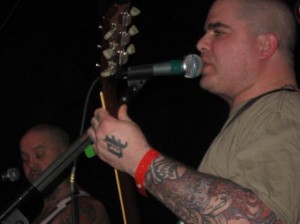

In an image from MySpace, Wade Michael Page is shown playing with the band End Apathy.

The recent shooting at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin has brought sudden attention to one of the most underground music scenes in America: hate rock. Wade M. Page, the man who killed six people and wounded three others in a shooting rampage on Sunday, was the front man of a white supremacist band called End Apathy and belonged to another called Definite Hate. In a 2010 interview posted to his record label’s web site, Page—who killed himself at the scene in Wisconsin—said he became involved with the white power music scene beginning in the early 2000s, and that he had occasionally filled in on guitar and bass for bands such as Celtic Warrior, Radikahl, Max Resist, Intimidation One, Aggressive Force, and Blue Eyed Devils. He also performed at hate rock fests across Europe.

Shortly after Sunday’s shooting, I spoke to the former singer of Intimidation One, one of the bands on Page’s list of collaborators. The singer said Page played bass and guitar for the band on a European tour in the late ‘90s. “I played over 200 shows with that dude,” said the singer. “He was one of the most mellow guys you could know, but he would get crazy when he was drunk.”

Though many Americans first learned of the white supremacist music scene via news about Page’s shooting spree, hate rock has been around since the 1980s, providing a rallying point for white supremacy and serving as a significant vehicle to advance the neo-Nazi movement. As a sociologist, I have spent most of my career studying the skinhead subculture, and as part of that research, I’ve had plenty of occasion to observe the hate rock music scene up close.

While their music is protected by the First Amendment, hate rock bands are unwelcome at most music venues, so a typical show takes place either in someone’s basement, at a so-called “white family picnic” held on the back 40 acres of someone’s private land, or as part of a white power music festival. (Hammerfest is one of the biggest; Page played the festival at least once.)

As Page’s hate-rock resume makes clear, the white power music scene is small, rudimentary, and made up of virtually interchangeable parts. Though members of the scene have made sporadic forays into epic “black metal” and even folk, most of the music is solidly punk rock, with minimal chord changes and lots of shouting. Hence it’s not exactly hard for someone like Page to fill in for another band—and it’s often necessary. Twenty years ago, when I was working on my doctorate by studying the skinhead subculture as an undercover researcher, I was abruptly drafted one night to sing onstage with a skinhead band after the lead singer had become too drunk to stand up. Since I knew a lot of old punk rock songs, I made do by steering the band towards covers of songs by non-racist punk bands like the Sex Pistols and the Ruts.

If the hate music scene has a geographic hub, it is in the post-industrial rust belt, where narratives of white decline have a particularly sour resonance. Two prolific distributors, Diehard Records and ISD Records, are both based in Ohio. But pockets of skinhead subculture, which lends hate rock both its fan base and its talent pool, can be found all over the country. Page himself was from Colorado, and spent time playing music with white supremacist bands in Southern California and North Carolina.

Like the skinhead subculture itself, American hate rock is modeled after antecedents in England. In the 1980s, a British band called Skrewdriver released a series of albums that mixed punk rock with a call to arms for racially conscious Aryan warriors. Popular with both British and American skinheads, Skrewdriver songs like “Europe Awake (for the White Man’s Sake)” started being covered by American garage bands expressing the most rebellious of sentiments.

By the early 1990s, American skinheads had a slate of their own white power bands to express their sense of alienation in an increasingly multicultural nation. In 1993, George Burdi, lead singer of Rahowa (a skinhead slang abbreviation for “racial holy war”), started a music label called Resistance Records. Burdi, who has since renounced his racism, thus gave American hate rock its first viable business model, marketed as “the Soundtrack for White Revolution.” He also presided over the genre’s heyday, which roughly spanned the mid-90s. In its first three years of operation, Resistance was selling nearly 100,000 CDs and cassette tapes a year. Spurred by Burdi’s success, several record labels like Panzerfaust and Label 56 began to make the music available to the world via the largely anonymous marketplace of the internet. While skinhead bands sometimes struggled to find audiences in the U.S., they found legions of fans in Europe. The aftermath of the Cold War found many young Europeans clamoring for nationalism and an outlet for anti-immigrant hate, creating a concert market for American hate rock bands.

In musical terms, the central irony of hate rock is that it is fundamentally black music. Anchored in the 12-bar blues, the music of white supremacy is, formally speaking, a tribute to Chuck Berry as much as anything else. But such irony is lost on most hate rockers, or at least it’s beside the point. (Just try to explain to a neo-Nazi fan of Gaelic music that the Irish were not considered “white” a hundred years ago.) Their goal is simple: to express the alienation and frustration of straight white males who feel the loss of their special rights and privileges, using the most hyper-masculine, aggressive mode available to them.

Because they offer such a charged form of expression, hate rockers have served as a powerful recruiting tool for the white power movement. And in turn, the movement’s political organizations have provided some of the music’s major distribution channels. The genre has long been promoted by established white supremacist groups like Aryan Nations and the National Alliance. In 1999, the National Alliance purchased Resistance Records in an attempt to expand the reach of the label. These umbrella groups facilitated the sale of the music at rallies and marches, as well as T-shirts and publications, including Resistance, the Rolling Stone of the hate rock scene.

The good news is that, along with the broader white power subculture, the hate rock world seems to be collapsing in on itself. The 2002 death of William Pierce, head of the National Alliance, the 2004 death of Richard Butler, head of Aryan Nations, crippled the white supremacist infrastructure. Then in 2005, Anthony Pierpont, the founder of Panzerfaust Records and one of the biggest players in the hate rock scene, was drummed out of the racist movement when it was revealed that his mother was Mexican. Today bands generally resort to giving away their songs on platforms like MySpace.

The bad news, however, is that, in a subculture that thrives on heightening narratives of frustration and decline, further decline may only spur people like Wade Page to act on their hatreds.

On August 6, Label 56, the music label that sells hate rock by bands like Bound For Glory, Vinland Warriors, and Page’s group, End Apathy, issued a statement. It read:

Label 56 is very sorry to hear about the tragedy in Wisconsin and our thoughts are with the families and friends of those who are affected. We have worked hard over the years to promote a positive image and have posted many articles encouraging people to take a positive path in life, to abstain from drugs, alcohol, and just general behavior that can affect ones life negatively.

The statement went on to announce that all End Apathy images and products had been removed from the Label 56 website (although the End Apathy song “Greedy” was still on the label’s “Indie Music Sampler” for download). The label has sought to distance itself from the shooter. But this is a common tactic by hate groups when one of their members goes “rogue” and ends up in the media for committing some heinous crime. The white supremacist subculture whips its members into a frenzied state of paranoia, and then calls this a legitimate expression of white culture. Then, when someone starts acting out the subculture’s rhetoric, they deny playing any role in the mayhem.