Seanan McGuire seizes a cloud-blue My Little Pony figurine from among the dozens lined up behind her on her shelf. With a grin, the bestselling author explains that the animated series was a major influence on her work. My Little Pony was arguably the first longform fantasy aimed at girls, she says, a rainbow- and sparkle-laden portal fantasy with surprisingly grim plot twists incorporating evil witches, destructive demons, and the threat of wholesale armageddon looming over Equestria. My Little Pony routinely offered just the kind of hardcore twist readers have come to expect from McGuire’s novels, which often smoothly shift from an imaginative, humorous tone to one heavy with the threat of world apocalypse.

McGuire is talking over Skype just a few days before the annual Nebula Awards for science fiction and fantasy, which awarded her 2016 book Every Heart a Doorway its best novella prize. Every Heart a Doorway introduces us to a boarding school where children—mostly girls—are sent after they come home from visiting other worlds, fantastical places that slightly resemble Wonderland, Oz, or Narnia. When they return, changed by their experiences, Eleanor West’s School for Wayward Children helps them re-adjust to the normal world, as characters wrestle with the consequences of being torn from fantasy worlds.

It’s an unusual premise for a portal fantasy, since most tend to pick up when the hero either makes their home in the new world or returns back to Earth. Tweaking genre tropes, though, is business as usual for McGuire: Across nearly 40 books, McGuire—and Mira Grant, her pen name—has played with beloved genres (zombie apocalypse stories, whodunit crime thrillers, monster stories) to shed light on untold implications or unspoken assumptions in narrative archetypes.

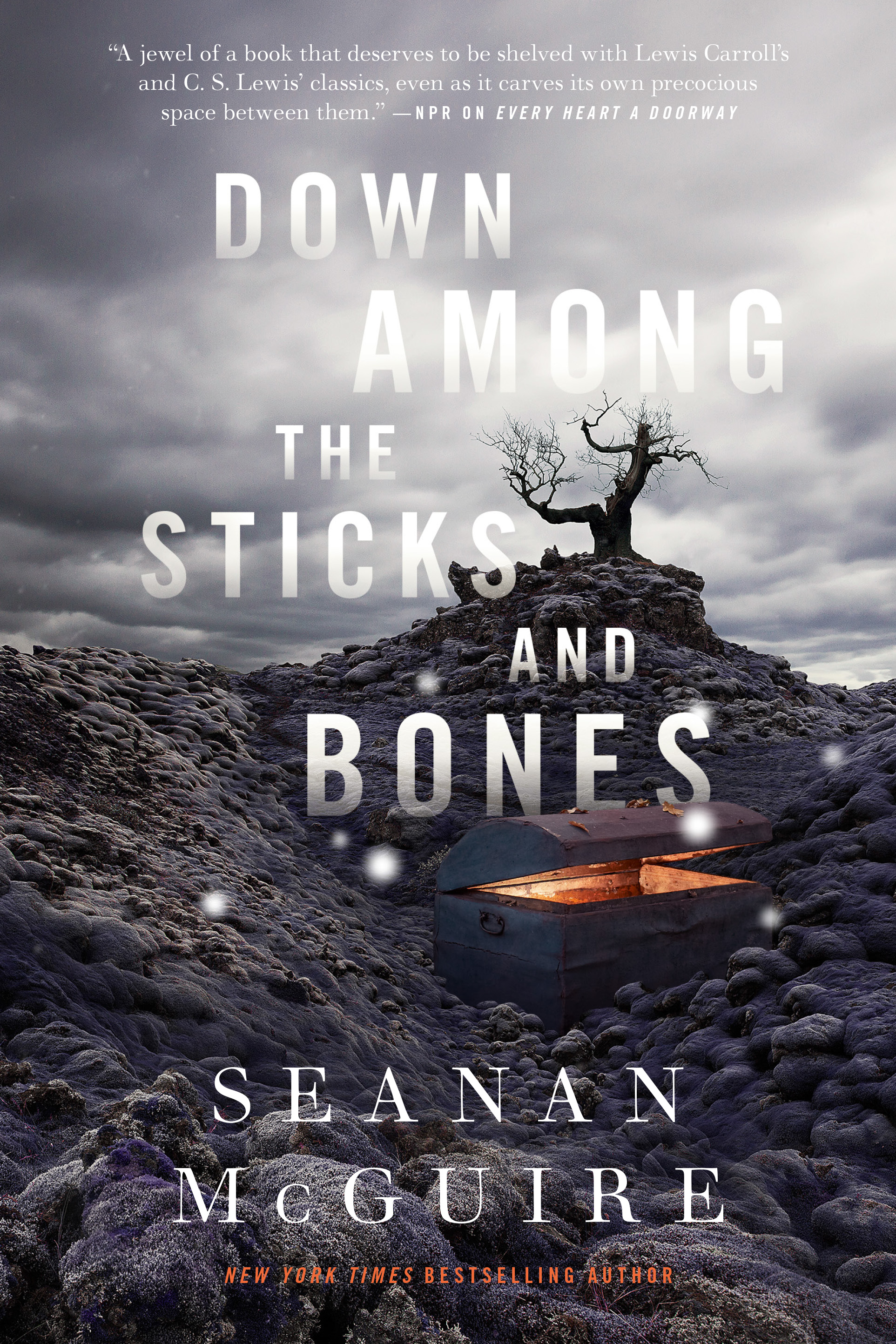

On Tuesday, the second novel in McGuire’s Wayward Children series, Down Among the Sticks and Bones, was released. Before its publication, Pacific Standard spoke to McGuire about her approach to expanding the possibilities for representation in fiction, her early exposure to portal fantasy, and her new books.

