Every day, we’re seeing reports that consumers across the country will be dropped by their health insurance companies on January 1 or another date in 2014. But two central questions remain:

First, just how many people will be affected?

Second, and more importantly, is this a good or bad thing?

We don’t yet know the answer to either question, although the answer to the first question is surely a big number. Here’s where things stand:

A minimum of several hundred thousand people with individual health insurance policies (those not provided by their employers) have received letters notifying them that their coverage will be terminated on January 1—or at some date after that—because their plans don’t meet the requirements of the Affordable Care Act.

The issue has been percolating for several weeks, initially being overshadowed by the rocky rollout of the Healthcare.gov federal health insurance marketplace. But recently, in part because of a prominent NBC News report, the issue has gained traction. Republican lawmakers and the act’s opponents have given it more attention than the website’s continuing woes.

The story is full of nuance, and that’s what makes it easy to misunderstand.

What is definitely true is that many people are receiving notices saying that they will have to find new insurance coverage on January 1 or a later date. That directly contradicts what President Obama said repeatedly: that those who liked their plans could keep them. (The Washington Post has said Obama’s statements deserve four pinnochios because they were not true.)

How many people are affected?

According to the NBC News report:

Four sources deeply involved in the Affordable Care Act tell NBC News that 50 to 75 percent of the 14 million consumers who buy their insurance individually can expect to receive a “cancellation” letter or the equivalent over the next year because their existing policies don’t meet the standards mandated by the new health care law. One expert predicts that number could reach as high as 80 percent.

Sarah Kliff at the Washington Post writes:

It’s hard to put an exact number on this, given that insurance plans are the ones who decide whether or not to continue offering an insurance product. Experts have estimated that somewhere between half and three-quarters of those who currently buy their own policies will not have the option to renew coverage, which works out to around 7 to 12 million people.

Kaiser Health News, among the first to report on the issue, has been more conservative:

Health plans are sending hundreds of thousands of cancellation letters to people who buy their own coverage, frustrating some consumers who want to keep what they have and forcing others to buy more costly policies.

Kaiser posted more:

No one knows how many of the estimated 14 million people who buy their own insurance are getting such notices, but the numbers are substantial. Some insurers report discontinuing 20 percent of their individual business, while other insurers have notified up to 80 percent of policyholders that they will have to change plans.

Even when we do know a firm number, a more fundamental question is: Are these cancellations in consumers’ best interests?

In short, there are winners and there are losers—just as there have been in many other areas of the Affordable Care Act.

Some of the people being terminated from their plans will end up paying more for new coverage; some will pay less.

Some will qualify for government subsidies to lower the cost of their insurance even further, and some won’t.

In many if not all cases, they will receive a richer set of benefits. But many consumers may not have wanted them—or needed them (maternity care, for example).

Equally clear is that the new marketplace taking shape will not allow insurance companies to discriminate based on individuals’ pre-existing conditions; nor can insurers charge older people far higher rates than the young.

And just because somebody receives a cancellation notice and believes his or her insurance costs will go up doesn’t mean that’s right. Michael Hiltzik at the Los Angeles Times has done a good piece raising questions about the veracity of some of the stories being reported.

It’s easy to see this issue through a partisan lens, and that is happening. But then there are cases like Paul Levy’s.

Levy is a smart guy, the former president and CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and he has a pretty good understanding of how the health-care system operates.

Recently, he wrote a post on his blog (“Didn’t They Promise Lower Costs?”) about being dropped by his insurance company and being forced to spend considerably more money for insurance. He had purchased his policy after March 2010, so he wasn’t somebody covered by the president’s “keep your plan” pledge.

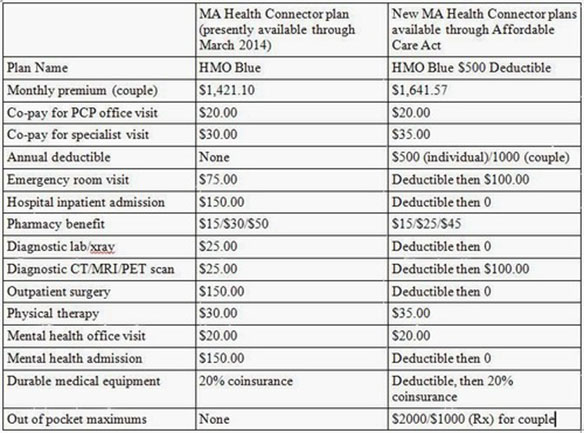

To summarize, for $600 more per month, my co-pay for almost everything goes up. My share of an inpatient admission or outpatient surgery goes up 233%; a CT or MRI goes up 500%; and ED visits are double the cost.

Now, I do get the benefit of an out-of-pocket maximum of $3,000. But I will pay $7,200 extra for that protection. To break even, I would have had to spend $10,200 in out-of-pocket items under the Massachusetts plan.

I know I could downgrade to a lower level of insurance and reduce my monthly premiums, but then other items would also change in price and availability. This is the plan that best meets our needs.

A professor of management and operations at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management followed up with Levy and suggested a different plan that could save him some money. But Levy still concluded he’ll be in worse shape than he is now. Here’s a graphic he made comparing his current plan with the plan he will purchase:

Levy writes:

My premium has gone up $220 per month (or 15%), and I will likely spend another $1000 covering the deductibles. My total percentage increase depends on how much additional care I need past my deductibles.

President Obama addressed the issue during a visit to Boston and made a pretty bold statement: “There are a number of Americans—fewer than five percent of Americans—who’ve got cut-rate plans that don’t offer real financial protection in the event of a serious illness or an accident. … A lot of people thought they were buying coverage, and it turned out not to be so good.”

Levy’s plan doesn’t appear to fit the president’s characterization. (Another example of sweeping generalizations dispensing with nuance.)

While Levy sees value in the act’s goals, he wrote that he wishes the administration was more forthright about what is actually happening and less defensive—for instance, parsing the words of the president’s pledge.

I have been listening to actuaries for many months who made it clear that the new plans would have to be more expensive to cover the law’s guaranteed issue and other insurance requirements. Those requirements are extremely desirable in providing insurability and financial security to millions of Americans and are, in fact, key attributes of the ACA. If the costs and benefits of these requirements had been addressed honestly by the administration, perhaps it would not feel the need to parse the President’s promise as finely as his spokesperson did today.

This post originally appeared onProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.