When you were a kid, what did you read, and what did you feel was missing in the fantasy that you consumed?

I grew up on welfare, which I bring up a lot because it’s really relevant to what I used to read. Growing up super poor, you read what your mom brings home because you can’t get anything else. My mother would come home from flea markets and yard sales with these gigantic boxes of whatever people were getting rid of. She was bringing books with unicorns and space ships on them for her nine-year-old, so I was getting science fiction that was 20 years out of date and I grew up on that.

There were virtually no women [in those books]. What I noticed was that only boys got to have adventures and go out and fight dragons or befriend dragons. Then a woman would show up and she would, 90 percent of the time, be a sexual reward for the guys for going out and having these adventures that were never offered to her in the first place. I didn’t want to sit at home and then have sex with the hero when he came back from going on this grand quest.

D&D [Dungeons & Dragons] and My Little Pony were my salvations because the original My Little Pony cartoon was hardcore epic fantasy that just happened to be about pink pastel horses that would burst randomly into song. With D&D I was allowed to play a female character, so I finally started seeing women having adventures.

Let’s draw a line from that girl consuming this media, realizing the absence of women, to who you are now. How do you address representational void in your writing?

I really like women. I really like girls. I really like hanging out with people who like telling their own stories. Even today, in a lot of media that’s written about a strong, female protagonist, most of the time she’s not allowed to have female friends. There’s still a very pervasive media idea that my existence is a competition for the attention and approval of men and that if I bring another woman into the story, suddenly she is competing with me for that attention. I try to make sure that all of my girls have friends. Or that, if they don’t, because not every character is super gregarious, that there’s actually a good reason.

(Photo: Tor.com)

It’s like the Rogue One phenomenon in which you have one strong, female central character but then basically everyone else in the whole movie is male.

Yeah. I really enjoyed the Ghostbusters reboot. I thought it was incredibly fun, [showing] comedians at the height of their strengths really having a good time. If you go back and watch the original Ghostbusters, they are men moving in a world of men. All of the extras are men, all of the secondary characters are men, you have Dana, and you have Janine, and that’s pretty much it for women. And both of them are very much stock characters. Watch the new Ghostbusters, and these are women moving in a world of men. All of the extras are still men. The crowd scenes are still predominately men.

How does your critique of representation in media play out when you write?

When I was working on my first trilogy as Mira Grant, a friend of mine said: “You know, I want to yell! I never get to see continental Indian characters in science fiction books. Science fiction casts are almost 90 percent white, with one or two people of color thrown in, then they claim they’re diverse.” That was a completely fair complaint. So I wrote him some [people of color]. Since then, I’ve kind of taken the policy of, every time someone comes up to me and says, “I don’t get to see my identity in these stories,” I make an effort to include someone [like] them.

I’m not saying we have to stop writing straight, white guys, I’m not saying we have to stop writing able-bodied characters, I’m not saying any of that. I’m saying, “If you have the flex, take the flex.”

If we publish that, you might going to get flooded with “Hey, do me!” requests.

I’ve been saying this, actually, at conventions and in public for ages. Someday I’d like to get to the point where no one is sending me those requests at all [because it’s all been done].

My lead [in Feedback] is an Irish expatriate lesbian who is in many ways the closest to a self-insert protagonist I have. I am of Irish descent, and I’m not a lesbian, but I’ve been in a committed relationship with a woman for 15 years, so a lot of what Ash does and says is filtered through how I would react to these things. Her girlfriend is Chinese American and is bisexual. She is in a green-card marriage with an African-American man named Ben and they have a gender-fluid fourth housemate who does make-up-review blogs and car-repair review blogs. All of these characters were, in some way, inspired by a real living person that I know. I’ve seen a couple of reviewers going, “I didn’t like Feedback because it felt like a diversity checklist.” And I’m kind of going like, “This feels like my D&D game [group, my real-world community], I mean, where are you that this is the diversity checklist for you?”

Why focus on the girls coming back to the “real world” in Every Heart a Doorway? Was part of your goal to create a predominately female and not particularly heteronormative or gender-normative environment? As well as, of course, writing highly entertaining portal fantasy?

Portal fantasy was the quickest way, and still is the quickest way, to get kids who are from this world fully immersed into a fantasy world because they get to learn the rules at the same time as the [readers]. The majority of the targets of classic portal fantasy, the ones that we actually focus on, the ones who make it home are girls. Wendy [in Peter Pan] spends her entire adventure trying to get back to home and domesticity and the chores she didn’t do and the responsibility she left behind—the boys say, “Screw this, I’m going to go fight pirates.” I think girls in classic portal literature are more likely to go and come back, boys either don’t go or don’t come back.

Next, you’re publishing a straightforward portal story with Down Among the Sticks and Bones.

Down Among the Sticks and Bones is basically about toxic gender roles. Let’s talk about how our parents make decisions about who we’re going to be without consulting us and what that does, and how much damage [that] does. It makes you who you are. Jack, who’s one of the two focal characters in Down Among the Sticks and Bones also has a form of obsessive compulsive disorder that is not quite identical to mine, but came on in a way very similar to mine in terms of how [her parents] ramped it up.

So, wait, you were an apprentice to a mad scientist?

No, no, I wish I had been. In this case, I knew that I needed to explain why [the twin sister protagonists] Jack and Jill were Jack and Jill. I wanted to actively show, here are these two little girls and here are their parents breaking them with a hammer and here they are trying to get out, because we don’t always give people credit for how much they’ve rebuilt themselves.

That’s pretty optimistic considering the grim plots your books follow, but I actually think giving people credit for re-invention is embedded in most of them.

Other than my vague desire to ignite the biosphere, I try to be fairly optimistic.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.